A history of vaccination: How immunisation transformed public health

The history of vaccination is a story of scientific ingenuity, medical breakthroughs, and public health triumphs. From its earliest roots in the late 18th Century to the rapid advances of the 21st, vaccines have saved millions of lives and reshaped our approach to disease prevention. The journey has been marked by major milestones – some celebrated, some controversial – but all crucial in the fight against infectious diseases.

At a time when vaccines have come under heavy scrutiny from public officials, we are taking their advice, following the science to examine key moments in vaccine history, tracing their development, impact, and the cultural and scientific shifts that accompanied them.

1700s

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Edward Jenner, and the first smallpox vaccine

Before vaccination, smallpox was one of the deadliest diseases in human history, with mortality rates as high as 30%. Variolation – the practice of deliberately infecting someone with a mild case of smallpox – had been used in parts of Asia and the Middle East for centuries, but it carried significant risks.

Image: Lady Montagu in Turkish dress.by Jean-Étienne Liotard. Credit: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons,

Having observed the practice firsthand while living in Turkey, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu – a smallpox survivor herself – returned to England to find the country battling a smallpox epidemic. Concerned for her child, she quickly asked the embassy doctor to perform variolation on her young daughter. Though hesitant, he acquiesced, and in April 1721, Mary Alice became the first to receive the procedure in Britain. However, while successful, Lady Montagu's push for inoculation was publicly dismissed by 18th Century society as the idea of an "ignorant woman".

Across the Atlantic, enslaved people had brought the concept of variolation to the American colonies. So, when smallpox raged through the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, George Washington, as commander-in-chief, made the controversial move to mandate smallpox inoculation for soldiers who lacked immunity. It was the first medical mandate in American history.

"This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust in its consequences will have the most happy effects," he wrote of the effort.

Image: Portrait of Edward Jenner by John Raphael Smith. Credit: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

More than half a decade later, in 1796, English physician Edward Jenner observed that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox seemed immune to smallpox. As such, he hypothesised that exposure to cowpox could protect against the deadlier disease.

To test his theory, Jenner injected an eight-year-old boy, James Phipps, with material taken from a milkmaid's cowpox sore. While Phipps did end up developing cowpox, when later exposed to smallpox, the boy showed no symptoms. Jenner's findings led to the first formalised vaccine, laying the foundation for immunology. Despite initial scepticism – and fears that the inoculation would turn people into cows – his work gained acceptance, and smallpox vaccination spread across Europe and beyond. This discovery was the first step toward the eventual eradication of smallpox nearly two centuries later.

1880s-1890s

Louis Pasteur and the rise of attenuated vaccines

While Jenner's work proved the concept of vaccination, it wasn't until the late 19th Century that scientists began to understand how weakened pathogens could be used to stimulate immunity.

Almost a century after Jenners revealed his smallpox findings, famed French chemist Louis Pasteur – already established as a pioneer in microbiology and bacteriology – theorised that vaccines could be developed for a wider range of deadly diseases.

His first breakthrough began in 1879, when he and his assistant, Charles Chamberland, were researching chicken cholera. In a serendipitous event, Chamberland forgot to inject their chicken subjects with fresh cultures of the viral bacteria before going on holiday. When he returned to the lab weeks later, Chamberland injected the chickens with bacteria from the now month-old samples. To his surprise, the inoculated chickens developed mild symptoms, but recovered fully. This accidental discovery led to the first laboratory-developed vaccine.

Buoyed by this success, Pasteur then turned his focus to anthrax, developing a vaccine in 1881 by exposing the bacterium to oxygen, weakening it enough to induce immunity without causing disease. This demonstrated that artificially weakened (attenuated) pathogens could be used for vaccines.

Image source: Portrait of Louis Pasteur by Albert Edelfelt. Credit: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Pasteur's most famous work followed in 1885 – the rabies vaccine. Using dried spinal cords from infected rabbits, he weakened the virus for safe human use. His first patient, nine-year-old Joseph Meister, had been bitten by a rabid dog. It was a very risky move for both patient and researcher – Pasteur was not a medical doctor, he had never successfully used the vaccine on a human test subject, and he could face severe repercussions if the procedure went wrong. On the other hand, without treatment, the boy would have faced certain death.

Thankfully, the vaccine saved Meister's life, proving that immunisation could be used both preventatively and as a post-exposure treatment. Pasteur's work laid the foundation for future vaccines and led to the founding of the first Pasteur Institute in 1888.

As vaccines proved their effectiveness, countries around the world began adopting immunisation programmes. Governments and scientists worked together to mass-produce vaccines, with advances in bacteriology and immunology accelerating development. The 19th Century also saw the rise of public health institutions, which played a vital role in distributing vaccines and educating the public about their benefits.

1920s-1940s

Early mass vaccination efforts

The 1920s saw key breakthroughs in vaccine technology, including the discovery of toxoid vaccines for diphtheria and tetanus. Scientists learned that bacterial toxins could be neutralised while still prompting an immune response. This innovation led to the first diphtheria vaccine and the later combination of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) into the DTP vaccine by the 1940s, marking one of the first multivalent vaccines – where protection against multiple diseases is provided in a single shot.

During this time, tuberculosis remained a major global killer. By the late 19th Century, 70–90% of the urban populations of Europe and North America were infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and about 80% of those who developed active TB died from it. The BCG vaccine, developed in 1921 by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin, provided some protection and became widely administered in high-risk areas. The League of Nations adopted the BCG vaccine as a recommended tuberculosis vaccine in 1928, though widespread use did not occur until after World War II.

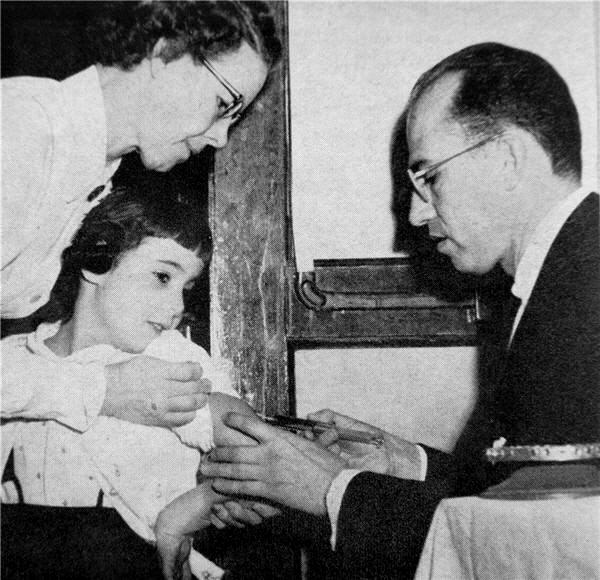

Image source: Dr. Jonas E. Salk (right) administering an inoculation. Credit: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Wartime efforts in the 1940s also accelerated vaccine production. With soldiers at risk of typhoid, tetanus, and influenza, large-scale immunisation campaigns were launched. The first influenza vaccine was approved for military use in the United States in 1945 and civilian use in 1946, following research by Thomas Francis Jr and American virologist Jonas Salk. Influenza vaccine development was prioritised due to the devastating impact of the 1918 pandemic.

At the close of the 19th Century, yellow fever was one of the most feared diseases in the Western Hemisphere and West Africa. In the 1930s, virologist Max Theiler developed the first effective yellow fever vaccine by repeatedly passing the virus through minced chicken embryos, reducing its neurovirulence. The vaccine was first tested in Brazil in 1938 and proved highly effective. More than 400 million doses have since been administered over 60 years, and the vaccine remains a critical tool for controlling outbreaks.

Following World War II, vaccine distribution improved globally. With medical advancements and government-funded programmes, childhood vaccination schedules were established, leading to the near-eradication of diseases like measles, mumps, and rubella. Widespread immunisation helped reduce mortality rates and increased life expectancy across nations.

1950s-1960s

The Polio epidemic and the race for a vaccine

Polio was one of the most feared diseases of the 20th Century, paralysing and killing thousands each year. In 1955, Jonas Salk introduced the first polio vaccine, using an inactivated (killed) virus to stimulate immunity. Administered via injection, the Salk vaccine led to a dramatic decline in cases. The Vaccine Advisory Committee approved a field test of Salk's polio vaccine, and the trial began the next day, with the vaccination of thousands of schoolchildren.

Contrary to the prevailing scientific belief that only live virus vaccines could be effective, Salk demonstrated that his killed-virus vaccine could safely stimulate an immune response. His team's work built on decades of polio research, including that of Isabel Morgan, whose pioneering studies in the 1940s had shown that monkeys could be successfully inoculated with a killed-virus vaccine. Salk and his team tested the vaccine on volunteers, including himself, his wife, and their children, all of whom developed immunity without adverse reactions.

Meanwhile, in the early 1960s, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using a weakened live virus. Easier to administer and more effective at providing long-term immunity, OPV became the preferred method of vaccination in many countries. The widespread use of both vaccines led to the near-eradication of polio in most parts of the world.

Image: Preparation of measles vaccine at the Tirana (Albania) Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology. Credit: World Health Organization photo by D. Henrioud via Wikimedia Commons

During this era, other major breakthroughs included the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963, following successful virus isolation by Thomas Peebles and John Franklin Enders. Enders' team tested the vaccine on children between 1958 and 1960 before launching large-scale trials in New York and Nigeria. In 1961, it was hailed as 100% effective, and the first measles vaccine was licensed for public use in 1963. A more refined version was introduced in 1968 by Maurice Hilleman, who weakened the virus further to reduce side effects, creating the Edmonston-Enders strain still in use today.

The 1960s also saw the development of the mumps vaccine by Hilleman, which was licensed in 1967. In 1971, Hilleman's team combined the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines into a single MMR shot, revolutionising childhood immunisation programmes. Within five years, more than 11 million doses of the mumps vaccine alone had been distributed, marking a turning point in global disease prevention.

1970s-1990s

The eradication of smallpox and the biotech boom

One of the greatest public health achievements of all time occurred in 1980, when the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated – the first disease eliminated through vaccination. Aggressive global vaccination campaigns had wiped out the virus, proving that coordinated immunisation efforts could change history.

In the same decade, Michiaki Takahashi successfully attenuated a strain of the varicella-zoster virus, leading to the development of a live, attenuated chickenpox vaccine. However, a US version of the vaccine would not be licensed until two decades later.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the rapid advancement of biotechnology in vaccine development. The first recombinant DNA vaccine, for hepatitis B, was developed in 1986, using genetic engineering, rather than traditional pathogen-based methods. This innovation marked the beginning of modern vaccine technology, leading to safer and more effective immunisation strategies.

_-_Oleacinidae_-_Mollusc_shell.jpeg)

Image: Preserved Varicella semitarium specimen. Credit: Naturalis Biodiversity Center/Wikimedia Commons

Vaccines for varicella (chickenpox) and hepatitis A were introduced in the 1990s, further expanding routine immunisation schedules. By the end of the century, vaccines had become a cornerstone of public health, preventing millions of deaths worldwide.

However, vaccine confidence suffered a setback in 1998 when a controversial research paper was published in The Lancet, falsely claiming a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Despite lacking any robust scientific evidence, this misinformation spread widely, causing a drop in vaccination rates. This decline led to a resurgence in measles cases in England, Wales, the US, and Canada.

Meanwhile, groundbreaking work by American scientists John Robbins and Rachel Schneerson led to the first conjugate vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae (Hib) disease. Conjugate vaccines proved more effective in infants and young children than their polysaccharide predecessors, offering improved protection to the age group most at risk from Hib infections. This vaccine ultimately replaced the earlier version and became a key part of childhood immunisation schedules worldwide.

2000s - present

mRNA vaccines and the COVID-19 revolution

The 21st Century has witnessed some of the most rapid advancements in vaccine science. In 2006, the first human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was introduced in the US, dramatically reducing cervical cancer rates. The UK rolled out its HPV vaccination programme in 2008, offering protection against a virus responsible for the majority of cervical cancer cases. Another key development came in 2015 with the European Medicines Agency's approval of RTS,S – the first malaria vaccine – marking a breakthrough in combatting a disease that still claims hundreds of thousands of lives annually.

The World Health Organization declared Europe polio-free on 6th June 2002, a major milestone in the global effort to eradicate the disease. However, the most significant vaccine development in recent times came in 2020 with the rapid creation of COVID-19 vaccines. Faced with an unrelenting global health crisis, an international race unfolded as pharmaceutical companies and governments rushed to develop an effective vaccine. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, using mRNA technology, led the charge, producing vaccines in record time.

.jpg)

Image: Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman (SEAC) Ramon "CZ" Colon-Lopez receives a COVID-19 vaccine at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., Dec. 21, 2020. Credit: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Unlike traditional vaccines, these mRNA-based shots instructed cells to produce a harmless viral protein, triggering an immune response without using live or inactivated viruses. Meanwhile, China introduced the Sinovac vaccine, which relied on a killed virus, and Russia developed Sputnik V, an adenovirus-vector vaccine. By December 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorisation for both Pfizer and Moderna's vaccines, marking a historic moment in vaccine development.

The success of mRNA vaccines led to renewed interest in personalised vaccines, including cancer immunotherapy. Several pharmaceutical companies and research institutions are now working on therapeutic cancer vaccines, which aim to train the immune system to recognise and attack tumours.

In 2023, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for their groundbreaking discoveries that enabled the development of mRNA vaccines, fundamentally altering our approach to vaccine technology.

As research into self-amplifying RNA, personalised immunisation, and next-generation vaccines continues, the future of vaccination promises even greater breakthroughs. From infectious disease prevention to cancer treatment, vaccines are poised to remain one of the most powerful tools in modern medicine, ensuring a healthier and more resilient global population.

About the Author

Eloise McLennan is the editor for pharmaphorum’s Deep Dive magazine. She has been a journalist and editor in the healthcare field for more than five years and has worked at several leading publications in the UK.

Supercharge your pharma insights: Sign up to pharmaphorum's newsletter for daily updates, weekly roundups, and in-depth analysis across all industry sectors.

Want to go deeper?

Continue your journey with these related reads from across pharmaphorum

Click on either of the images below for more articles from this edition of Deep Dive: Research and Development 2025