Transparently opaque: drug list prices versus net prices

Drug price discounting is becoming more frequent and complex as industry and health care systems struggle to balance access and affordability. Leela Barham considers the pros and cons of keeping pricing agreements confidential.

The price of a drug can be controversial. The controversy is not just about how high the price is, but what drives pricing. Another issue is whether that pricing is fair; how much profit should be made from alleviating suffering? And how much does it really cost to bring a drug to market?

Increasingly, though, these debates are happening when everyone knows that the list price is not the ‘real’ price to be paid, but a starting point to be whittled down through pricing and reimbursement processes. Against this backdrop, is it sustainable to keep net prices confidential?

Complex landscape for discounting

Discounting is not a new practice for pharmaceuticals. However, it seems to have become more frequent and complex as both industry and health care systems struggle to balance access and affordability. The rise of managed entry agreements (MEAs) (also known as risk-sharing schemes, performance-based risk sharing agreements, etc) is an indicator of the rise of what will end up being some sort of discount on the list price.

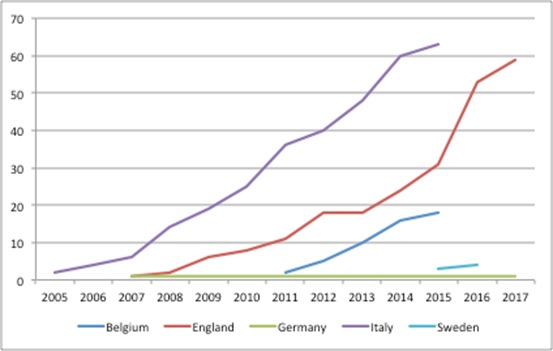

MEAs are particularly popular in cancer, a therapy area where there has been particular push back on prices. Terms used in the media range from ‘outrageous’ to ‘skyrockteting.’ MEAs in oncology in Europe have seen an increase in recent years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The rise of oncology MEAs, selected European countries

Source: Analysis of data sheet 2 from Pauwels, K, Huys, I, Vogler, S, et al. (2017). Managed Entry Agreements for Oncology Drugs: Lessons from the European Experience to Inform the Future. Front Pharmacol. and NICE data.

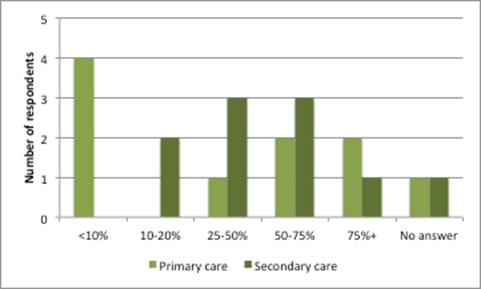

The rise in MEAs also dovetails with results of a confidential survey, conducted in 2016 and published in April 2017, that explored the presence and extent of confidential discounts based on 10 responses from 11 invited countries. The countries included Australia, Austria, Canada, England, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, Scotland, Sweden, the Netherlands and the US. Although a small sample size, the respondents were staff from pricing and reimbursement agencies so should be well informed; collectively, they implied that discounting had been frequent in the last two years. Discounting applied to as much as 75% – or more – of both primary and secondary care products approved for coverage in the previous two years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Frequency of discount use as a share of all patented medicines approved for coverage in the past two years

Source: Data from Morgan, SG, Vogler, S and Wagner, AK. (2017). Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe and Australasia. Health Policy. 121:354-362

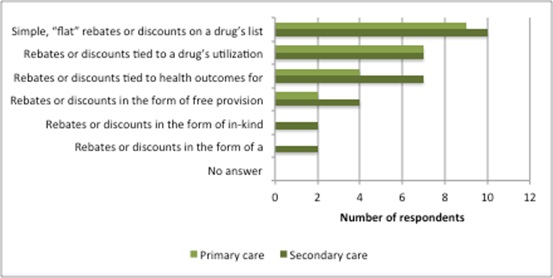

Furthermore, those discounts were delivered through various routes (Figure 3). There are complexities around when the discount will be realised and its scale: it can be linked to volume or performance, or a mix, as the types of MEA range from simple, confidential discounts to money-back guarantees.

Figure 3: Types of discount received in the last two years

Source: Data from Morgan, SG, Vogler, S and Wagner, AK. (2017). Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe and Australasia. Health Policy. 121:354-362.

The difference between list and net price

The rise in MEAs – alongside other discounting methods, such as tenders and mandated discounts as part of legislation covering pricing and reimbursement – means that people know that the list price isn’t the real price. However, with little transparency around discounts, it’s hard to establish the scale of the difference between list and net prices.

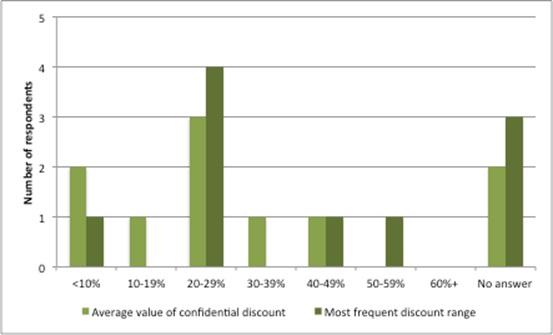

Survey results can only provide an idea (Figure 3). Many of the agreements deliberately ensure that there is no way to work out which countries are getting the best deals or which products are discounted (both companies and payers keep net prices confidential).

Figure 4: Average value and most frequent discount ranges as share of the official ‘list’ prices for the relevant pharmaceuticals

Source: Data from Morgan, SG, Vogler, S and Wagner, AK (2017). Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe and Australasia. Health Policy. 121:354-362.

Tension between transparency and affordability

For companies, keeping net prices confidential can help them to secure returns at a global level, yet also respond to a particular country’s economic circumstances. The argument is that if all countries knew how much their neighbours paid, they would want the same discounts. At the extreme, this would result in a ratcheting down of prices and a corresponding ratcheting down of revenues for the company.

That may sound attractive for payers but, in the longer term, if prices are driven too low – although it’s not clear at what level that would be – the incentives for investing in future drugs diminish and, although it sounds alarmist, could even disappear. That’s bad news for the companies and also bad news when there are still unmet health care needs that could potentially be met through new drugs.

It’s also bad news for payers (and Governments), since among the diseases that don’t have effective (and cost-effective) treatments is dementia, which requires health care, and social care too. That means further expense later.

The downsides of opaque net prices

Despite the arguments in favour of keeping net prices confidential, there are downsides, too. For example, companies have to say that they are pricing responsibly, and hope that people believe them.

In addition, the pricing and reimbursement process is complicated, not only in terms of the transactions costs for different discount schemes, but also regarding how to conduct value assessments of a new drug against another drug that has a confidential discount.

Agencies like the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) have had to amend their approach. Current guidance is that companies whose products are compared to a drug that has a discount through a Patient Access Scheme must run scenarios with discounts on the comparator price in 5% increments. This means more work for the company and less-precise information for SMC to base decisions on.

It also encourages gaming on both sides: companies set a list price expecting to have to give a discount and payers won’t accept the list price, expecting to receive a discount. The net price may be good, but not necessarily great – for either side – depending upon skills of negotiation and each party’s respective information. Leaks of net prices of competitors’ prices are likely to shape the negotiations too. Not an efficient way for the ‘market’ to discover price.

Increasingly, some argue that comparing list prices between countries will be irrelevant and international reference pricing (IRP) less useful to payers. However, it’s likely to continue because it is an easy-to-apply cost containment tool, relatively speaking. A signal for that is the boost to funding given to the EU’s Euripid pricing database, resulting in guidance on best practices on how to conduct external reference pricing. That means companies will simply have to do both: confidential value-based pricing and try to mitigate against IRP.

It also muddles the signals for what kinds of new drugs are needed as a company will only know the net prices for its own products, not for other products in the same therapy area or therapy areas where it’s not active.

How sustainable is opaque pricing?

Although it is only one part of the transparency agenda, getting transparency on net prices is an important aim for some groups. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) cites the varying amounts charged for the same medicines in different countries as an area where transparency is ‘vital’. Also on its transparency wish list, set out in May 2017, is transparency of drug development costs and how prices are set. The industry – as expected – disagrees. The UK’s industry organisation the ABPI responded by saying that ‘sharing of net prices would undermine the industry’s ability to ensure an appropriate price is paid in each context and would likely affect patients’ access to medicines’. So it’s a stalemate.

However, opaque net prices can put industry in a bind. An example is when the US industry association PhRMA criticised the work of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). It said: “ICER should adjust its methodology for calculating ‘provisional health system value’ so it better reflects actual prices for new medicines, and may want to consider waiting for a period of time after a new product is first introduced to permit collection of more accurate price data.” But delay is not an acceptable solution, as decisions can’t be put off. Instead, ICER has said it will use estimates of prices net of rebates, instead of list prices.

The real issue is that, despite good reasons for price discrimination, there is no guarantee that a price set for one country would be limited to that country, if the figure were available publicly. It would rely on every country being a good global citizen. There may also be little trust that companies will approach pricing to achieve a reasonable global return overall, but no more than that.

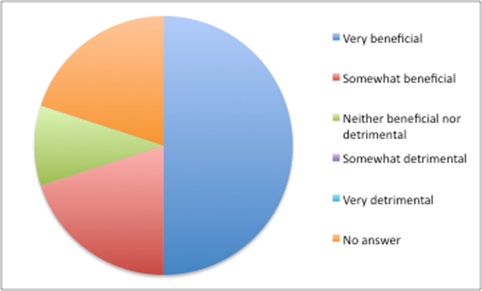

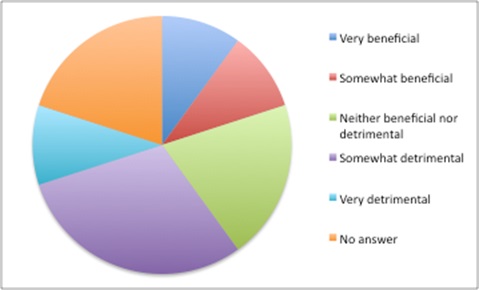

Doing the best for yourself when you can’t rely on others to do the best for all is understandable – akin to the prisoner’s dilemma in game theory – even if everyone would be better off if everyone trusted everyone else to do the ‘right’ thing. The tensions in using opaque prices are felt by payers. They are more likely to say that there are benefits in confidential discounted prices when thinking about their own health system, but are more likely to see them as detrimental when taking the perspective of health systems worldwide (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Views on the benefits of confidential discounted prices when taking the local health system perspective

Source: Data from Morgan, SG, Vogler, S and Wagner, AK. (2017). Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe and Australasia. Health Policy. 121:354-362.

Figure 6: Views on the benefits of confidential discounted prices when taking the worldwide health system perspective

Source: Data from Morgan, SG, Vogler, S and Wagner, AK (2017). Payers’ experiences with confidential pharmaceutical price discounts: A survey of public and statutory health systems in North America, Europe and Australasia. Health Policy. 121:354-362.

Richard Torbett, the ABPI’s Executive Director for Commercial, captured the feeling succinctly at the launch of the Centre for Health Economics & Policy Innovation on 31 May 2017. He told delegates, “We don’t really know what the real prices are that are being transacted. It’s a legitimate debate there about transparency.”

Expect more debate on just how far transparency can go into pricing.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more from Leela Barham in Deep Dive: Oncology: