CRISPR trials yield encouraging data in blood disorders

Data on the first two patients to be treated with a CRISPR-based drug for the blood disorders beta thalassaemia and sickle cell disease suggest they can reduce symptoms.

The closely-watched trial of CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ gene-edited stem cell therapy – called CTX001 – is testing a one-off dose to see if it can reduce the need for blood transfusions and painful flares, and to make sure the treatment is safe.

The ex vivo approach involves harvesting patient’s blood stem cells, genetically modifying them with CTX001 to increase the production of a foetal form of haemoglobin normally switched off in adults – which provides protection from both thalassaemia and sickle cell. The modified cells are then reintroduced into the patient.

In time, the expectation is that CRISPR-based drugs may be used systemically to edit faulty genes in vivo, bypassing the cell harvesting and modification stage.

For now, the indirect approach seems to be working as hoped, with the infused cells engrafting into and repopulating the bone marrow.

Nine months after dosing, the thalassaemia patient has had no need for blood transfusions, a common requirement for people at the severe end of the disease spectrum.

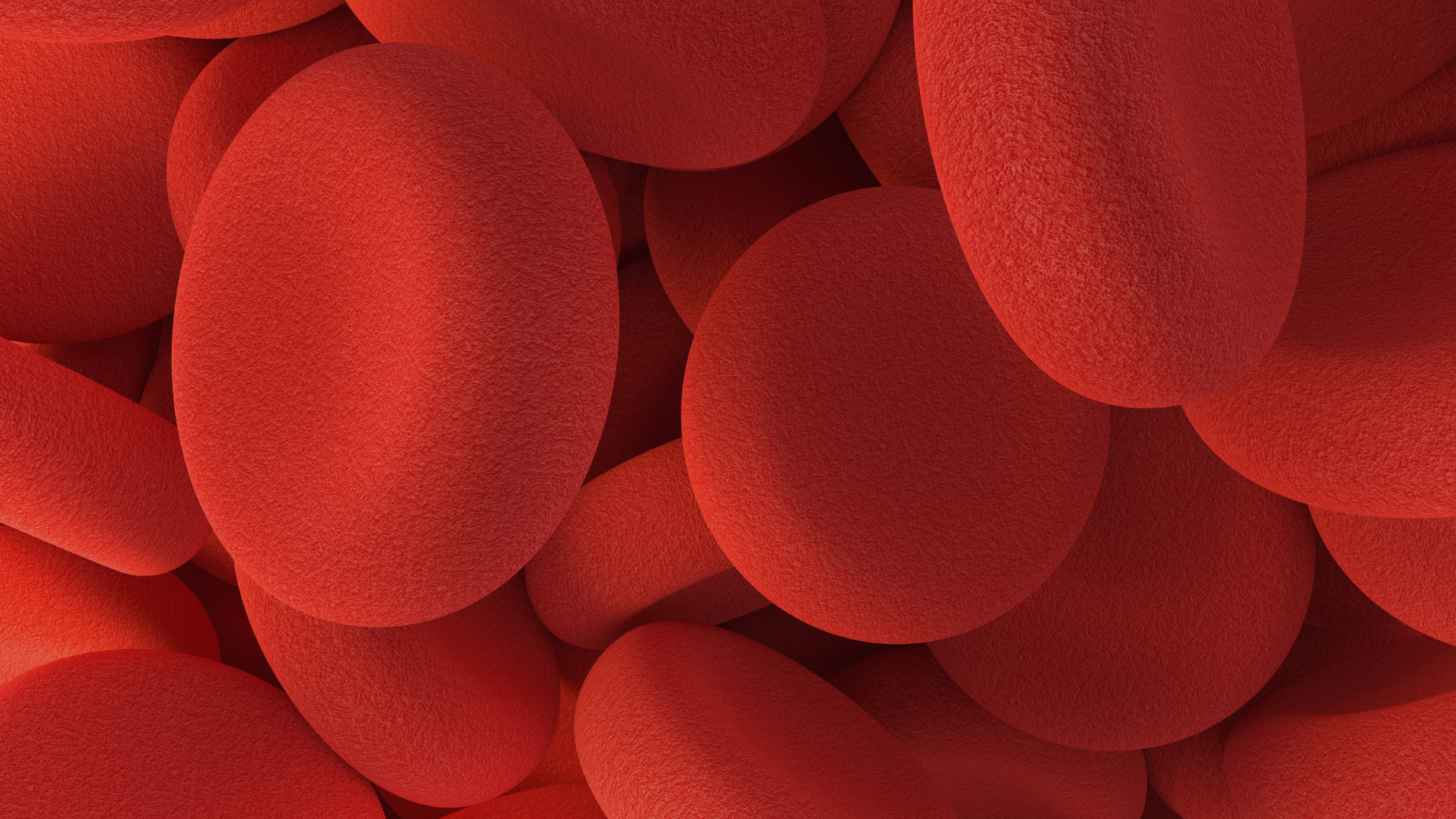

Meanwhile, the patient with sickle cell hasn’t suffered an attack – caused when defective red blood cells block blood vessels – in the four months since receiving the stem cells. Prior to the treatment they would generally have an attack every few weeks.

It’s clear that much longer follow-up and data from additional patients will be needed before a clearer picture of efficacy can be drawn, but the results point to proof-of-concept at the very least, with haemoglobin levels rising in both patients to near-normal levels.

There are also still questions about the safety of the cell therapy procedure, which involves a ‘conditioning regimen’ based on the chemotherapy agent busulfan to destroy the patients bone marrow before the modified stem cells are administered.

Looking at the safety data, the thalassaemia patient developed pneumonia and liver disease after the treatment, while the sickle cell patient developed sepsis, gallstones and abdominal pain.

None of the side effects were thought to be linked directly to CTX001 itself, according to the two companies, but the induction regimen still makes the treatment challenging.

The potential pay-off could be freedom from transfusions and sickle cell attacks that would transform the quality of life for patients with the conditions.

Both thalassaemia and sickle cell trials will eventually enrol around 45 patients apiece, who will be followed for two years after CTX001 dosing.

CRISPR and Vertex began a strategic research collaboration in 2015 to discover and develop gene editing treatments using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to correct defects in genes known to cause or contribute to certain diseases.

Their initial results come after a one-shot ex vivo gene therapy for beta thalassaemia – bluebird bio’s Zynteglo – was approved in Europe in June with a list price of €1.58 million (around $1.77 million) over five years.

That therapy is based on stem cells taken from patients that are genetically modified to contain a working gene for beta-globin, a haemoglobin component that is deficient in thalassaemia patients. It is due for US approval next year and is also in late-stage development for sickle cell.

There’s been more good news for the sickle cell community of late as well. Last week, Novartis claimed an FDA approval for Adakveo (crizanlizumab), an antibody therapy for preventing sickle cell attacks.