Your health, yourself: Harry’s inherited health

In the fifth part of this series by Ogilvy CommonHealth Worldwide on the quantified-self movement, we meet health freak Harry who, through a genetic testing kit, discovers he has an elevated risk of a heart attack.

(Continued from "Your health, yourself: Dana's daily dose")

Over the course of this series you will be introduced to Thiery, Marta, Claude, Dana and Harry – each of whom (like most of us) have specific health concerns to deal with and / or wellness goals to reach. As both consumers and patients today, they have access to a wide range of personalised technology that promises to smooth their path to wellbeing. But whilst in theory these individualised offerings are more effective than traditional approaches, in reality success is far from guaranteed. It seems that even though health information is readily available at the touch of the button or a swipe of the finger, it is rarely packaged in a way that is truly relevant and meaningful to us as consumers.

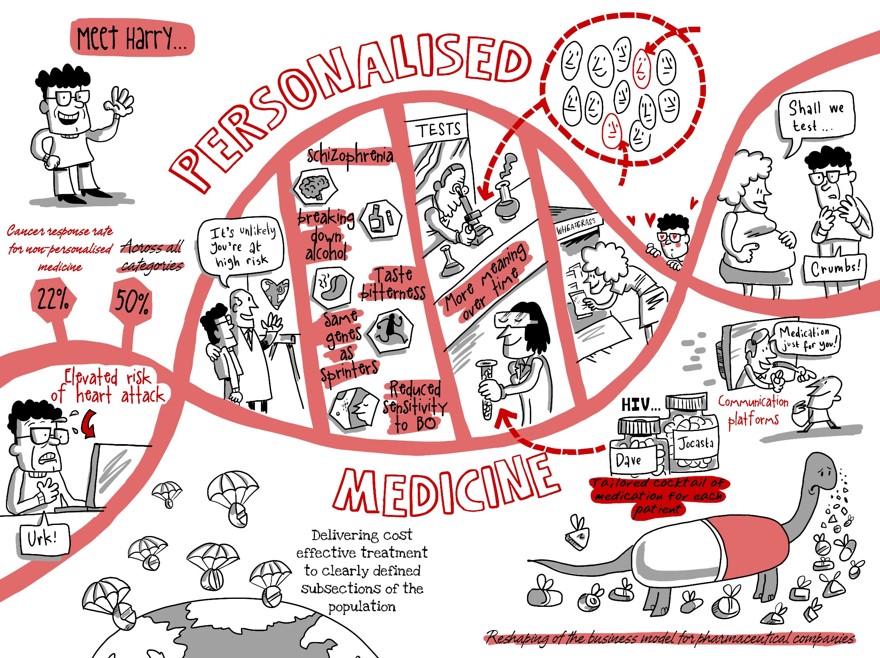

Meet Harry. In fact, chances are you already have. Harry's a bit of a health freak you see. So if you've been to your GP recently, visited a health food store or even logged-on to an Internet health forum or two, probability is you have crossed his path. Being as health focused as he is, Harry is very keen to understand as much as he possibly can about his health and the potential medical conditions he may face in the future. When he found out about the affordable new online DNA testing kits, he couldn't believe his luck. He had always wanted to discover more about his genes and now for a mere hundred dollars, rather than a few thousand, he finally could. He ordered two (just to be sure) and waited patiently for them to spit out his genetic secrets.

"But the journey towards a fully functioning personalised medicine approach has not, and will not, be easy."

When Harry first logged on to see his results, he was distraught. Clicking through to 'My Disease Profile', the first thing he discovered was that he had an 'Elevated Risk' of a heart attack. He was also told that he was at 'slightly higher odds' of schizophrenia and had a reduced ability to break down a toxic by-product of alcohol and cigarette smoke called acetaldehyde. But as he continued reading he relaxed – the information seemed too general to illicit any real concern. Plus, there were a couple of points he quite liked the sound of – he was more likely to taste certain bitter flavours (he didn't realise some people couldn't), shared a genotype with 'many world-class sprinters' and enjoyed a reduced sensitivity to the smell of BO. All in all, Harry thought that wasn't too bad.

Was Harry's test a waste of time? Personalised medicine, defined as the diagnosis and treatment of patients based on their individual characteristics, presents arguably the most important development for medical science and healthcare in recent decades. After all, as Hippocrates once said: "It's far more important to know what person the disease has than what disease the person has." But the journey towards a fully functioning personalised medicine approach has not, and will not, be easy. To date, some of the most promising 'personalised' medications have failed to get regulatory approval, whilst others have not been profitable in the marketplace. It requires large quantities of accurate and segmented patient and population data, without which results are no more insightful than Harry's mail order mess. As his example has shown, the industry still has some way to go before all the results of genetic testing can be usefully applied. But that doesn't mean the test was a waste of time.

Even though physicians currently use all the available and observable evidence they can to make a diagnosis or prescribe a treatment tailored to each individual, current response rates for drugs are still low – averaging 50% across all categories and just 22% in oncology1. Personalised medicine could be the solution for improving these response rates as well as minimising the side effects associated with many therapies.

The encouraging news is that a number of notable success stories already exist. Numerous drugs have been developed for a variety of cancers, including breast and rectal, that can only be prescribed to a subset of patients with tumours that have specific protein markers or gene mutations. This targeted approach has demonstrated impressive results in oncology. And in HIV, physicians regularly prescribe a cocktail of drugs tailored to the genetic subtype of each patient – often extending the life expectancy of the newly diagnosed by 20 to 25 years1. And it is not just the actual diseases that shrivel in the face of targeted, genetic approaches. Personal data also plays a crucial role in the avoidance of treatment side effects. Warfarin, used to prevent blood clots, is now only recommended for specific genetic profiles that are known to respond to the drug – thus avoiding potentially serious consequences. So whilst Harry's do-it-yourself testing kit was not particularly illuminating, the data underlying it are already being put to use in other medically significant ways.

So can Harry expect something more useful tomorrow? What these handful of examples demonstrate is that personalised medicine has a definite future – the only question is how and when. One possibility is that the pharmaceutical industry, who face growing pressure to develop affordable accessible medicines for markets across the world, will use personalised medicine to successfully deliver cost-effective treatments to clearly defined subsections of the population.

Another is that scientists will concentrate their research on the slew of common, chronic diseases like Type II diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity and coronary heart disease that have a significant genetic component. But it is not just new drug development that offers opportunities. R&D departments should also take a second look at drugs which have failed clinical trials due to low efficacy across the general population or dangerous side effects. Are these treatments actually genetically sensitive, with potential to deliver great results to a specific, but significant subgroup of patients?

"...the industry still has some way to go before all the results of genetic testing can be usefully applied."

Of course, as personalised medicine changes the way individuals understand and manage their health, a new set of moral dilemmas will also come into focus. Let's imagine that there really is someone for everyone and even with his obsessive health habits our hapless Harry falls in love and gets married. How does he feel when his wife brings up the question of genetic testing on their unborn child? Harry had been more than happy to send off for his own DNA testing kit and analysis but do the same rules apply for his kid? As the technology becomes increasingly sophisticated and more widely practiced, this is an area of personalised medicine that will affect us all.

What does this all mean for Pharma? Making personalised medicine work will require dramatic changes in pharmaceutical business strategy, including the creation of business models with unfamiliar new capabilities. But the truly forward thinking companies will realise that it is not just what happens deep underground with the hard working scientists in R&D that spells the recipe for success. Since personalised medicine presents such a completely new approach for patients and professionals, it will be how these products and methods are marketed and communicated that really separates the winners from the losers. Brands and companies that wish to profit from personalised medicine will require the development and implementation of clever, connected strategies across the full range of medical communication disciplines. Success will ultimately depend on the ability to demonstrate value to a wide range of demanding stakeholders. This means that payer communications, medical education, expert engagement, PR, brand development and digital strategy will all be critical elements of any intelligent marketing plan.

Finally, traditional mass-marketing approaches will no longer be appropriate for the range of new, individual drugs. Embedded within the fabric of future communications, campaigns will need strategies that enable patients to understand their personal data and treatment pathways. And let's not forget dear Harry. His experience with the online testing kit has left him a little wary of all things DNA, which means it might be time to reach out with that proverbial (organic) carrot and build back a little trust...

Health highlights:

• Personalised medicine has the potential to provide patients with highly effective, targeted treatments whilst reducing risks of dangerous or undesirable side effects.

• The industry has its work cut out in developing a fully functioning approach that brings real added value to patients, professionals and healthcare providers.

Do:

• Support autonomous individuals with tools that give personal control without replacing professional health oversight

• Keep communications friendly, relevant and meaningful

Don't:

• Rely on technology to do all the work. Digital devices need to be accompanied by scientifically sound behavioural support

References

1. Kulkarni A, McGreevy NP. A strategist's guide to personalised medicine. Available at: http://www.strategy-business.com/article/00131?gko=75ee7 (Last accessed May 2013).

The final article in this series will be published next week.

Other articles in this series:-

Your health, yourself: Thiery's technotraining

Your health, yourself: Marta's nutrition mission

Your health, yourself: Claude's case of compliance

Your health, yourself: Dana's daily dose

About the authors:

Beril Koparal is Managing Director of Ogilvy Healthworld Turkey.

Thomas du Plessis is Senior Executive; Strategy & Planning of Ogilvy Healthworld.

Tracey Wood is Managing Director of Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education UK.

Closing thought: How can we better support patients keen to find out their genetic predisposition to diseases?