Rare diseases part 1: posing questions that are difficult to answer

Neil Dickinson

Dice Medical Communications

Opening our rare diseases month, Neil Dickinson shares his views on the orphan drug industry, discussing the changes in legislation over the years and the impact this has had on the rare disease patient community.

The pharmaceutical industry has always been different to most other commercial sectors and almost every point of difference can ultimately be traced back to the fact that we are dealing with people’s lives.

In any other industry, the paying public sees no conflict between technological development and the inventor receiving a generous return on their investment. Nobody seems to begrudge Apple or Dyson their well-earned billions, but try to elicit sympathy for the likes of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) or AstraZeneca (AZ) and you won’t get much sympathy, even when they have created life-saving drugs for cancer, HIV and other diseases.

,

"In any other industry, the paying public sees no conflict between technological development and the inventor receiving a generous return on their investment."

,

It’s almost as if individual pharma companies are expected to be run purely as philanthropic, not-for-profit organisations, where the normal commercial drivers of shareholder and investor returns do not apply.

A rare act of legislative foresight

In recognition of this, Orphan Drug legislation was introduced back in the eighties, because governments and regulators had the foresight to recognise that without a special form of ‘revenue protection’, there would simply be no commercial imperative for the highly innovative R&,D departments of the industry to tackle rarer diseases. After all, development costs for a complex biologic to treat Gaucher Disease were probably just as high (if not higher) as those for something like Lipitor, but with a potential patient population numbered in the low thousands rather than the high millions.

Genuine human impact – a personal story

The result of this legislation was felt by me personally, because in my twenties I married a carrier of Fabry Disease. We knew then that having children was a risk and we just accepted that it was unlikely there would be any credible treatment within our lifetime. It is truly extraordinary to think that in the intervening years, several treatments have been brought to market which have greatly benefited hundreds of patients around the world with this potentially devastating inherited genetic flaw.

The law of unintended consequences

But nothing is ever straightforward in life, is it? The very success of this legislation is bringing modern day consequences to bear on governments and payers around the world and unless the issues are tackled with imagination, it could be a tricky time ahead for pharma companies involved in the rare disease arena. Only recently, the 1000th orphan drug designation was granted to a ‘contender’ in early phase development and while there are ‘only’ 70 orphan drugs currently authorised to treat patients, their cumulative costs are starting to present governments with some difficult decisions.

,

"...treating 50 patients for a rare disease at perhaps £200,000 per annum would pay for a lot of hip replacements..."

,

A simple calculation

It doesn’t take an expert to work out that treating 50 patients for a rare disease at perhaps £200,000 per annum would pay for a lot of hip replacements, or cataracts. This is an argument that has been advanced on many occasions over the years in debates about NHS funding, but the orphan drug market has brought things into much sharper focus. Governments and regulators have neither the wisdom of Solomon nor bottomless pockets at their disposal to solve the problem, so what does the future hold?

The Dice poll

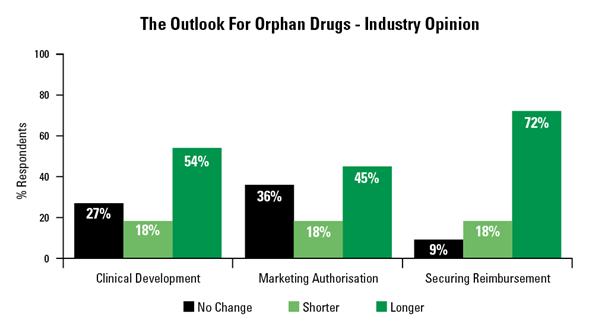

In preparation for this article, we conducted a poll amongst industry specialists in the orphan drug space and their concerns were very consistent. There is definitely a sense that clinical development, marketing authorisation and reimbursement will all take longer in the future.

Figure 1: Bar chart showing the outlook for orphan drugs, from a poll conducted by Dice.

Figure 1: Bar chart showing the outlook for orphan drugs, from a poll conducted by Dice.

But the most emphatic response was the recognition that some form of risk sharing with healthcare commissioners / reimbursement authorities was inevitable in the future: 90% of respondents agreeing with this.

A new age of realism

It’s clear that pharmaceutical companies in the orphan drug space recognise that the competition for scarce resources is becoming more intense and it will no longer be assumed that simply because a rare disease has never been treatable before that the first therapy to come along will be welcomed with open arms.

,

"It would be wrong to assume that the orphan drugs area is full of doom and gloom."

,

A classic example of this was last year’s knock-back of Huntexil® for Huntington’s Disease. This is a patient group desperate for an effective therapy, but the new tougher regulatory regime rejected Neurosearch’s submission, despite evidence of a statistically significant improvement in Total Motor Score.

Is there a need for better presentation?

The pharmaceutical industry does not have a great track record of presenting itself in the best light, but if ever there was a need for some leadership, then the space is rare diseases and the time is now.

“There is a pressing need to explain the purpose and value of the EU Orphan Drug Regulation for patients and wider society. There could be a real backlash from regulators and society as a whole if we don’t explain ourselves clearly.”

Nigel Nichols, UK / Ireland Director at BioMarin, summed up his concerns for the future.

A good story that needs to be told

It would be wrong to assume that the orphan drugs area is full of doom and gloom. On the contrary, it is a very vibrant sector of the industry where innovation is evident from the laboratory right through to the marketing department, but complacency about the future must not be allowed to develop.

Our industry has had a fantastic run for the last century and deserves more accolades than it gets. There are many previously intractable diseases that, in effect, have been or are being controlled or even eradicated. The industry track record in HIV, turning a lethal infection to a very manageable condition from a standing start in less than 30 years, is a staggering achievement. Unfortunately, the man in the street is probably totally unaware of the industry’s role in this great story.

The rare disease sector is full of success stories: hope where none existed before, life when previously death was inevitable. This story needs to be told, otherwise orphan drugs will only be seen in context of their cost and not their value.

Read part two of this article here.

,

About the author:

Neil has worked in pharmaceuticals since the late 1970s, starting out as a research chemist and gravitating towards healthcare communications.

He founded and ran Matthew Poppy Advertising for 15 years before it was bought by WPP.

Neil now runs another specialist agency: Dice Medical Communications, based in Marlow.

Email: neil@dice-comms.co.uk

Website: www.dice-comms.co.uk

Twitter: @DiceDigital

How can pharma raise awareness of its orphan drug success?