A new age: the real-world development pathway

The emerging era of personalised medicine means new, pragmatic approaches will focus increasingly on real-world evidence. In this new environment, pharma must be prepared to work collaboratively to establish the best benefit-risk profiles and outcomes, say Sarah Athey and Volker Rönicke.

In spite of increasing spending on research and development, from $54 billion in 2000 to $143 billion in 2015[i], and falling productivity, from 10 drugs per $1 billion spent in 1970 to one per $1 billion in 2015[ii], the classical drug development approach has largely persisted. However, significant unmet need for new medicines remains, with approved treatments for only 500 of the 10,000 known diseases[iii].

Sarah Athey and Volker Rönicke

In recent years, the ability to identify niche patient populations through biomarker or genome screening has meant that treatments are targeted at the population most likely to respond. This means that the patient population for new treatments is generally much smaller and the traditional development model, relying on large, randomised clinical trials (RCTs), is less feasible. Stakeholders across the biopharmaceutical industry, regulators, payers, providers and patients agree that an updated development approach for the 21st century is needed to give patients timely access to important, affordable new treatments.

New regulatory frameworks setting the stage for change

In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced the breakthrough designation status for life-threatening diseases[iv]; an expedited development, review and approval process based on proof of concept (PoC) with a focus on early consultation and ongoing dialogue between sponsor and regulator. Among the 42 products approved via this route between 2012 - September 2016[v] was pembrolizumab, indicated for patients with advanced melanoma. Conditional approval was based on data from a surrogate endpoint (tumour size) even though, at the time of approval, there was no proof of increased survival or reduction in disease-related symptoms. However, the sponsor committed to performing these confirmatory studies[vi].

In June 2016 the Bipartisan Policy Center published a report with recommendations to integrate real-world evidence into development programmes early to accelerate patient access to medicines[vii]. It followed the launch, on 7 March 2016, of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) PRIME (PRIority MEdicines) pathway, which provides extensive sponsor/regulator dialogue to support the earliest possible approval for assets that treat conditions with high unmet medical need[viii]. Since its launch, there has been huge interest in the PRIME pathway, with 64 applications received[ix].

This means that, providing an asset meets the criteria, accelerated approval is now available in countries that represent more than two thirds of the global prescription drug market. It is a particularly important milestone and the first step towards a broad ‘launch at PoC’ development model.

Pragmatic trials needed from early development to post approval

With smaller patient populations, identifying patients who will potentially benefit from targeted treatments is a challenge. A useful strategy to mitigate this is use of patient registries to match patients to treatments based on their genomic profile and clinical outcomes. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) launched its Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilisation Registry (TAPUR) study in March 2016[x]. The trial is evaluating molecularly-targeted cancer drugs and collecting data on clinical outcomes to inform additional uses of these drugs outside approved indications. These types of study have the potential to inform inclusion/exclusion criteria of resulting phase 3 programmes, shorten often lengthy patient recruitment times and improve patient retention in trials compared with the classical development approach.

The next step is to integrate pragmatic trials into phase 3 development programmes. Pragmatic trials are defined, in this context, as those that randomise patients to active treatment versus standard care, in a care setting with significantly relaxed inclusion/exclusion criteria and without a stringent study protocol.

Historically, conducting pragmatic trials with treatments that have no marketing authorisation was not covered by regulatory frameworks. However, the Salford Lung Disease Study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) pioneered this transition. This study combined an approved active pharmaceutical ingredient in a non-approved medical device and compared it to standard COPD care. The benefit and crucial feasibility driver of this pre-approval, pragmatic trial was the data density and high connectivity of the Salford provider system - something that we call a pseudo-real-world-environment.

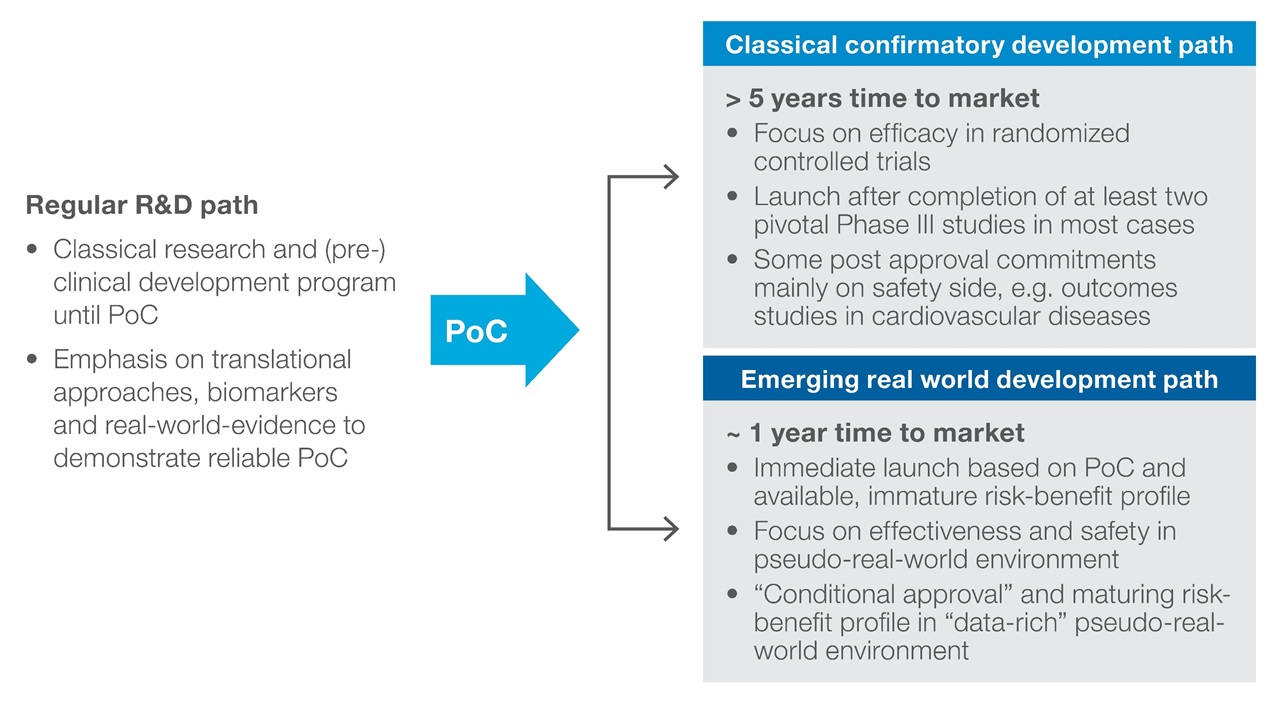

It is likely that the journey will continue with pragmatic trials as part of phase 2 development programmes and that the new normal will be conditional approvals granted shortly after PoC for a broad spectrum of therapeutic areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Early conditional approval in a restricted population with active surveillance post-launch

Adopting a data-rich approach to decision making optimises clinical programme design and execution

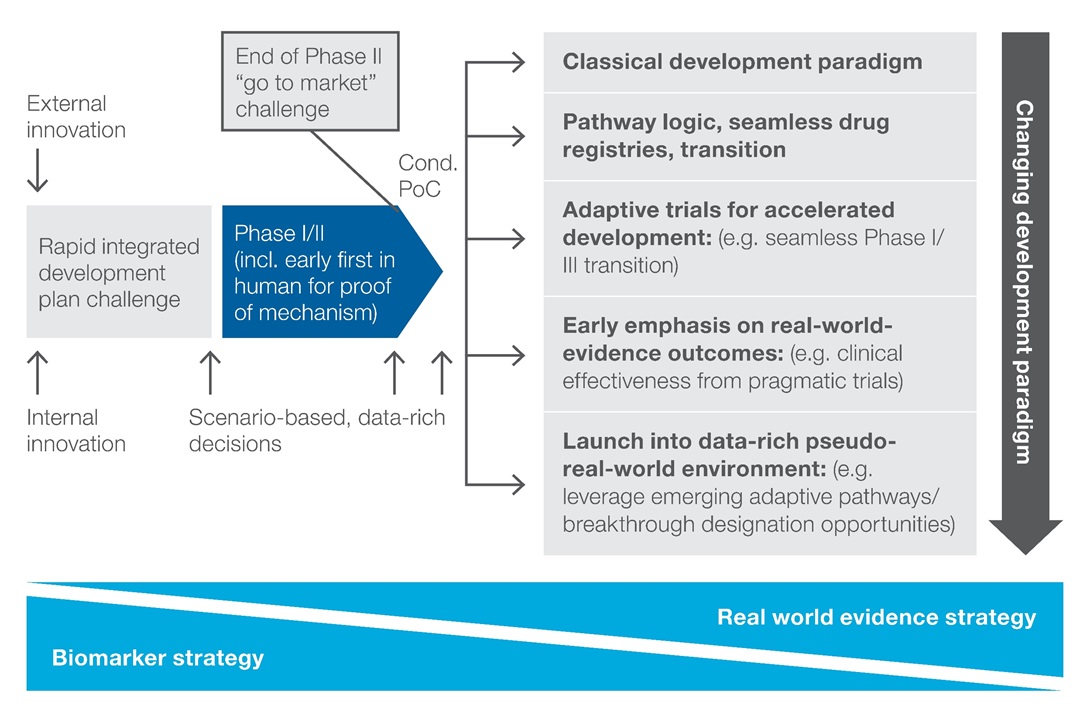

The emerging opportunity to benefit from ‘launch at PoC’ forces drug developers to make strategic trade-off decisions about the optimal development path for an asset on an indication-by-indication basis. The options start with the classical development model with incremental steps to the new, data-rich pseudo-real-world environment option (Figure 2). It requires acceptance that a real-world setting is the better environment in which to fully understand the safety profile and not the classical development paradigm of RCTs.

Figure 2: Iterative trade-off decisions on therapeutic areas, disease indications for meaningful prioritization and end-to-end stewardship of priority projects

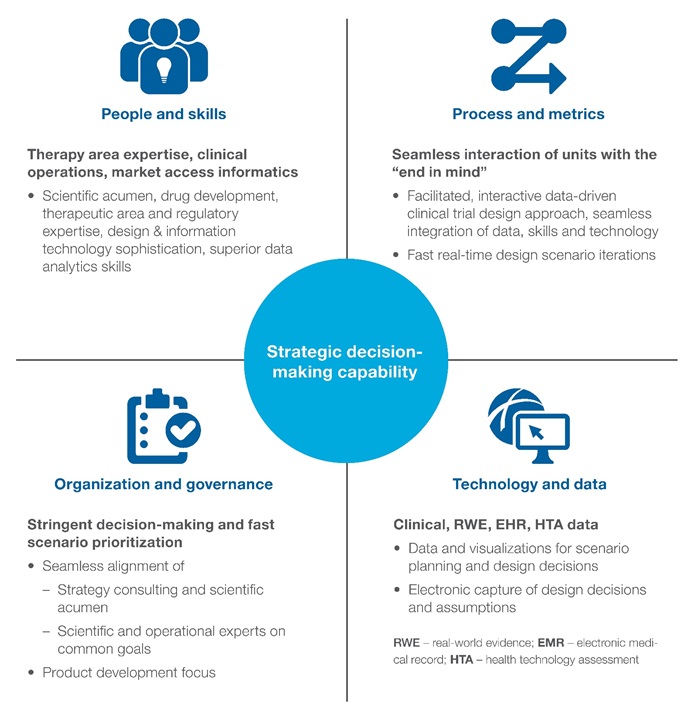

Even if this approach reduces or eliminates the cost of phase 3, investment to generate additional risk-benefit information is still necessary. This includes information in support of additional label claims as the eligible patient population expands. A data-rich, scenario-based, decision-making capability is required to make conscious decisions for each asset and each indication to understand and manage the resulting benefit-risk profile. This is a highly collaborative approach, bringing together knowledge in the form of internal and external data and expertise (Figure 3). The process generates options with clinical and financial trade-offs that inform the best path forward.

Figure 3: Essential features of a modernised drug development decision-making capability

There are implications for operational delivery, too, since this development model is characterised by highly interconnected data sources where technology plays an important role. In the pseudo-real-world environment high, connectivity between prescribers, caregivers, patients, payers and other relevant stakeholders allows early detection of expected and unexpected adverse events and is optimised for fast correction/remediation 24/7.

There is no doubt that launch at PoC has potential benefits. However it is not without risks for the sponsor. It means that products enter the market with less mature benefit-risk-profiles and thereby a weaker evidence package as basis for negotiation with payer organisations. This represents a challenge in an environment where the reimbursement value can only go down. Payers would need to adopt payment-for-performance approaches, in order to allow for a growing reimbursement value in line with richness of benefit-risk and comparative-effectiveness evidence.

Conclusion

The elements needed to modernise development are coming together. Regulators have created the frameworks needed to achieve early conditional approval with close follow-up post launch to manage the emerging, real-world, product profile. Sponsors are already working collaboratively with regulators and payers. However, to realise the vision for launch at PoC, payers need to move towards payment for performance. If this can be achieved, there is every reason to believe that this vision is the future development model.

References:

[i] Data Monitor. (2016). Financial Analysis for Big Pharma. (accessed March 2016)

[ii] Bipartisan Policy Center. (June 2016). Using real-world evidence to accelerate safe and effective cures. Washington DC: BipartisanPolicy.org. (accessed October 2016)

[iii] US Congressional record. (2015). 114th Congress 1st Session., (p. 161 (106)). Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/2015/7/9/-house-section/article/h5008-1 (accessed October 2016)

[iv] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2014, Sep 15). Breakthrough Therapy. Retrieved from U.S. Food and Drug Administration: http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Approvals/Fast/ucm405397.htm (accessed October 2016)

[v] FDA: CDER Breakthrough Therapy Designation Approvals. (2016, 9 30). CDER Breakthrough Therapy Designation Approvals. Retrieved from FDA: CDER Breakthrough Therapy Designation Approvals: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/drugandbiologicapprovalreports/indactivityreports/ucm373559.htm (accessed October 2016)

[vi] FDA News Release. (2014, September). FDA approves Keytruda for advanced melanoma. Retrieved from FDA news release: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm412802.htm (accessed October 2016)

[vii] Bipartisan Policy Center. (June 2016). Using real-world evidence to accelerate safe and effective cures. Washington DC: BipartisanPolicy.org. (accessed October 2016)

[viii] European Medicines Agency: Prime Pathways. (2016, March 07). European Medicines Agency Guidance for applicants seeking access to PRIME scheme. Retrieved from EMA: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2016/03/WC500202630.pdf (accessed October 2016)

[ix] European Medicines Agency. (2016, October 7). EMA Management Board: highlights of October 2016 meeting - press release. Retrieved from European Medicines Agency: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2016/10/news_detail_002616.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1 (accessed October 2016)

[x] American Society of Clinical Oncology. (2016, March). Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) Study. Retrieved from http://www.tapur.org/ (accessed October 2016)

About the authors:

Sarah Athey is Engagement Leader, Consulting Services, and Volker Rönicke works in Consulting Services, at QuintilesIMS.

Sarah Athey has 25 years of industry experience. She has worked as a health economist developing market access/launch strategies in Europe and Asia. She won the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) chief executive’s award for innovation for her work with Seoul University and the Korean government.

Before joining QuintilesIMS, she worked at PriceWaterhouseCoopers, IBM and GSK. She has a BSc in Zoology and Pharmacology, plus an MBA and an MSC in Health Economics.

Volker Rönicke has more than 20 years of experience as a senior strategic advisor and has worked for biopharma and biotech firms.

Previously he was Partner with Booz & Company (now Strategy&). He holds an MBA from Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, and a PhD in molecular biology and cell biology from Max-Planck Society and Philipps University, Marburg, Germany.

Read more:

The EMA's Adaptive Pathways: are safety concerns exaggerated?