Medical affairs: learning to change behaviour?

Brian Jepson reviews recent research that points to the need for greater engagement with behavioural science among medical affairs professionals, to inform medical education and engage HCPs.

Application of behavioural science to medical education and other healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) engagement activities lags behind many other areas in healthcare, despite the huge opportunity to benefit patient care. There is a clear need for medical affairs (MA) roles to be more engaged in behavioural science approaches, and for a better understanding of how they can be applied, in an ethical and compliant way, to medical education, to encourage positive behaviour change among HCPs, according the results of recent research.

We joined forces with pharmaphorum media to conduct extensive research among more than 160 senior pharmaceutical industry executives and globally-renowned academics to identify the level of understanding, adoption and application of behavioural science in healthcare.1 There was remarkable agreement, with 98% of respondents endorsing the importance of behavioural science to the future of healthcare.

However, there were very different perspectives on the role of behavioural science in different disciplines and activities, and we were particularly interested to understand how behavioural science is shaping medical communications activities driven by MA teams.

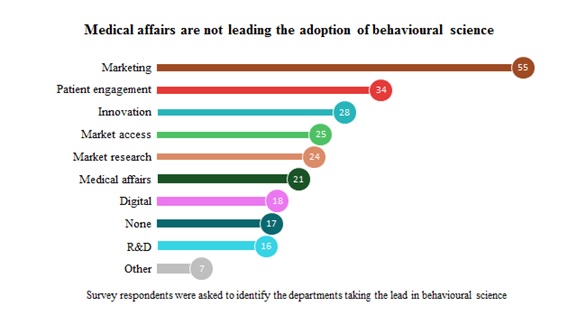

Medical affairs: under-used stakeholder in behavioural science

MA teams are playing an increasingly pivotal role in communications, especially with the separation of scientific and promotional education.2,3 Despite this, they are not leaders in adopting behavioural science, missing a huge opportunity to improve educational and clinical programmes to enhance patient care.

MA was ranked in only sixth place, which is a surprise considering that some of the activities it leads (eg physician communication) were ranked highly in terms of their relevance to the application of behavioural science. Marketing and patient engagement were the key functions believed to have the biggest roles in applying behavioural science. Why is this? Do people associate the application of behavioural science with patient adherence programmes and ‘marketing and influence’, rather than communication of medical content? Do those with a more traditional scientific background see behavioural science as a ‘soft science’ that lacks credibility? Why is medical writing not considered more applicable to behavioural science techniques when it’s a key component of the majority of medical education activities?

The key learning is that we must forge a greater recognition of the relevance and benefit of behavioural science in the effective communication of medical content – that this is based on a solid scientific foundation, can be achieved ethically and is aligned with the culture and values of MA teams.

Behavioural science can transform the effectiveness of medical education programmes

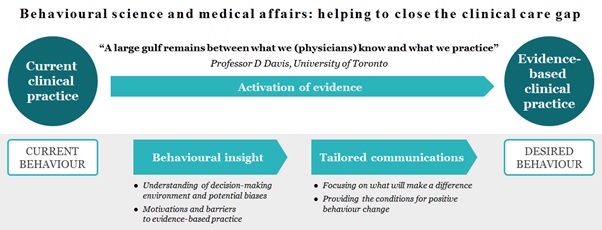

So what is the benefit for MA teams? One key area is evidence-based communications to support improvements in clinical practice, but the biggest barrier to this happening in the real world is behaviour. We all make irrational decisions, and HCPs are no exception – drugs proven to be cost-effective by high-quality research4 are often not used routinely in the real world.5,6 So, if we are to develop truly effective communications, we need to base these on an understanding of human behaviour, the decision-making environment and potential biases that compromise evidence-based medicine. With this insight we can tailor communications to ensure clinical evidence is translated into practice and that patients reap the rewards.

The potential of behavioural science to improve clinical outcomes through medical education is illustrated by an award-winning disease education programme on an ultra-rare disease, which, if left undiagnosed, can be fatal.7 Behavioural insight into the target audience, many of whom had never encountered this rare disease, showed that concise and targeted communications, easy-to-use tools, longitudinal programmes and peer-to-peer sharing of clinical experience were likely to be effective. We applied these principles to develop the programme, which increased the awareness and diagnosis of this serious, ultra-rare disease.

‘We all make irrational decisions, and HCPs are no exception’

The challenge: from recognition to adoption

How do we address the perception that behavioural science is used by marketers to manipulate customers and is not appropriate in a clinical or scientific setting? Fortunately, behavioural science has been widely researched and has a strong foundation of nearly 60 years of scientific study.8 Based on these principles, we know that when we use the right language and activities in our education programmes, we are more likely to enable behaviour change and drive more rapid adoption of evidence-based medical practice.

‘We must clearly explain the benefits of behavioural science and back them up with scientific evidence and metrics to demonstrate the importance of embedding them in communication programmes’

We have the evidence base for behavioural science, so the opportunity for medical affairs teams is to incorporate this approach into their practice. A key part of this opportunity is to address the perceptions of manipulation, by framing the overall intention as facilitating the pathway to evidence-based best practice, using scientific language and values, and rigour in measuring outcomes. Expert partners, such as communications agencies with hands-on experience of applying behavioural science, have a key role to play in both championing the approach and supporting skills development. In much the same way as medical affairs teams have championed ethical and evidence-based scientific communications, they have the opportunity to lead the ethical and compliant application of behavioural science to improve the effectiveness of these communications.

We all follow well-established human behaviour; understanding how this can impact on clinical decision making enables development of smarter communications that support evidence-based clinical practice and improve patients’ lives.

References

- James C. New research: can pharma get healthy rewards for good behaviour? pharmaphorum 2017. (last accessed 5 October 2017).

- Pisani J, Lee M. A critical makeover for pharmaceutical companies: overcoming industry obstacles with a cross-functional strategy. Strategy& 2017. (last accessed 5 October 2017).

- Plantevin L, et al. Reinventing the role of medical affairs. Bain & Company 2017. (last accessed 5 October 2017).

- Haines A, et al. Bridging the implementation gap between knowledge and action for health. Bull World Health Organ 2004; 82: 724-731; discussion 732.

- Johnson M J, May C R. Promoting professional behaviour change in healthcare: what interventions work, and why? A theory-led overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008592.

- Dombrowski SU, et al. Interventions for sustained healthcare professional behaviour change: a protocol for an overview of reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 173.

- Picken L. Horses or zebras: inspiring behavioural change to make the rare recognised. pharmaphorum 2017. (last accessed 5 October 2017).

- Miller J G. Toward a general theory for the behavioral sciences. Am Psychol 1955; 10: 513-531.

About the author:

Brian Jepson, PhD, is a Scientific Director at Complete HealthVizion, a McCann Health company. He is an expert in understanding how science can be translated into medical education programmes that improve patients’ lives.

Read more from Complete HealthVizion:

Bringing behavioural science to medical education: a transformative combination?

Horses or zebras: inspiring behavioural change to make the rare recognised