How eligible patient numbers affect price of rare disease drugs in France

Having recently assessed the relationship between drug price and prevalence of non-oncology rare diseases, CRA’s Life Sciences Practice team explores in greater depth the situation for these orphan drugs in France in this final article of a three-part series.

Pricing and market access in France operate on a dual system, under which health technology assessments (HTAs) are conducted separately from pricing negotiations. The HTA body, the CT (Commission de la Transparence – Transparency Commission), is charged with providing guidance to inform pricing negotiations in two main forms: a comparative clinical benefit rating, the ASMR (Amélioration du Service Médical Rendu), and a target patient population.

Rare diseases: a flawed system

In the case of rare diseases, however, the French system is flawed, as establishing a comparative clinical benefit of orphan drugs is dependent on a comparator drug, which is often not available. Also, sizing a target patient population becomes harder as prevalence decreases and local epidemiology data are not as robust. This leaves the pricing committee, CEPS (Comité Economique des Produits de Santé), with many uncertainties to manage in pricing negotiations. In addition, with healthcare budgets under increasing pressure and many orphan drug launches in the past few years, the value of rarity must be spread more thinly.

The team at CRA set out to understand how French payers manage these uncertainties and assess the value they place on rarity. Its study analysed 22 non-oncology orphan drugs that received European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval between July 2012 and the end of 2019 and focused on chronic, non-curative treatments for which payers are more likely to scrutinise annual treatment costs (ATCs). Given that some orphan drugs have multiple indications, CRA focused on the first assessment and first negotiated price to determine ATC at that time.

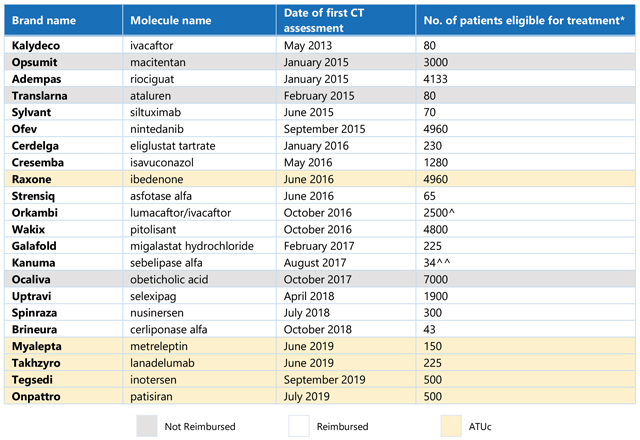

Table 1. List of non-oncology orphan drugs and number of patients eligible for treatment in France. *Average provided where CT noted a range for number of patients; patient number listed for Orkambi is a combination of the first three indications assessed by the CT, given a reimbursed price was only made available following assessment of the third indication; Kanuma patient number is calculated for the reimbursed population (rapidly progressing, infant onset), based on total lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) patient population defined by the CT, and ATUc data regarding the proportion of diagnosed patients that are treated and the proportion of patients that are characterised as “rapidly progressing, infant onset.” (Source: CT assessments [Haute Autorité de Santé website]; ANSM [Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé]; CRA analysis)

Relationship between ATC and eligible patient number

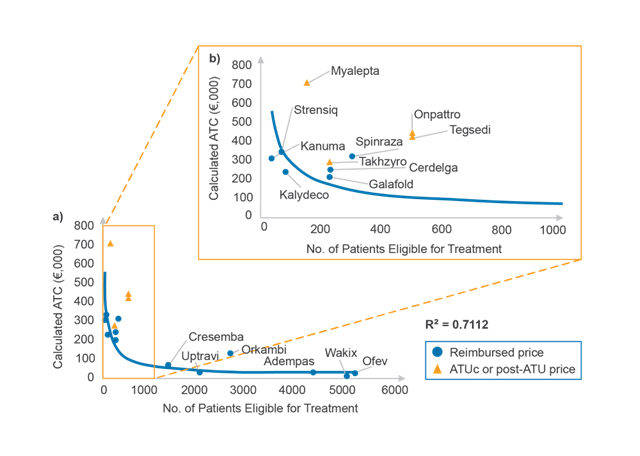

In accordance with previous findings across EU5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK) and Japan, CRA analysis shows a correlation between reimbursed ATC and eligible patient number (an indication of disease prevalence) in France, in which ATC decreases as eligible patient number increases (as shown in Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Relationship between ATC and eligible patient number (a) for all products and (b) for products with fewer than 1,000 patients eligible for treatment according to the CT. (Source: CRA analysis)

Looking more closely at products with fewer than 1,000 patients eligible for treatment (as shown in Figure 1b), prices of drugs made available through the early access programme ATUc (Autorisation Temporaire d’Utilisation dite de cohorte, since July 2021 known as the AAP, autorisation d'accès précoce) tend to sit above the trendline. This is because ATUc prices are not negotiated and are determined by drug manufacturers for the duration of both ATUc and post-ATUc periods. However, these prices bear little risk to the Society Security (Securité Sociale) in France as lower CEPS-negotiated prices are subject to payback of all or part of the difference.

The change in ATC for Kalydeco after indication expansion offers an interesting example of the importance of eligible patient number in pricing negotiations in France. Kalydeco was first assessed by the CT in May 2013 for treatment of cystic fibrosis patients of a minimum of six years old and carrying at least one G551D mutation in the CFTR gene, with an estimated eligible patient population of 80 and an ATC of approximately €235,000. Kalydeco obtained an ASMR 2 rating (important improvement, eligible for EU-level price) for this indication, so discussions with CEPS would have focused on patient numbers. In October 2019, the CT assessed Kalydeco for an expanded indication in multiple additional mutations, for a total additional five eligible patients, and again obtained an ASMR 2 rating. Since the assessment, Kalydeco’s ATC has decreased to approximately €220,500 – a change almost exactly inversely proportional to the population increase.

Additional factors beyond eligible patient number

In CRA’s analysis, it was found that there were several instances – for example, as seen with Spinraza and Orkambi – where prices sit above the trendline, offering valuable insights into important factors within pricing negotiations beyond eligible patient number. To better understand the relationship between drug price and disease prevalence, the study investigated additional factors that may come into play during pricing negotiations, including:

- ASMR rating – evaluation of a drug’s improvement in medical benefit compared to the current standard of care, on a rating scale from 1 (major improvement) to 5 (no improvement). ASMR ratings directly feed into the CEPS’ determination of appropriate list price relative to pricing comparators.

- Use of ATUc data in CT assessment – extent to which cohort-level patient data collected during the ATUc period were used in CT assessments, classified as “Data used in main efficacy analysis,” “Data used elsewhere in assessment,” “Data not used,” or “No ATUc.”

Despite the high unmet need generally perceived in rare diseases, the number of unfavourable ASMR ratings (i.e., ASMR 4 or ASMR 5) illustrates the challenges for drug manufacturers in providing robust clinical data, as well as the importance of the availability of a clinical comparator or existing treatment. The findings also demonstrate that, unlike in Germany where the G-BA (Gemeinsamer Bundesauschuss – Federal Joint Committee) automatically grants orphan drugs at minimum an “unquantifiable added benefit” rating upon initial assessment – only reassessed if annual sales revenue exceeds €50 million – orphan drug designation does not guarantee a positive assessment in France.

The ATCs for orphan drugs with the highest ASMRs (Kalydeco, Strensiq: ASMR 2; Kanuma: ASMR 3) were among the highest ATCs in this analysis, suggesting a relationship between ASMR rating and ATC. It is important to note that prices of ASMR 1-3 products are freely set up to the average price across Germany, the UK, Spain, and Italy, and only volume is negotiated with CEPS in France. Thus, these high prices are not intrinsically indicative of a higher payer willingness to pay.

The analysis also shows that some orphan drugs with lower ASMR ratings achieved relatively high ATCs, including Galafold (ASMR 4) and Cerdelga (ASMR 5). The relatively high prices of these products suggest that the relationship between ASMR rating and ATC includes other factors such as disease prevalence, unmet need, availability of a clinical or pricing comparator, and the robustness of clinical data.

Influence of ATUc programme on drug pricing

Most reimbursed drugs reviewed in CRA’s analysis (15/17) were previously available through the ATUc, reflecting the purpose of the programme: to provide access to much needed drugs developed to treat serious or rare diseases, when no appropriate treatment exists, and the initiation of treatment cannot be delayed.

The majority of CT submissions (9/15) did not include the cohort-level real-world patient data collected in the ATUc period. Of the remaining six submissions, only three used ATUc data to support the main efficacy assessment; the other three used the data to support other elements of the assessment, for example, as evidence of product usage and dosing regimens.

It was found that the inclusion of ATUc data in CT assessments was not associated with more favourable ASMRs or higher ATCs. For example, despite inclusion of ATUc data in the main efficacy assessment of Uptravi, it did not appear to influence the ASMR rating. Uptravi received an ASMR 5, primarily based on methodological considerations, including lack of comparative data and use of a surrogate primary endpoint. Myalepta is another example where ATUc data did not help mitigate a low ASMR rating (4 and 5 in generalised lipodystrophy and partial lipodystrophy, respectively). While the ATUc data confirmed efficacy on surrogate outcomes (HbA1c and triglyceride levels), it did not make up for lack of conclusive evidence regarding impact on mortality.

The lack of value placed by the CT in the ATUc data could reflect the importance of other factors, such as unmet medical need and the existence of a clinical comparator. It demonstrates that, while an ATUc serves as an opportunity to gather real-world evidence before EMA approval, it does not substitute for methodologically robust, comparative, trial-based data. CRA’s findings also showed that not all products that were granted expanded access through the ATUc programme successfully achieved reimbursement.

Conclusion

Payers in France seem to value treatments for rare diseases, although a range of factors are shown to influence the achieved price. The CT assessment is likely critical to successfully achieving a premium list price for rare disease drugs, which depends on submitting robust clinical data. Small target patient populations and orphan drug status will not exempt manufacturers from presenting comparative clinical data, if possible, or deter the CT from granting low ASMR ratings. Provision of real-world evidence, even specific to the French healthcare system, such as ATUc data, is also not a surrogate for randomised comparative clinical trials in the minds of French payers. While France should still be seen by orphan drug manufacturers as an attractive market where high list prices are achievable, the specific evidence requirements should be considered early in the drug development process to maximise pricing outcomes.

The first and second articles in the series can be found here and here.

About the authors

Cécile Matthews is a vice president in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA with over 20 years of experience in strategy consulting for the pharmaceutical industry. Her areas of expertise include pricing, reimbursement, and market access globally, and she is an expert in the French system.

Cécile Matthews is a vice president in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA with over 20 years of experience in strategy consulting for the pharmaceutical industry. Her areas of expertise include pricing, reimbursement, and market access globally, and she is an expert in the French system.

Bhavesh Patel is a principal in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA and directs CRA's Rare Disease Issues Leadership Platform. He has experience in global pricing and market access, value proposition, commercial strategy, and launch readiness.

Bhavesh Patel is a principal in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA and directs CRA's Rare Disease Issues Leadership Platform. He has experience in global pricing and market access, value proposition, commercial strategy, and launch readiness.

Owen Male is a consulting associate in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA. His experience includes global pricing and market access, value proposition, and commercial strategy.

Owen Male is a consulting associate in the Life Sciences Practice at CRA. His experience includes global pricing and market access, value proposition, and commercial strategy.

The views expressed herein are the authors’ and not those of Charles River Associates (CRA) or any of the organisations with which the authors are affiliated.