Online adverse events: finding pharma’s needle in the electronic haystack

In the second part of this three article series exploring managing online adverse event tracking, Paul Tunnah continues his discussion with IMS Health's Siva Nadarajah, looking into the perception versus reality of this space and how technology is providing solutions.

(Continued from "Pharma experiences side effects from the internet ")

In the previous article, we explored how the regulatory environment is adapting in the face of tackling online adverse event reporting. However, lack of clear regulations on its own is not the major concern for the pharma industry – it is the perceived overwhelming volume of adverse event reports online that cause most concern.

"It is the perceived overwhelming volume of adverse event reports online that cause most concern"

So while monitoring online brand mentions can provide useful information to pharma companies, Siva Nadarajah describes how the "benefit to risk ratio of gathering information from online sources, then using it for marketing intelligence, is perceived to be high on the risk side". In order to test the real scale of online adverse event reporting and challenge this perception, he was involved in a study tracking posts relating to a leading type-II diabetes drug over a 12 month period.1

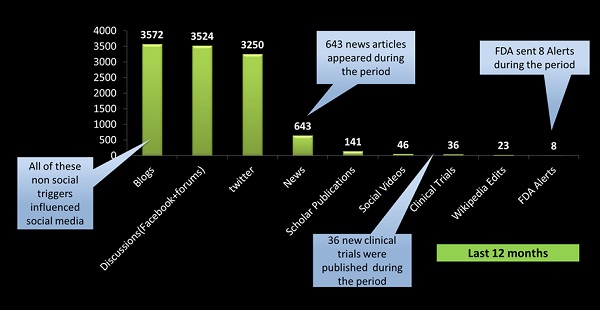

During this time, 11,246 posts were picked up that mentioned the specific drug, which were spread across a variety of sources (figure 1), including blogs, forums, social channels and news alerts. Over the 12 months there were 36 new clinical trials published and eight alerts issued by the FDA. And the volume of reportable adverse events identified from these posts?

Figure 1: Total posts mentioning a specific type-II diabetes drug over a 12 month period and breakdown by channels. 1

Two hundred and eleven – just 1.8% of the total posts. It is a figure that is representative of other studies, says Nadarajah – "you see about 2% of the conversations will have reportable adverse events, pretty much across all disease states". Even if you look for reports that do not meet all criteria, the figure is still relatively low, with typically 7-8% of posts falling into this category that should be tracked, but not reported.

The real challenge, Nadarajah explains, is not therefore the total volume of adverse events, but being able to quickly identify the relatively small number of adverse events from large amounts of data. "The problem for pharma companies has been knowing out of these 10,000 or 100,000 posts which are adverse events. Without the proper technology, someone has to look at all these posts", he explains. An unenviable job for anyone!

The role for technology in managing online adverse events

The solution, Nadarajah believes, lies in using the right technology to quickly and efficiently sift through this enormous volume of data to identify and report adverse events that meet some or all of the regulatory criteria. In order to do this, any technological solution must be able to:

• Interrogate different sources and formats of potentially unstructured data;

• Know what language / key terms to look for when searching for adverse events;

• Allow users to efficiently review the outputs and form links between associated data pieces that individually might not constitute a reportable adverse event.

"You need a new set of taxonomies, a new set of ontologies, which can understand how a patient describes a side effect on Facebook"

Whilst there are numerous tools available now that can rapidly screen online data for specific terms and present the outputs in a user-friendly format, the most complex aspect of this relates to the second point – knowing exactly what language to look for when searching for adverse events. "Here, technology plays a very important role. You need a new set of taxonomies, a new set of ontologies, which can understand how a patient describes a side effect on Facebook, for example. This requires historical data collection, and a very rich dataset that can catch every single description of an adverse event, every single variation of it, misspellings and abbreviations, that people use in social media", Nadarajah elaborates.

Without this rich background data library, derived from historically studying how people talk about side effects online, the analogy is that it is like looking for a needle in a haystack without even knowing what a needle looks like. It is here that most 'non-pharma' technologies fall down and it is a problem that Nadarajah has spent three years focusing on; slowly developing a 'side effects lexicon' for each disease state by observing the conversations of patients, doctors and pharmacists. With this piece in place, the rest of it flows seamlessly. Without it, the downstream process may appear seamless but, like a slick forecasting model with bad data inputs, is fundamentally flawed.

What is really interesting is that the language-driven technology can actually be applied to 'offline' data too, such as market research reports or representative data from a CRM system. "As long as you can process one unstructured dataset you can process any unstructured dataset", Nadarajah explains.

Can adverse event monitoring be totally automated?

Nadarajah is unequivocal in his response to this question. "No. Eighty percent of the work is done by the machine and 20% of the work should be done by the human - we are not going to eliminate the human factor at all." Even with the best natural language processing dictionary and the smartest technology, the process is not perfect. What is important is that the technology is not missing any potential adverse events, but is being overcautious, so human intervention is still needed to review the outputs.

"Managing adverse event reports can be compared to the way in which a doctor manages their patient"

"The human being's job is to eliminate false positives, because the machine is always going to give you some, and ensure the pharmacovigilance department is not being bombarded with too much. But the machine ensures no genuine positives are missed", he explains. So this synergy of adverse event language trained machine and medically trained human allows for an efficient and compliant process that is not overwhelming.

Ultimately, the way in which Nadarajah views managing adverse event reports can be compared to the way in which a doctor manages their patient. The number one rule for a doctor is 'do no harm', which equates to the number one rule for Nadarajah of 'do not miss any adverse events'. But beyond that, it is about optimising the process of managing adverse event reporting, which allows pharma to do the constructive work it really wants to do online, without fear of a call from the regulators.

And with an efficient process for getting rid of those needles in the haystack, pharma can push forward with feeding its research and commercial activities from the wealth of patient and prescriber data that is out there.

References:

1. Knowledgent / Semantelli study, unpublished.

The next part of the series, exploring how social media monitoring will drive greater engagement for pharma, can be viewed here.

About the interviewee:

Siva Nadarajah is Director, Social Media Offerings at IMS Health and joined the organisation through the acquisition of Semantelli, which he co-founded and grew to be an industry recognized leader in social analytics for pharma. Currently he is director of social media offerings at IMS Health.

Prior to founding Semantelli, Siva was responsible for global CRM and compliance solutions with Cegedim. Siva is a voting member of the Wikimedia Foundation and has spoken worldwide about adverse events management in social media and the impact of Wikipedia in healthcare. He was recognized for uncovering two major security holes in Microsoft Hotmail in the early days of the Internet, which forever changed the security design of internet based email systems.

For more information about IMS Health's Social Media Offerings please visit:

www.semantelli.com

How do patients describe adverse events online?