Real-world or real evidence?

There was a time when the distinction between data from clinical trials and data from any other source was clear. Clinical trials created clinical evidence to determine regulatory decisions and guide clinical practice; whereas all other data was of second tier being used by commercial teams to improve market access. Like the aristocrat and the road sweeper – the two data sets rarely crossed paths.

Then came real-world data (RWD), who’s initial entrance was less of a revolution, and more of splinter group promising to change the world for the better. Like many newcomers, its first challenge was to define what real-world data is, with most settling on a definition that says RWD is the product of routine clinical practice rather than a formal trial. Usually this is aggregated electronic health record (EHR) or insurance claims data, but it could also include data routinely collected from apps and wearables. Yet as we will see, this description is becoming obsolete as the line between clinical trials, clinical evidence and RWD blurs.

So, is the revolution really coming? This article will seek to answer this by exploring the underlying drivers such as the maturity of electronic health records and the shifting regulatory environment. It will also examine some of the companies who are betting big that now is the time for true change in evidence creation.

Getting comfy with RWD

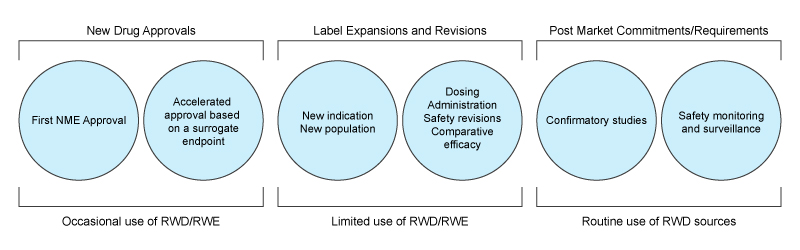

The classic comfort zone for RWD is safety monitoring, as well as Health Economic Outcome Research (HEOR) that provides important post-market information for making healthcare coverage and access decisions. These uses are now well-established, with the FDA Sentinel initiative in the US being perhaps the most well-known example of safety monitoring, and big CRO having well-established RWD products that support market access through a variety of retrospective analyses. So why is it that RWD has been focussed on these use cases rather than replacing expensive clinical studies? Diving into this question reveals some important insights to the limitations of this type of data.

Achilles heal

By definition, anonymisation or even pseudonymisation places fundamental limitations on the value that can be derived from real-world data. Yet, this is a necessary step as most circumstances require the removal of patient identifiers when aggregating data to comply with GDPR & HIPPA in the US. This means that without a significant manual process at the site where the data has been sourced, investigators are unable to:

- Consent subjects – Secondary use of health data that has been pseudonymised does not require consent in many cases. However, if it is being used to build regulatory grade evidence many sponsors insist on a consent as best practice.

- Augment data fields – Both practically and legally it becomes difficult to link aggregated pseudonymised data to any other data. So you are stuck with what you have, which is unlikely to include all the fields required to create robust evidence.

- Query inconsistencies – With no scalable mechanism to query the source of the data – which may be the treating clinician or the patient – investigators are unable to stand behind conclusions derived from RWD in the same way as a traditional prospective study.

- Randomise – You can’t randomise retrospective data, and no tech or AI can overcome this. For regulators, it seems the jury is still out to decide if and when retrospective analyses can be used in place of prospective randomised controlled trials. The FDA and EMA have indicated there may be some circumstances where real world data can be used to support decisions on clinical efficacy but the truism still stands that only randomisation can establish causality.

Janet Woodcock, director of the US Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), summarised these points well at a conference in March 2016 where she joked: "Data gathered from healthcare has always had one characteristic: it's not very good."

She added: "The question is can we randomise people within the healthcare system to do a trial inside the healthcare system utilising the data collection methods of the healthcare system?"

Where next?

In spite of these limitations there is huge promise with established players and start-ups alike who see opportunity to use RWD to reverse the escalating inefficiencies in evidence creation. At a macro level it is possible to think of these organisations in two groups; one group views health data as the asset, and the other who use health data as a means to drive efficiency in the process of evidence creation.

Data as the asset

This broadly covers organisations that aggregate pseudonymised data, then apply data science to extract real-world evidence. Included in this group is Aetion who are headquartered in NY and recently raised a further $22 million in funding, and has attracted high profile board members such as the former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb. Their aim is to extend the reach of real world analyses into regulatory grade evidence creation with some success in duplicating RCT results using real-world analysis. However, as the FDA themselves point out, Aetion will need to demonstrate a large number of examples where RCT results correlate to their analyses before they will routinely accept these in place of prospective studies.

TrinetX recently acquired Custodix to expand their data network into Europe, and in doing so established themselves as a major global player in the real-world market. In their early days, TrinetX were focussed less on RWE and more on trial optimisation through using their data to improve study feasibility analysis and recruitment. However, as a data aggregator they rely on the source site to reidentify and engage the patients so a natural path was for them to expand into real-world analyses with recent publications in focussed on cardiovascular outcomes.

Data as a tool

Other organisations are approaching this from a different angle using real world data including integrations with site EHRs and remote monitoring to drive efficiencies across the study lifecycle. Castor is an electronic data capture system that is able to map data from certain electronic record systems such as EPIC and Cerner to reduce the manual process of transcribing data into the case report form. Castor and other EDC platforms have also built in patient facing apps that create customisable patient report forms that can be remotely completed, further reducing the cost and time at the site. Others such as Science37 can even integrate wearables into prospective trials to create fully remote direct to patient studies using Science37 ‘metasites’ rather than bricks and mortar locations.

Why now?

So why is it that the last five years has seen such growth in interest of real-world data? Two of the key drivers include the improved interoperability of health records and the complimentary legislation brought in to drive trial innovation in the US. The Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) API standard is now being adopted wholesale across much of the global EHR market, and whilst FHIR doesn’t solve issues such as data quality it does make 3rd party integration substantially more straightforward. The 21st Century Cures signed into law in December 2016 aims to expedite the process of drug development including mandating the FDA to undertake an evaluation of real-world evidence in regulatory decisions. This combination has created both the opportunity and the top down advocacy to unlock a wealth of innovation from both public and private sectors.

Here to stay

Whilst there are many unanswered questions – not least those around patient rights around secondary use of health records which we have not addressed in this article – one thing is clear: real world data is here to stay. Moreover, its expanded mandate propelled by the maturity of health records and a number of plucky startups will see it reaching parts of the clinical evidence hierarchy thought untouchable just a few years ago.

About the author

Dr Matt Wilson is a clinician, academic, and CEO of the research platform uMed. uMed is a technology enabled site network that links health data to real-time patient engagement.