Innovative Medicines Fund and the opportunity for ICSs-industry collaboration to mobilise NICE approvals

In June 2022, NHS England (NHSE) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) launched the Innovative Medicines Fund (IMF). The £340 million fund will provide non-cancer patients access to cutting-edge treatments that still have uncertainties at the time of launch and promotes the UK as an attractive launch destination. The IMF was launched one month before the NHS shifted to a whole system approach, through the formal implementation of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs).

“Any focus on improving patient access to innovative medicines – especially for rare and ultra-rare diseases – is extremely welcome,” said Sean Richardson, VP and general manager UK & Ireland, Alexion during a recent pharmaphorum webinar.

Joining Richardson in an IQVIA-sponsored discussion on the opportunities and challenges of the IMF in the context of the ‘new’ NHS, were: Mohammed Asghar, Associate Director of Pharmacy: Prescribing Governance, Frimley Health; Jay Hamilton, programme director, industry partnerships, Health Innovation Manchester Academic Health Science Network; Angela McFarlane, vice president, strategic planning, Northern Europe, IQVIA; Nina Pinwill, head of commercial operations, NHS England; and Thomas Strong, interim associate director, managed access, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Parity of opportunity for patients

The IMF is a new opportunity for patients outside of the oncology space to access treatments when the evidence base is uncertain, if these treatments have the plausible potential to be cost-effective in time. It builds on the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF), an early access mechanism for many cancer medicines in England.

The opportunity is welcomed by the rare and ultra-rare disease community as their situation remains difficult. A rare disease is defined in the UK as a condition affecting less than 1 in 2000 people, but collectively, rare diseases are not rare. One in 17 people is impacted by a rare disease, yet around 95% of the between 7,000 and 10,000 rare diseases have no effective treatment. Even when treatments are developed, they come with high uncertainty.

“The IMF can help resolve uncertainty. With rare and ultra-rare diseases, uncertainty is magnified. There are small patient numbers, uncertainties in the cost-effectiveness model and clinical pathway and often a lack of comparative data. It’s the perfect storm,” said Richardson.

The IMF is also a positive signal to the industry in a competitive global market for life sciences. “So much has happened in the policy space in rare diseases in the last years, including the IMF. The UK has the ambition to be a life sciences leader. The potential is there,” said Richardson.

Unlocking the promise of the IMF

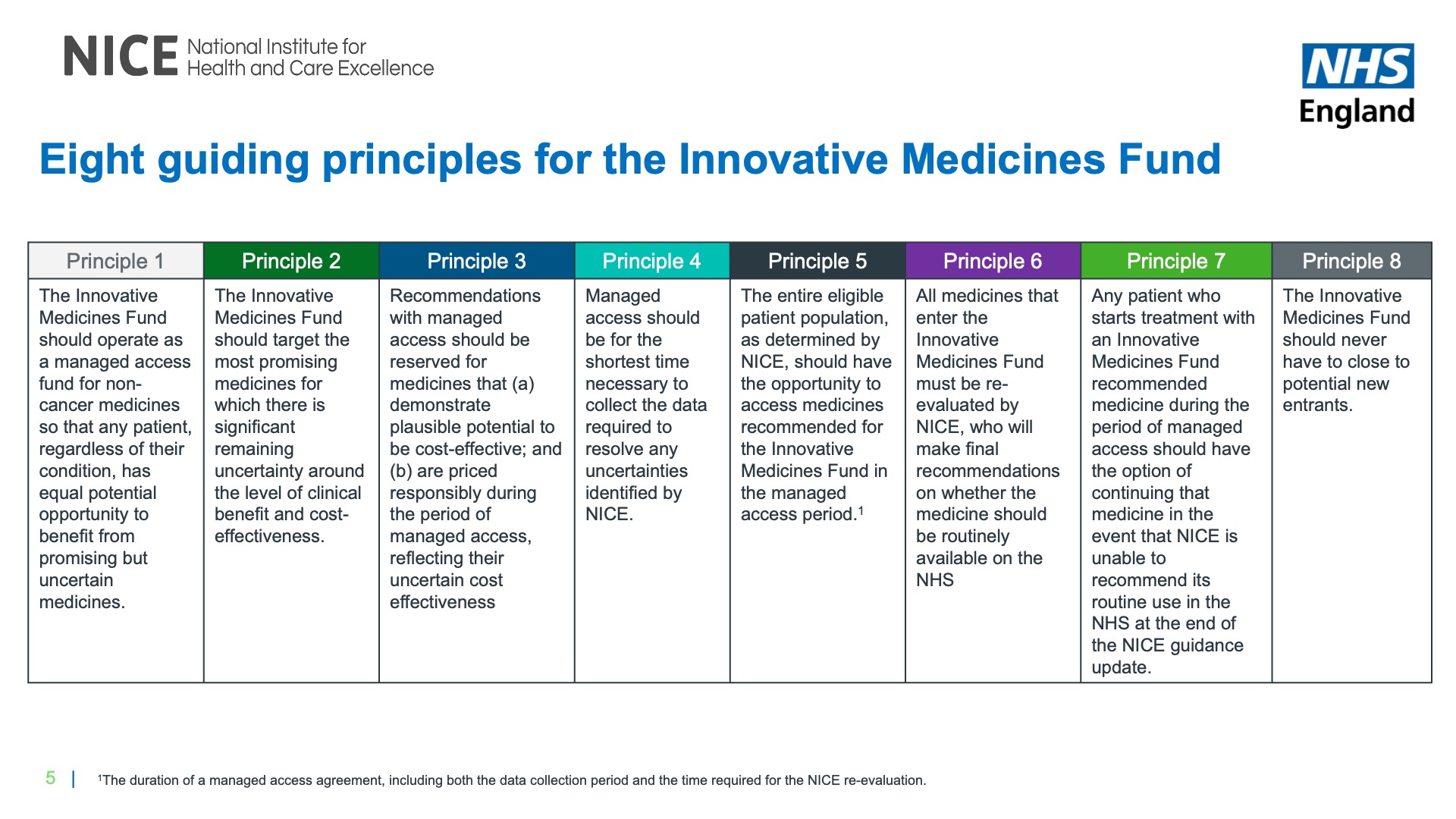

NHSE and NICE have crystalised learnings from the CDF and adapted them for treatments outside of cancer into eight principles for the IMF (Figure 1).  Commercial discussions will be guided by the NHS commercial framework for new medicines. Strong explained, “We now have the commercial framework for new medicines, which means we can have a separate discussion on commercial considerations from the data considerations.”

Commercial discussions will be guided by the NHS commercial framework for new medicines. Strong explained, “We now have the commercial framework for new medicines, which means we can have a separate discussion on commercial considerations from the data considerations.”

Richardson believes the NICE Real World Evidence Framework will help too.

“When you look at all the new technology coming, there is so much heterogeneity, so it’s important that there is flexibility in what sort of data is needed,” Richardson added.

Success of the IMF will come from early engagement and ongoing dialogue. “We want to have conversations with companies as early as possible. It’s also not just one conversation,” said Pinwill. Companies can engage through commercial surgeries at NHSE or through NICE’s scientific advice service and the Office for Market Access (OMA).

A smooth transition to routine commissioning will need NICE to focus on original uncertainties when re-appraising. Richardson said, “I want to put in a plea that when NICE looks again [during the re-appraisal] they don’t open up other uncertainties that were not identified at the beginning.”

Unlocking the potential of the IMF is about the bigger picture, too. Richardson noted, “The IMF could help support delivery of the rare disease framework which prioritises access to specialist care and treatment. I’m delighted that there are so many other policies, such as the Innovative Licensing and Access Pathway (ILAP), but these do need to work altogether.”

There will be challenges too. “Don’t underestimate the cost and resources to implement an agreement,” said Richardson. Those costs are internal and reflect the fees that companies need to pay for at least two NICE appraisals.

The IMF may not be a realistic option for all companies. “There’s a risk, if the treatment is not found to be cost-effective, the company will have to provide the drug in perpetuity. That could be a bridge too far for some,” Richardson pointed out.

Should more than £340 million be needed, companies will collectively need to pay back to keep the budget in check. That could put some off too.

Local uptake through collaboration

More work is needed to achieve uptake at scale and ensure all eligible patients benefit even with a NICE approval, be that recommendation for use via the IMF, CDF or routine commissioning.

“We need system readiness,” said McFarlane. “The issue is landing the medicine in the NHS. Sometimes the runway hasn’t been built, or there are holes in it,” she added. The result can be low and slow uptake. “It can take four years to get uptake. Four years is too long,” she explained.

System readiness is where ICSs come in. “If we have all the right players, the right patient cohorts identified, the right pathway, as well as the positive NICE recommendation and the right price, we can avoid innovations getting stuck,” said Hamilton.

“Innovation is our space,” said Hamilton. “If you, as a life sciences company, are interested in landing a new technology we can orchestrate the conversations and make the roadmap for the industry clear. We are the front door.”

Working with AHSNs can help to prepare the ICSs, yet there’s still work after the NICE recommendation. Asghar reflected on his experience with the uptake of NICE-approved PCSK9 inhibitors to lower cholesterol.

“We did a lot of work locally to look at the pathway,” explained Asghar. “We had two acute provider sites with lipid clinics run by lipidologists, so we decided that they would manage access.”

Data intelligence was crucial to help explore whether this approach to implementation worked. “We looked back six months later. Only one of the sites was delivering in line with expectations,” said Asghar. Knowing that prompted action. “We allowed cardiologists to prescribe too,” Asghar added, “Without data intelligence we would have thought our job was done.”

There is a reality check and an opportunity for industry-NHS collaboration. “When I think about what ICSs need and how the industry can help, it’s data intelligence that is key. We don’t always have the resource for that analysis within the ICSs. It’s a strength that industry can bring,” said Asghar.

ICSs can tackle health inequalities by mobilising NICE approvals

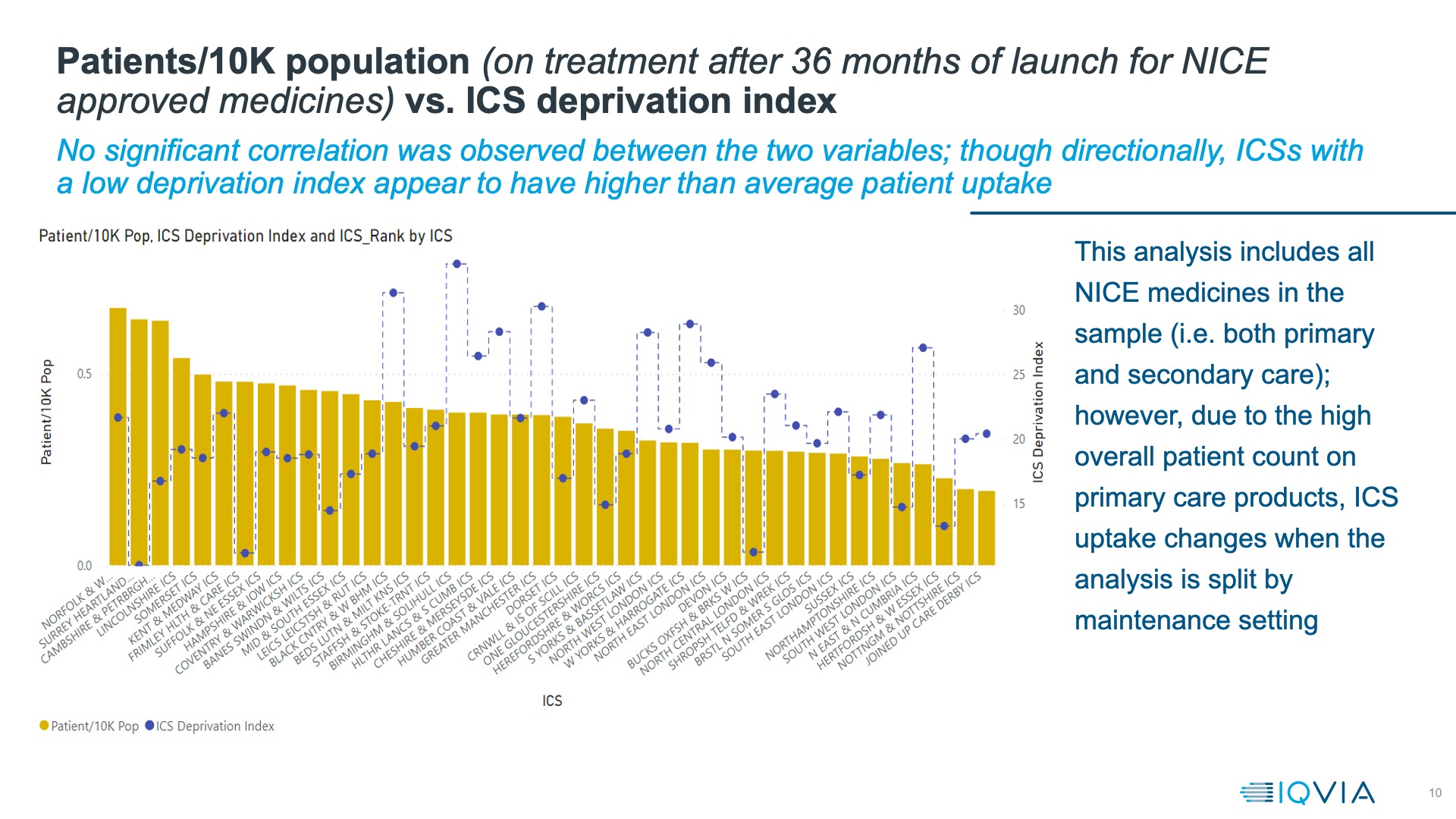

IQVIA has been benchmarking the new ICSs on the uptake of NICE-approved medicines, shedding new light by considering deprivation as well (figure 2). “Our analysis shows that directionally it looks like those ICSs with lower rates of deprivation seem to have higher uptake,” said McFarlane.  That means there is alignment between the objectives of ICSs and better uptake of NICE-approved medicines. Asghar noted, “We have to better join up health and care, improve population health and reduce health inequalities.” Evidence shows that deprivation increases the likelihood of having more than one long-term condition at the same time and the most deprived fifth of the population develop multiple health conditions 10 years earlier than those in the least deprived fifth.

That means there is alignment between the objectives of ICSs and better uptake of NICE-approved medicines. Asghar noted, “We have to better join up health and care, improve population health and reduce health inequalities.” Evidence shows that deprivation increases the likelihood of having more than one long-term condition at the same time and the most deprived fifth of the population develop multiple health conditions 10 years earlier than those in the least deprived fifth.

McFarlane adds, “Some of the perverse incentives with the payer-provider model have theoretically been ironed out. ICSs could be the catalyst for improving local uptake.”

That change in perspective means that savings matter, no matter where they are realised. Asghar explained, “In the past if there was the potential to save on social care down the road, the answer from some would be, we don’t care, we’re only responsible for the drugs budget. But now the stars and planets are gradually aligning to create a much better environment to implement new innovative treatments.”

Block budgets could be a challenge though. Asghar said, “Block contracts can impede the uptake of innovative technologies because they are not actually covered and there is inadequate or no additional contingency funding.”

A one-mission approach to mobilise NICE approvals

Collaboration is key to the success of the IMF and the uptake at scale of NICE-approved treatments.

Industry and others can bring data intelligence expertise, allowing ICSs to identify the right patients for NICE-approved treatments. Next comes the pathway. Even then, uptake is not ‘done’: data intelligence can inform improvements to the runway and ensure the right landing.

Approaching the IMF and uptake of NICE-approved treatments with a ‘one-mission’ approach, panellists agree, is the best way to ensure delivery of the promise of innovative treatments. “We need a one-mission approach, just as we had with COVID. That showed that collaboration can deliver,” McFarlane concluded.

Please contact Manesha Banwait, Marketing Manager, IQVIA if you would like any additional information in relation to the webinar or other IQVIA services.