Promise for combination approach to cancer

As immuno-oncology increasingly involves more than one agent for best efficacy, market positioning must take a pan-tumour approach, argue Kelly Price and Chetan Taylor.

Kelly Price & Chetan Taylor

Immunotherapy may seem to be the ‘new, new thing’ in the fight against cancer, but actually it’s not: in fact, it may be one of the oldest. In 1890s New York, a leading surgeon, Dr William Coley, was intrigued when he saw complete cancer remission in a patient following two attacks of a bacterial infection. He investigated further, and over a 43-year period he treated almost 900 cancer patients, mostly those with inoperable sarcomas, using weakened bacterial strains which later became known as ‘Coley’s toxin’.

Coley achieved a cure rate of about 10% but, despite this, his methods were not accepted by the wider scientific and clinical communities at the time – probably because of the low cure rate and the severe fever patients had to endure. Instead, when other treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy – treatments targeting the tumour – were developed, Coley’s toxin was all but forgotten. Nevertheless, it was the first hint that the body had the ability to fight off tumours, and that some sort of outside stimulus might provoke the immune system to fight cancer.

Today we have a much greater understanding of the immune system and how it interacts with cancer. In the past few years alone, a whole arsenal of new immunotherapeutic drugs have come on to the market to combat cancer, shifting the focus back to stimulating the immune system to produce an anti-tumour response. There are a number of agents that act in different ways to do so:

- There are drugs to take the brakes off the immune response which cancer cells usually prevent. For instance, Bristol-Myers Squibb’s (BMS) Yervoy (ipilimumab) enables immune cells to induce the proper immune response to cancer cells.

- Drugs that effectively unmask cancer cells to the immune system so they can be identified and destroyed, such as the raft of PD-1/anti-PD-1 drugs targeting other immune checkpoints such as BMS’s Opdivo (nivolumab), Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) or Roche’s atezolizumab.

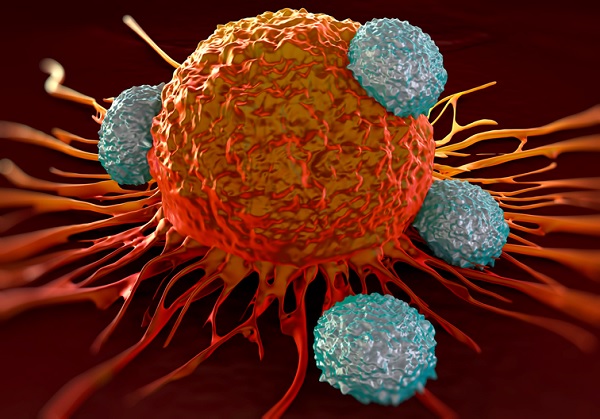

- Additionally, there is great potential for immune cells (T cells) that can be engineered outside the body to target virtually any tumour-associated antigen before being infused back into patients, with promising results. Effectively, this turns T cells into soldiers trained to recognise and assassinate tumour cells.

4-1BB receptors

One of the newest promising innovations in immuno-oncology (IO) drug development centres on agonist antibodies, which stimulate/activate a response from a cell. In this case, 4-1BB receptors on immune cells have been targeted and, once activated, they accelerate the immune response to tumour cells to drive cancer into remission.

Many of the immune cells in the immune system broadly express 4-1BB receptors (e.g. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, B cells, Natural Killer cells and dendritic cells). Stimulating the 4-1BB receptors bolsters the anti-tumour response that may have already been progressing via other IO agents, making it an exciting and impressive weapon in the fight against cancer.

Less is more

Interestingly, 4-1BB agents were almost lost in obscurity, like IO itself, owing to initially disappointing trial results. BMS’s 4-1BB agonist antibody asset urelumab looked promising in phase 1/2 clinical trials, but these were terminated because of incidences of severe (grade IV), potentially fatal, hepatitis in melanoma patients.

Researchers learned that 4-1BB can elicit strong anti-tumour responses across broad cell types, but it can also elicit auto-inflammatory side effects. It turned out that ‘less is more’, because reducing the dose of 4-1BB agonist antibodies administered to patients achieved the desired anti-cancer effect without the hepato-toxicity.

Match-making…

Next came the ‘dating game’: finding further efficacy by ‘coupling’ 4-1BB with other agents. In the rejuvenated development programme of 4-1BB agonist antibodies, physicians noted that, when it was combined with CTLA-4 antibodies like Yervoy, the synergies actually counterbalanced the hepatotoxicity.

This combination approach was reinforced further in late 2015 when Pfizer reported early data of its 4-1BB agonist antibody asset:

- In a trial of 38 advanced lymphoma patients who had received Roche’s Rituxan (another antibody activating the immune system) and Pfizer’s 4-1BB agonist antibody, at least one-third of those with either mantle-cell lymphoma (a particularly aggressive form of lymphoma) or follicular lymphoma showed a reduction in cancer with no serious side effects.

- In fact, one follicular lymphoma patient receiving Pfizer’s 4-1BB asset for two months in the trial has now been cancer-free for three years. Clearly, combining 4-1BB with other agents seemed to be the way forward.

This underlying attitudinal shift in 4-1BB’s resurrection, and its evolution from a monotherapy to an effective combination partner for other IO drugs, is emblematic of the trend to combine forces in IO.

Pan-tumour positioning

Unlike drugs that target the tumour, which may work well in one tumour but almost certainly won’t work across a variety of tumours, IO’s focus on the immune system means that, to some degree, it is more tumour-agnostic. As such, physicians can gain a positive result in one tumour type and then transfer that experience to another tumour type when the product gains an indication for it – an ever-expanding ‘halo effect’. Thus, getting the launch in the first tumour type right is even more critical.

Yet, as drugs begin to traverse indications, it is hard to resist the temptation to position a drug based on its first indication in one tumour type when a successful launch is the desired outcome. Market researchers need to help pharma companies develop resonating, pan-tumour positioning from the start.

This positioning is made all the more challenging given the fact that so many products, like 4-1BB, will be used in combination with other IO products, meaning that companies must position products within regimens. (Good) positioning is based on a marrying of product attributes and unmet needs. However, as IO is rapidly changing the landscape of multiple tumour types simultaneously, for physicians to assess their unmet needs is like trying to pin the tail on a mad donkey.

Challenges are opportunities in disguise, though, and market researchers must devise clever, nimble ways to help clients develop resonating pan-tumour positionings and marketing strategies for their products.

About the authors:

Kelly Price is head of the Oncology Specialist Group at THE PLANNING SHOP international. With a background in strategic consulting, she has over 14 years’ experience in oncology-specific research across the spectrum of tumour types.

Contact her on tel: +1 215 680 8720 or email: kelly.price@planningshopintl.com

Chetan Taylor is a research manager in the Oncology Specialist Group at THE PLANNING SHOP international. He has nearly six years of global pharmaceutical research experience and a background specialising in cancer biology. He joined the company in January 2016 to focus on the oncology sector.

Contact him on email: chetan.taylor@planningshopintl.com

Read more: