Healthcare evidence development: guilty until proven innocent?

With increasing importance placed on evidence in support of new drug applications, pharma must prepare its case meticulously to support its candidates in front of a judge and jury of stakeholders.

The evidence required to support pharmaceutical and medical device products is undergoing a historic evolution in the US, driven by changes in policy, regulation, and economics, as well as the increasing availability of real-world data and new technologies. Consider these recent events and their impact on evidence development:

- Early and late phase clinical evidence is now integrated through fast-track designation.

- Real-world evidence (RWE) will be formally considered by regulatory authorities for product label and approval decisions through the 21st Century Cures Act.

- Database analyses will be conducted by the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), with engagement from manufacturers, to study Emerging Safety signals in Medical Devices.

Also consider the slew of acronyms representing changes that have been ushered in over the last five years: PCMH, OCM, ACO, ICER, ASCO, MCDA, PPACA, and FDAMA.

Given this paradigm shift, the industry must address two critical questions: ‘Have we kept up?’ and ‘Can we do better?’ Today’s scepticism of the pharmaceutical industry from politicians and the public hints that the answer is ‘no’. So, as an industry, we must reinvigorate the evidence supporting our products.

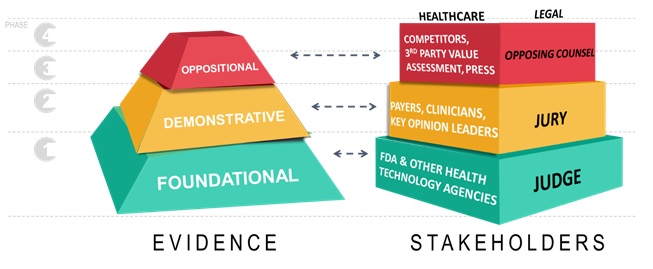

The legal profession is an excellent source of inspiration to overcome the ‘guilty until proven innocent’ environment facing pharma. To succeed, we must establish new foundational, demonstrative, and oppositional frameworks for evidence development to effectively communicate the value of our products to key stakeholders.

A court of health & medicine

In an American courtroom, evidence that informs a persuasive, central argument must be:

- Foundational: Facts of the case

- Demonstrative: Illustrative to common sensibilities

- Oppositional: Proactive to discourse and sound to opposition.

Evidence-based arguments are aimed at a predictable audience – judge, jury, and opposing counsel. Relatedly in healthcare, arguments are tailored to a court comprised of the FDA, payers/health care professionals and competitors/value assessors.

Also related are decision processes. Just as a judge endorses a legal proceeding and presides over a courtroom, the FDA approves products for the marketplace and defines the parameters by which manufacturers can compete, communicate, and leverage evidence-based arguments. In our case, the ‘jury’ consists of those payers, prescribers, and health authorities that determine whether an argument is worthwhile to their patients and populations, and ultimately determines commercial success or failure.

Finally, the ‘opposing counsel’ is made up of those entities that seek to critique, rebuke, or otherwise distract from a central narrative – competitors, third-party value assessment agencies, and the press.

Introduction to evidence frameworks: foundational, demonstrative, and oppositional

Foundational evidence in law encompasses preliminary arguments in a closed court to determine the facts and merits of a case. In healthcare, evidence at this phase is focused on the judge, the FDA, who reviews submissions of core evidence (traditionally, large, randomised clinical trials) and decides whether we can proceed to formal arguments in the marketplace. In this capacity, regulatory authorities act as the first hurdle to access, and their rules underpin all the activity for the remainder of our time in the marketplace. These rules are not subject to interpretation or persuasion. They are rooted in precedent and existing statute, so the standards of the judge/FDA are predictable. With the judge granting us the right to participate, our jury determines next whether our argument is a winning one.

Demonstrative evidence is the formal communication with a ‘jury’ of payers, prescribers and health authorities. Manufacturers communicate the worth of evidence through a value proposition, appealing to the most important value drivers for each of a growing number of access stakeholders, across topics including burden of illness, safety, efficacy, and economic value. Effectively communicating demonstrative evidence is crucial in today’s environment due to a growing number of access decision makers and an increasingly restrictive environment.

The healthcare jury is a diverse group of payers and caregivers, all asking the question: ‘Why should I pay for, and use, your product?’ In a legal proceeding, demonstrative evidence is communicated through direct witnesses, the admission of critical items, and expert testimony. In our healthcare court, the tools of evidence to bolster arguments include dossiers, value stories, models, RWE, registries, patient support programmes and publications. The newest tool, RWE, is an extraordinary and powerful resource not yet exploited to its full potential, providing outcomes measures customised to the customer’s specific patient population -- akin to deposing a key witness in a court of law.

The development of oppositional evidence is the final challenge to our commercial preparation and activity. Third-party value assessors, competitors, policy makers and key opinion leaders (KOLs) will probably provide counternarratives, muddling public perception of our product’s value. Danger lurks when the opposing side’s narrative spreads and becomes the dominant perspective. In a blink, all of the time and energy devoted to the central narrative can be undone by the opposition. It is critical to anticipate and respond to these forces to keep control of our product’s narrative both at launch and throughout the product lifecycle.

May it please the court

So, how can we achieve success with evidence in pharma? The answer is close trial and testing of fact. In the development and marketing of pharmaceutical products we must invite inspection and cross-examination through transparent and rigorous evidence and user-friendly and easy-to-understand data and resources. If we present evidence in this way, we induce impartial consideration by our customers, transcending their preconceptions and biases.

In both the legal and pharma realms, to do this effectively we must understand the members of our jury and then speak to their intrinsic needs. Big data is the informatics opportunity. Using claims, electronic medical records (EMR), labs and other observational data sources we can view our customers from various perspectives to understand their individual patient populations, prescribing, and care challenges. The bar is higher for inspection and cross-examination today, for several reasons:

- Stakeholders are more sophisticated

- Healthcare spending austerity has ushered in a cost-containment challenge, and

- New mechanisms for review (multiple criteria decision analysis, micro simulation, outcomes contracting) and contracting (outcomes-based, risk sharing) are being adopted.

This trend is happening across the industry. Whether it’s the patient actively researching his/her care, the payer managing their population, the hospital executive optimising cost centres, or the physician making complex treatment decisions, the ubiquity and increasing importance of evidence is undeniable.

Closing arguments

The evolution of the courts and of pharmaceutical development and commercialisation are not so different. As the industry expands its reach to rare diseases and orphan populations with high burdens of illness, we face a sceptical judge and jury, and a tenacious opposing counsel. To survive in this ‘guilty until proven innocent’ environment, we must develop evidence that cannot be disputed by judge (FDA), jury (payers and providers) and opposing counsel (KOLs, policy makers, third party value assessors).

The foundational, demonstrative, and oppositional evidence framework blasts through traditional silos for evidence development, combining early and late stage clinical, health economic, epidemiologic, and real-world evidence around a key stakeholder focus. Big data and RWE help understanding of the inherent demands and challenges of these stakeholders as the rigour and sophistication of the industry progresses. With a renewed focus on evidence development and communication, we can promote open and honest discussion and serve the best interests of our number one client -- the patient.

About the authors:

(Left to right) Karl Freemyer, Diana Amari, Steve Arikian, Frank Corvino and Marko Zivkovic.

Frank Corvino, Marko Zivkovic, Karl Freemyer, Diana Amari and Steve Arikian work for Genesis Research, an international healthcare consultancy providing end-to-end evidence development, optimisation and communication for the life sciences industry.

Frank Corvino PhD is Managing Partner and head of Real World Evidence (RWE), supporting epidemiology, health outcomes, marketing sciences, and market access functions.

Marko Zivkovic PhD is Chief Scientific Officer, managing analysts and developing technology systems that support and leverage HEOR and real-world data.

Karl Freemyer is Director of Strategic Partnerships, helping clients to address key challenges and conceptualise unique consulting solutions.

Diana Amari PhD is Director of Outcomes Research, with over nine years of experience in biological and biomedical science and research, five focused on strategic HEOR and market access.

Steve Arikian MD is Managing Director and has over 25 years of experience in epidemiology and outcomes research. A doctor and healthcare researcher by training, he has worked on the industry side leading a health outcomes group and as a consultant.