Unlocking the future of neurodegeneration research: How automation and organoids are transforming the field

Effective treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s remains a major scientific priority. Decades of research have yet to deliver significant advancements in treatment while incidence rates are increasing driven by ageing populations worldwide.

One key barrier is the lack of robust model systems that accurately reflect the complexity of the human brain. Traditional mammalian animal models like mice cannot support the scale of screening required for drug development, while 2D model systems have proven inadequate for capturing disease complexity.

As someone with a sound scientific background, immersed in the technical side of this work, I’ve seen firsthand how the field is now reaching a pivotal point – with two converging forces playing a key role: the emergence of brain organoids and the advent of automation, the latter being essential for the high-throughput approaches that drug development demands.

Why traditional models fall short

For much of biomedical history, researchers relied on animal models or immortalised cell lines to study the underlying mechanism of human brain diseases. But the human brain is the most complicated and highly organised structure in the known universe – no animal possesses a brain that truly mirrors ours, either in complexity or in longevity. This gap poses a fundamental problem: many neurodegenerative disorders manifest only in ageing humans. Animals simply do not live long enough for the disease process to unfold. Furthermore, certain human brain features, such as the highly developed cortex necessary for studying neurodegenerative diseases, are simply absent in other species. The result? An unsatisfactory mismatch between the diseases we most urgently wish to study and the tools available to study them.

Organoids: A game-changer for human brain research

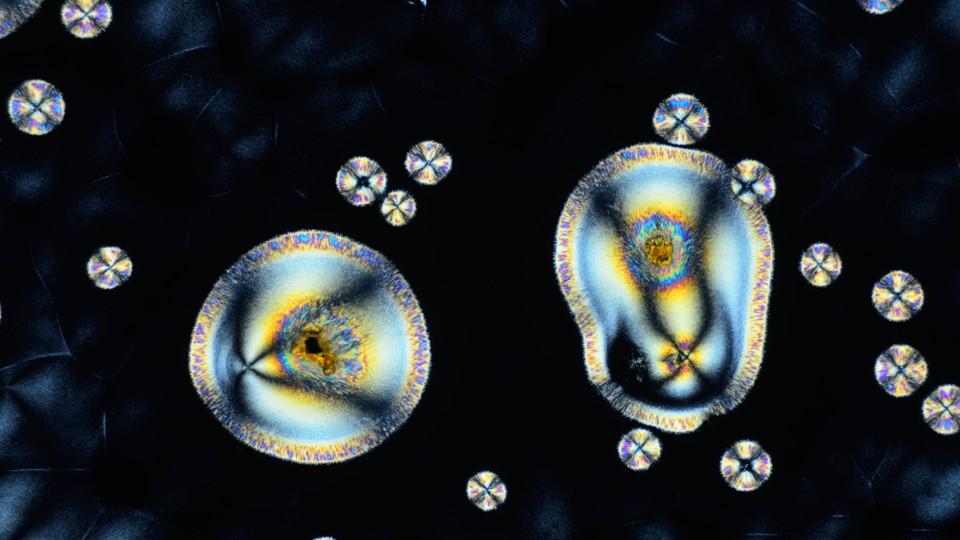

The advent of brain organoids – three-dimensional, miniaturised, and simplified versions of the brain grown from human stem cells – has launched a new era in neuroscience. Since the first brain organoids were reported just over a decade ago, these models have enabled us to mimic key aspects of human brain development and disease in ways that were previously impossible. What makes organoids so powerful is their ability to mimic key aspects of a human brain in a scalable and reproducible format. By differentiating human stem cells, we can generate tissue that closely mimics various regions of the brain. We can manipulate these cells using technologies such as CRISPR, introducing specific mutations or risk factors to model particular diseases. Importantly, we can even “age” organoids – exposing them to stressors or genetic changes to accelerate the development of disease-related features, such as the amyloid plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s. In addition, organoids can be generated from patient-derived material. This means we can grow brain tissue from both healthy individuals and those with neurodegenerative diseases, providing a unique window into personalised medicine.

Importantly, while much focus on neurodegenerative diseases centres on ageing populations, organoids provide an equally powerful and unique tool for tackling paediatric disorders. In these cases, early intervention studies can be conducted in vitro, testing different drug combinations on patient-specific organoids before administering the most promising regimen to the child – a process that has already shown promise in improving the quality of life for some patients.

This versatility across age groups – from paediatric conditions to age-related neurodegeneration – demonstrates the broad therapeutic potential that organoid technology offers across the entire spectrum of neurological disease.

However, to fully harness organoids’ potential for drug discovery, they must be produced at scale with consistency – something not achievable through manual lab work – making automation essential. This is a synergy we'll explore further.

The bottlenecks: Scale, consistency, and human limitations

Yet, despite these remarkable advances, organoid research still faces significant hurdles. Culturing organoids by hand requires strict adherence to protocols and feeding schedules that can stretch over 100 days or more for some brain model systems. The reality of modern research life – weekends, holidays, the unpredictability of daily schedules – inevitably introduces variability. Every lab, and often researchers within labs, tend to develop their own version of protocols, hampering reproducibility and making cross-study comparisons difficult. Scale is another persistent obstacle. Large-scale drug screens or longitudinal studies involving hundreds or thousands of organoids are simply beyond the capacity of manual methods. Even acquiring the necessary monitoring data – such as daily imaging of dozens of plates, each containing multiple organoids – is a monumental, if not impossible, task for a human alone.

Automation: Overcoming bottlenecks and opening up new possibilities

This is where automation enters as a true catalyst for change. By automating the cultivation and monitoring of brain organoids, we address several critical pain points at once. First and foremost, automation brings reproducibility: protocols are executed identically, every time, across every sample and across geographic locations. This level of consistency is indispensable for both basic research and translational studies, where even small deviations can lead to irreproducible results.

Automation also enables scalability. Automated systems can handle far more samples than any human could, adhering to strict feeding and passaging schedules that are maintained regardless of weekends or holidays. This opens the door to high-throughput drug screening and large-scale phenotypic studies. Importantly, automation improves the quality of life for researchers themselves. Instead of being tethered to the lab for daily maintenance tasks, scientists can focus their time and creativity on experimental design and data analysis.

Breaking down barriers: What still holds us back?

Despite these advances, significant obstacles remain. One of the largest is the lack of standardised protocols across research groups. Too often, methods are customised to individual labs or even individual researchers, making it difficult to compare results or build upon one another’s work. Long-term culture conditions, often involving multiple people over several months, introduce further variability. Moreover, the field is still missing fully integrated, end-to-end solutions that encompass everything from stem cell culture to organoid differentiation, long-term maintenance, endpoint assays, and data analysis. Without such integration, manual interventions are still required at critical junctures, reintroducing the very variability and bottlenecks we seek to eliminate.

The road ahead

So, what does the future hold? The continued evolution of brain organoid models, combined with increasingly sophisticated automation, promises to accelerate breakthroughs in neurodegenerative disease research. As protocols become more standardised and automated platforms more widely adopted, we will see not only greater reproducibility and scale, but also novel applications – such as personalised drug screening and the study of rare or complex diseases in human-relevant systems.

By making human brain biology more accessible and experimentally tractable, we are expanding the boundaries of what’s possible in both discovery and translational science. The hope is that, with these tools, the next decade will bring us closer to the fundamental goal: understanding, preventing, and treating the devastating diseases that affect millions of people worldwide.

About the author

Dr Felix Spira is senior manager for hardware engineering and applications at Molecular Devices, with deep expertise in 3D biology, microscopy, and automation. He leads international, cross-functional teams and has successfully launched innovative products such as the CellXpress.ai Automated Cell Culture System and a wave-rocking incubator for brain organoids. His career spans both industry and academia, including various roles at Molecular Devices and postdoctoral research at IMBA in Vienna, where he was awarded an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr Spira earned his PhD from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Munich, specialising in systems engineering and advanced microscopy. He brings extensive experience in image analysis, instrumentation, and the development of biological workflows.

Dr Felix Spira is senior manager for hardware engineering and applications at Molecular Devices, with deep expertise in 3D biology, microscopy, and automation. He leads international, cross-functional teams and has successfully launched innovative products such as the CellXpress.ai Automated Cell Culture System and a wave-rocking incubator for brain organoids. His career spans both industry and academia, including various roles at Molecular Devices and postdoctoral research at IMBA in Vienna, where he was awarded an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr Spira earned his PhD from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Munich, specialising in systems engineering and advanced microscopy. He brings extensive experience in image analysis, instrumentation, and the development of biological workflows.