AI medicines are coming: Building the foundations for discovery’s next era

Drug discovery has always been a slow business. Ideas spark quickly, but turning them into safe and effective treatments takes years – often more than a decade. The journey is expensive, risky, and uncertain, with the majority of candidates falling away long before they reach patients.

Artificial intelligence is beginning to change that. It isn’t a silver bullet, and no medicine yet on the market has been “discovered by AI” alone. But the technology is already reshaping how scientists work – from the questions they ask in the lab to the way clinical trials are designed. Its influence is becoming harder to miss.

That progress has taken time. As Elena Fonfria, director and project leader of biology at Recursion, puts it: “Biology is really complex and drug discovery is becoming slower and more expensive to just explore every single avenue or try to understand everything. What we do is use AI and technology to have a fundamentally new approach for the model that vastly improves speed and efficiency.”

For years, that foundation didn't exist. Today it does. And that makes all the difference.

Building a better starting point

Drug discovery has always depended on data. The problem was scale. Scientists could hypothesise and test thousands of compounds in the lab, but biology contains millions of possible interactions. For Lina Nilsson, chief platform officer at Recursion, the bottleneck in the industry has long been the absence of high-quality, reliable datasets suitable for machine learning.

"The bottleneck, the foundation of doing good machine learning, is having data that you trust," she explains. "You need data that's reliable and real in order to build great models."

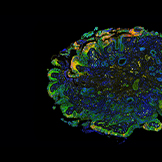

Recursion has spent more than a decade building this foundation. The company’s phenomics and transcriptomics platforms provide complementary views into human biology: microscopy imaging that captures the broad activity across cells, and molecular data that tracks how DNA is transcribed into proteins. Together, these assays are run at an industrial scale, producing almost 20 petabytes of data.

“Phenomics gives you a view of the broad activity across a cell,” Nilsson says. “Transcriptomics clicks down into another view of the central dogma […] They’re both assays you can run at really high control and repeatability, with fit-for-machine-learning controls in order to build these models.”

She continues: “This makes things way more efficient because, rather than having to generate data every time you want a new insight, you're relying on the data you've generated previously over time. And because of the reliability of the data, the way these machine learning models work, every time you add a data point you're able to compare it against large swaths of existing data.”

The numbers are staggering. Millions of experiments can now be run under tightly controlled conditions. Petabytes of results are stored and analysed. What matters is not just volume, but repeatability. The same signal can be observed week after week, or known drug interactions show up exactly as expected. That reliability turns raw biology into something AI can truly learn from.

Computation is the other critical ingredient. Supercomputers now simulate aspects of human biology digitally, creating “world models” that don’t just describe cells, but predict how they might behave under different conditions. For Nilsson, this marks a turning point: “In this new era of foundation models and world models, that’s a big differentiator.”

A faster way to learn

If better data is the starting point, speed is the next advantage. Fonfria explains: “It’s not introducing more complexity, but trying to decode biology to improve patients’ lives.”

Traditionally, scientists might screen half a million compounds in search of a lead. AI changes that process. Models generate predictions about which molecules could work, and those predictions are then tested in the lab. Results feed back into the system, sharpening the next set of ideas. Fonfria calls it the “predict-test-learn” cycle. It means fewer dead ends, less wasted time, and the chance to move quickly when a promising signal appears.

“In chemistry, you would need a very good chemist to explore all the chemical space – the computers can imagine the molecules automatically,” she explains.

"AI is very fast and very efficient in pinpointing, once we define the project. The computer doesn't get tired. The computer is not biased."

This approach is already visible in pipeline projects. In oncology, AI has guided the design of CDK7 inhibitors and uncovered new biology around RBM39. In rare diseases, it has pointed researchers towards alternative strategies for conditions like hypophosphatasia – ideas that would have taken far longer to surface using conventional methods.

The same principle applies in clinical development. Predictive models suggest the most appropriate doses, simulate patient responses, and highlight where to find eligible participants. The effect is shorter trials and fewer burdens on patients. As Fonfria explains: “If we are sure in our predictions, if we are anchoring what we know preclinically, and our models, that means that very quickly we can give the patients doses that will be appropriate for them. Collectively, the clinical trials are shorter and better targeted for what the patient needs.”

Looking back to look forward

AI isn’t the first technology to promise a revolution in discovery. Genomics was expected to unlock a flood of new cures. Combinatorial chemistry promised millions of molecules on demand. Computational chemistry was meant to predict drug behaviour with precision.

Founding fellow at Recursion Mike Genin, who has spent more than 30 years in discovery roles primarily at large pharma companies, has seen each of these waves rise and fall.

“I’ve never seen anything live up to its initial hype, ever […] Not even genomics,” he says. “It's because it's so hard, it's so complex, and nobody ever really tried to put all the pieces of the puzzle together. There are a variety of reasons for that. I think part of the reason is we didn't have the computing power that we have now.”

So, why does he believe AI is different? Because, this time, the advances are happening together. Reliable data. High-throughput automation. Generative chemistry. Supercomputing. Instead of sitting in silos, these tools are converging.

"Now, we’re at a point in time where if we do it right, we have the ability to realise some of that promise," he says.

Progress has still required patience. Nilsson remembers when some of the approaches that now deliver results were little more than cartoon diagrams on a PowerPoint slide. Early attempts failed. But coming back to the same ideas with better tools has made a difference: “There are definitely models that we tried years ago, and then we’ve come back on and had success more recently,” she recalls.

“A decade ago, most companies, including Recursion, were building models off of single datasets,” she explains. “Now, we're seeing huge improvements in performance and their ability to understand biology and chemistry by combining different datasets.

“That's because the models aren't just learning about one assay, they're learning to reason about biology and chemistry broadly. That's really new.”

Keeping patients in focus

For all the technical detail, the drive behind AI in drug discovery is ultimately human. Genin’s perspective is shaped by his own cancer diagnosis as a teenager and later the loss of his mother. “Loving someone who has a devastating condition is by far worse than having that condition yourself,” he reflects.

That experience left him determined to pursue not incremental improvements, but transformative therapies. After decades in big pharma, he believes AI may finally deliver the step change patients need.

“I first had cancer in 1980. The field has certainly changed since then, but it has not changed enough. The drugs they gave me back in 1980, they still use today, which is good. It shows they work at times, but they're actually pretty toxic agents, as are most chemotherapeutic agents,” he says. “Rather than working on best-in-class molecules, I was always interested in first-in-class molecules, taking advantage of novel biology, novel pathways that nobody's ever done before. I thought, and believe to this day, that's where real effective additions to the current arsenal of therapies will be discovered.”

Fonfria sees the same urgency: “Patients cannot wait.” For her, the potential of AI is not just efficiency, but disruption – offering new approaches to diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s, where existing treatments remain limited. “The big diseases don’t have a proper cure, yet […] Getting the computers to assist us, I think it’s a brilliant approach. It’s really exciting.”

Nilsson adds that culture matters as much as code. The ability to bring biologists, chemists, engineers, and data scientists together is what unlocks breakthroughs. “It’s not a specific model, it’s not a specific dataset. It’s how you make these teams that come from different worlds and disciplines able to communicate and work closely,” she says.

New discoveries on the horizon

The first medicines shaped by AI will likely emerge from pipelines where machine learning has played a role at multiple stages: identifying targets, designing molecules, predicting toxicity, and guiding trials. AI won’t replace scientists, but it will change how they work and what they can see.

For Genin, the test of success will always come back to the clinic. “Efficiency, in my mind, is speed and quality. If you’re sacrificing quality, then I’m not interested. Quality at the end of the day is what moves the needle in the clinic, and it’s what gives parents and patients hope.”

AI is no longer just a distant promise. It is already part of how scientists discover and test new medicines, and the first generation of therapies shaped by it is edging closer. Progress has taken time, as it always does in science, but the direction is clear.

While the near-term breakthroughs may not wear the badge of “AI drug” yet, their origins will be inseparable from the models and algorithms that guided their discovery. And, for patients waiting on better options, that shift cannot come soon enough.

About Recursion

Recursion (NASDAQ: RXRX) is a clinical stage TechBio company leading the space by decoding biology to radically improve lives. Enabling its mission is the Recursion OS, a platform built across diverse technologies that continuously generate one of the world’s largest proprietary biological and chemical datasets. Recursion leverages sophisticated machine-learning algorithms to distil from its dataset a collection of trillions of searchable relationships across biology and chemistry unconstrained by human bias. By commanding massive experimental scale – up to millions of wet lab experiments weekly – and massive computational scale – owning and operating one of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, Recursion is uniting technology, biology and chemistry to advance the future of medicine. Recursion is headquartered in Salt Lake City and has offices in Toronto, Montréal, New York, London, Oxford area, and the San Francisco Bay area.

Learn more at www.Recursion.com, or connect on X (formerly Twitter) and LinkedIn.

About the interviewees

Lina Nilsson is the chief platform officer of Recursion, driving ongoing advances to the Recursion OS, an AI-driven end-to-end platform combining 65+ petabytes of proprietary data, machine learning foundation models, and industry-leading compute.

Previously, she was the COO of Enlitic, a biotech startup that develops deep learning solutions to improve clinical radiology. As Innovation Director at University of California, Berkeley, she helped spin out social-impact technologies and develop entrepreneurial programmes for students. She conceptualised and helped launch HardwareX, a peer-reviewed journal for open-source hardware that is hosted by Elsevier. Nilsson has been recognised on MIT Technology Review’s “TR35” annual list of the world’s top innovators. Her writings on open science, social impact technologies, and gender & tech have been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Science, and Make Magazine.

Mike Genin is a founding fellow at Recursion where over more than seven years he has been a key leader shaping and building out small molecule drug discovery in Recursion’s TechBio paradigm. Prior to Recursion he spent 25+ years in big pharma working with world-class discovery groups at Upjohn/Pharmacia/Pfizer, Marion Merrell Dow/Aventis, and Eli Lilly where he advanced projects in infectious diseases, cardiovascular & metabolic diseases, and immunology therapeutic areas. He has a passion for exploiting cutting edge technology to accelerate the discovery and development of new disease modifying agents for patients and those who care for them.

Elena Fonfria is the director and project leader of Biology at Recursion. She’s an experienced R&D drug hunter in the field of in vitro pharmacology and cell biology, with 26 peer-review publications, three patents and over 20 years of industry experience in pharma and biotech, including at GlaxoSmithKline and Ipsen. She is passionate about bringing ideas from inception to clinical candidate stage, and has a strong track record in doing so for both small molecules and biologicals.

Supercharge your pharma insights: Sign up to pharmaphorum's newsletter for daily updates, weekly roundups, and in-depth analysis across all industry sectors.

Want to go deeper?

Continue your journey with these related reads from across pharmaphorum

Click on either of the images below for more articles from this edition of Deep Dive: AI 2025