The rapidly changing face of oncology

Jeffrey M. Bockman of Defined Health shares his insights on the rapidly changing oncology space. He explores how we are 'poised for dramatic changes over the next decade' as we head toward more refined, personalized management in oncology.

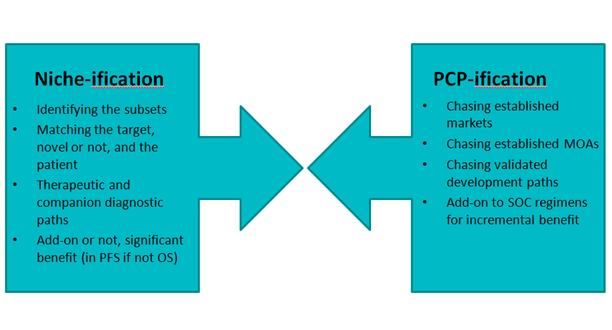

Oncology is undergoing rapid changes. It still remains a category of intense clinical development activity where Biopharma continues to see the opportunity for blockbuster products. However, the nature of the competitive landscape and the market dynamics have changed significantly since the days when Taxol and Taxotere defined the blockbuster oncology market through their extensive life cycle management—with clinical trials extending and expanding approvals within a single cancer (vertical franchise expansion) and into multiple other cancers (horizontal franchise expansion). As has been well documented, Oncology is transitioning to a great part into more niche-oriented segments, defined by molecular stratification of patients' tumors and use of biomarkers and increasingly next gen sequencing, and away from the old organ / tissue type and histopathology defined labels.

And in addition, this trend towards selected patient subsets has enabled an even faster "fast-follower" effect that is impacting clinical development strategy and market planning (and has already been seen playing out in CML with the various bcr-abl TKIs). This trend is only accelerating with numerous players moving to challenge Pfizer's crizotinib. These fast-followers are exploiting the molecular changes driven by initial therapy with the first-in-class agents (the acquired resistance mutations) and new approaches like irreversible inhibitors.

Add to this the fact that many companies are still trying to develop broadly acting agents, and are doing so in crowded spaces because the technical / scientific risk has presumably been reduced but at the expense now of increased commercial risk. Various publications, as well as we ourselves, have noted the plethora of programs continuing to target angiogenesis, probably rightly so given its importance and its validation, but the number focusing on VEGF is arguably rather excessive.

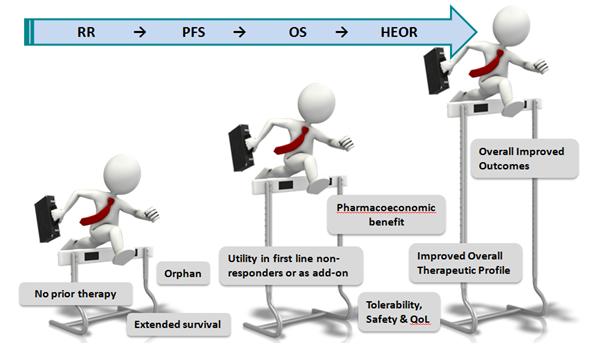

And although cancer remains a data-driven clinical and market space, nevertheless the competitiveness is now looking in some ways – with due poetic license – like the old PCP spaces where products were developed and in many cases successfully launched with minimal differentiation (Figure 1). In fact, one could argue there is a dynamic tension between two opposing trends of the old "one size fits all" approach and the personalized or precision medicine approach.

Source: Defined Health

It will be interesting to watch over the next 5 years as the ongoing changes in the overall healthcare industry intersect and interact with the fast evolving scientific and clinical advances in oncology drug discovery and development. The increasing pricing pressures, which until recently had left the oncology market as relatively sacrosanct, have now begun to exert themselves, and the recent spate of controversies such as Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center's flagging the high price of Zaltrap and the Blood article by Kantarjian et al in April of this year1 on the high price of CML drugs, underscores this shift in attitude and policy.

"...there is a dynamic tension between two opposing trends of the old "one size fits all" approach and the personalized or precision medicine approach."

Such a dynamic reinforces the need for bringing forward drugs that provide not simply marginal or incremental benefits but that truly provide clinically meaningful, relevant value (although there are clearly high unmet need cancer settings in which any drug that offers some benefit and hope can be viewed as having value). And certainly the trend has been for the bar to continue to be raised at regulatory agencies and for what clinicians, and now payers, need to see (Figure 2).

Figure 2: the trend in oncology has been for the bar to continue to be raised at regulatory agencies and for what clinicians, and now payers, need to see.

Source: Defined Health

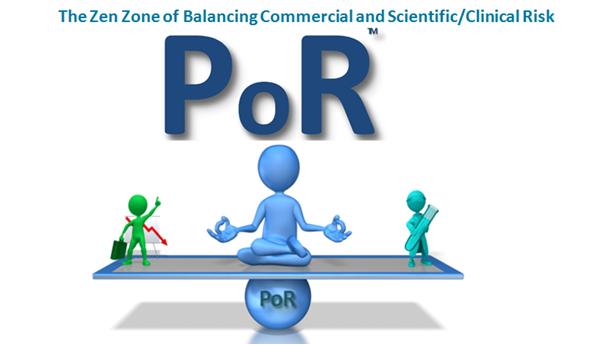

Such new demands on drugs now extend to the benchmarks that large Biopharma companies look for when they assess prospective external in-licensing or M&A opportunities. In fact, the onus on new drugs, most critically for small biotechs looking for partners, should be not on simply proof of Concept (PoC) but Proof of Relevance (PoR), seeking for more innovative than incremental value. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: The onus on new drugs, most critically for small biotechs looking for partners, should be not on simply proof of Concept (PoC) but Proof of Relevance (PoR)

Source: Defined Health

The idea is that while demonstration that a drug works is necessary, in a time when simply having a novel mechanism to promote cannot justify high pricing of drugs, it is no longer sufficient. So the best path forward, especially for the small biotech, is to do the "killer experiment," where the clinical relevance is demonstrated or at least intimated. While this idea of going after resistant cancer cells and refractory patients has been almost standard of practice for oncology drugs, in many other disease areas it has not. And with the adoption of this more rigorous PoR, one has seen many leading Pharma companies kill programs around new MOAs not because they did not work, but because they would not be differentiated from already approved established standard of care products that were or would soon be going generic.

"...the best path forward, especially for the small biotech, is to do the "killer experiment" where the clinical relevance is demonstrated or at least intimated..."

An example of the demonstration of PoC and the suggestion of PoR in oncology that enabled an early stage partnering event can be found with SymphoGen's next generation anti-EGFR program Sym004 that was partnered last year with Merck KGaA. In this case, early data was suggestive of more complete inhibition of ligand binding and EGFR activation, with increased EGFR degradation precluding ligand-independent signalling via interaction with other receptors, and ultimately to the possibility of the product being less susceptible to resistance due to increased EGFR ligand production. Hence, the potential for Sym004 to truly be better than Erbitux or Vectibix.

Oncology is poised for dramatic changes over the next decade as scientific discovery and technological innovation spur more refined, personalized management of each patient's cancer. And the increasingly competitive pipeline and marketplace, and the demands of regulators and payers, will continue to place new pressures on the performance criteria of these drugs. Meanwhile, the heterogeneity of each individual's particular tumor both at initial diagnosis, and as it evolves in a Darwinian fashion under therapeutic intervention, will continue to pose challenges that academia and industry will need to confront.

References

1. Experts in chronic myeloid leukemia*, Price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), reflection of the unsustainable cancer drug prices: perspective of CML Experts Blood doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490003 Apr 2013

About the author:

Jeffrey M. Bockman, PhD is a Vice President at Defined Health. Jeff's scientific expertise encompasses a broad range of therapeutic disciplines for which he serves as Team Leader or internal consultant, including Oncology, Infectious Disease (especially HIV, hepatitis, and antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections), Inflammatory Disorders (especially asthma and psoriasis), Complex Therapeutics (cell and gene therapy) and Drug Delivery. Jeff also has extensive commercial and strategic perspective on the pharmaceutical and biotech industries. He has directed hundreds of in-depth licensing opportunity and valuation assessments during his tenure at DH.

Before joining Defined Health, Jeff was a Senior Research Scientist and Research Project Leader in the commercial development of oligonucleotide therapeutics for viral diseases and cancer at Innovir Laboratories; and an Assistant Research Professor at The George Washington University School of Medicine. He has worked with two Nobel Prize recipients: Dr. Sidney Altman on ribozymes, and Dr. Stanley Prusiner on prions, and holds four patents in applications of ribozymes as therapeutics and diagnostics.

Jeff is a member of the Licensing Executives Society, the American Association for Cancer Research, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. He received a BA from University of California at San Diego, a PhD in Medical Microbiology from the University of California at Berkeley, and an MA in English/Creative Writing from New York University.

He can be contacted at jbockman@definedhealth.com

Closing thought: What will the oncology space look like in ten years?