Healthcare opportunities in Latin America

This first article in a three-part series sets the scene for healthcare trends in Latin America and covers the impact of currency devaluations, corruption and public-private partnerships (PPPs) on the region.

Currency devaluations

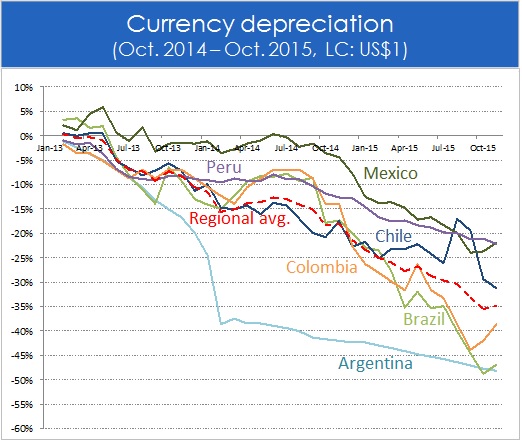

China's shift towards domestic consumption has unfavourably impacted global commodity trading. The currency depreciation experienced throughout Latin America reflects falling demand for exports and is putting the region's long-established dependency on Chinese demand under greater scrutiny (Figure 1). The region's economic stagnation is expected to linger into 2018, with regional economies expected to post only modest GDP growth of less than 3% — well below the robust expansion seen from 2003-2012.

Figure 1. Source: Global Health Intelligence based on data from xe.com

Slow growth and weaker currencies leave the region at a disadvantage with regard to dollar-denominated goods. With the majority of medical devices being imported into Latin America, manufacturers and distributors must revisit their pricing regularly in order to ensure they remain both competitive and profitable. Meanwhile, healthcare systems address cost increases through 'rear-view mirror' budget planning, creating a challenging balancing act. Industry and government institutions are each defending their respective interests, often resulting in a tug-of-war between public spending and cost-cutting initiatives, as was the case with Brazil's healthcare budget throughout 2015.

Though the economic instability of the region will continue to constrain public health systems, Latin America's total healthcare expenditure is expected to reach 7.7% of GDP by 2017. Future growth will depend on the private sector's flexibility and companies' ability to cater to individuals seeking healthcare outside the scope of the public sector.

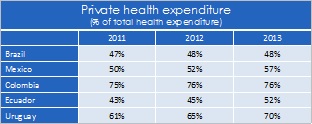

With private expenditure representing 48% and 57% of the Brazilian and Mexican healthcare markets, respectively, these are the largest private markets in which to thrive. Mexico's rebound since its economic slump in 2011 reflects the vitality of the healthcare market. Mexico's healthcare spending grew by nearly 10% in 2012, a direct result of the expanding private sector. Brazil's novel policy change to open private hospitals to foreign investment in 2015 also exemplifies the need for expanded healthcare provision and the role of the private sector in meeting this need. Other countries have also seen strong private sector growth, notably Chile, Argentina, and Nicaragua.

As the second largest and most dynamic medical device manufacturer in Latin America, Mexico is also showing promise. Thanks to its geographical proximity to the US and its lower manufacturing costs, the country has become the fifth-largest exporter of medical devices and remains a tempting choice for mid-sized medical device companies wanting to set up in the region.

Corruption

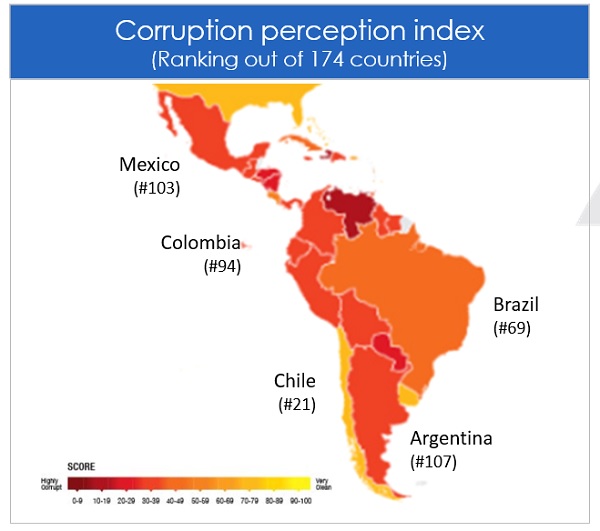

Unethical business practices place a heavy burden on the healthcare systems of Latin America. Theft, bribery and extortion have led to financial losses in the billions. Transparency International's 2014 Corruption Perception Index ranks two-thirds of the region's 31 countries alongside the world's most corrupt nations (see Figure 2). Yet the region can ill afford anything that would further constrain its healthcare system by limiting available resources, lowering the effectiveness and efficiency of services, or lowering quality of care overall. Even though engaging in corruption presents significant risks to companies, with the risk of tarnished reputations and billion-dollar corporate fines among the most severe, it will persist in Latin America.

Figure 2. Source: Transparency International

Much of the corruption stems from political figures and unethical behaviour in the public sector. The prevalence of state-owned or state-controlled healthcare institutions has led to compliance challenges regarding anti-bribery laws.

• In Mexico, kickbacks on government contracts can reach 25-30% of project value in the form of cash and other material goods, such as computers, cars, land, buildings, homes and political favours.

• In Honduras, the vice-president of Congress, Lena Gutierrez, and some of her family were charged with fraud, crimes against public health and falsification of documents. They are suspected of having links to a company that allegedly embezzled the State by selling poor-quality medicine at inflated prices.

• In Guatemala, political corruption in the health system has directly led to loss of life. Authorities arrested 17 people, including the head of the Guatemalan Central Bank, in an ongoing investigation into fraud at the Instituto Guatemalteco de Seguridad Social (IGSS). The scandal reveals that IGSS employees and the head of the Bank of Guatemala stood to make 15% in kickbacks. They have been charged with fraud, bribery, conspiracy, influence-peddling, illegal collection of fees, illicit associations and insider trading. Charges of culpable homicide could be filed as the scandal resulted in the deaths of at least five kidney-failure patients.

Corruption goes beyond bribes and kickbacks. There are many cases of individuals and entities billing the government for services that were never delivered, or even selling expired medications in altered packaging. In Ecuador, such behaviour has become a major issue for the healthcare system. Guayaquil's Teodoro Maldonado Carbo Hospital was one such source of corruption, where dozens of tunnels were used to smuggle medicines out of the hospital for illicit sale.

Even Brazil's image was stained by corruption, with the Petrobras scandal, involving both public and private individuals in a multi-million dollar affair that appears to lead as high as the Presidential Office.

Impunity at the top enables corruption to flourish. As new leaders take office, they have an opportunity to change long-established practices. They must look towards anti-corruption initiatives to reduce the impact of unethical behaviour in the region. The priority for improving healthcare management systems is to increase transparency. There is an opportunity for international agencies and society to come together in the fight against corruption.

• One example is The World Bank, which assists countries in appointing high-profile committees to investigate the scale and scope of corruption in societies, to set priorities for anti-corruption activities, and to develop and implement action plans. These action plans are only effective in conjunction with high-level political assistance and when they involve the public and media.

• Organisations such as Transparency International can empower citizens to take action and hold politicians accountable for unethical government acts. Regional workshops have helped concerned citizens to combat corruption.

Transparency and accountability must increase if corruption is to diminish.

Budget crunch: healthcare gaps to fill

As they strive to provide healthcare to large populations with vast income disparities, Latin American governments struggle with the tradeoffs between accessibility and quality of care. Brazil, for instance, possesses some of the region's most renowned healthcare institutions, but the majority of its public healthcare system suffers from poor planning and understaffing. Most Brazilians complain of long waiting times in the public system.

Mexico also faces a lack of public-private partnerships and poor distribution of resources – public institutions often overlap by geography and unnecessarily duplicate services; they also have yet to reach a consensus on patient portability. These legacy systems fall well short of addressing the growing healthcare pressures of an ageing population.

The lack of infrastructure and misallocation of resources nevertheless offer opportunities for the private sector, especially in countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Colombia, where healthcare expenditure is rising. Companies which can offer high-quality care and treatment at a reasonable cost stand to make significant gains (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Source: The World Bank

However, private sector providers face challenges of their own. Those in Mexico, for example, face a shortage of nurses because they offer lower wages and benefits compared to the pay on offer in the public sector.

While there is no perfect solution, governments can set the stage for private companies to complement and, in some cases, offset rigid and slow public health systems. Rules and regulations will need to evolve as a result, and already some countries have set up new frameworks to enable greater private participation in healthcare provision. Encouraging local solutions and alternatives to imports is particularly relevant given weakening currencies and the grim economic outlook expected until 2018.

• Leading this trend is Brazil where, in early 2015, President Roussef announced that foreign companies could invest in private hospitals, thus helping to expand private care and shifting part of the financial burden away from the public sector. Private equity funds Carlyle Group and GIC Holdings invested over $600 million in the Rede D'Or São Luiz hospital chain to construct new hospitals and expand current facilities.

• International Finance Corporation (IFC) recently helped expand Brazil's outpatient service centres for its third-largest diagnostic imaging company and has also provided telemedicine services to Colombians in remote areas.

• Management Sciences for Health (MSH) received funding to provide technical assistance to Mexico, Nicaragua, Honduras and other countries throughout the region to increase access to integrated health services.

• Telemedicine gained traction in Argentina throughout 2015. Through the recently-launched National CyberHealth Plan, Argentina is developing a connected network of hospitals. The country is taking advantage of this new infrastructure to pioneer new technologies such as tele-ultrasounds and tele-resonance scans. Private companies like Philips are investing in this field by expanding the number of Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS), a remote-radiology service, in Brazil and introducing them into Argentina.

These initiatives, though principally driven by cost-efficiency concerns, also reveal a desire to transition towards a cloud-based framework and patient-centric healthcare. Suppliers involved with connectivity, health IT and diagnostic imaging will be able to capitalise on regional trends to expand in these fields. Private institutions, in turn, are expected to step in and complement the public sector's shortcomings with offerings geared to 'middle-market consumers' – products and services geared to those who want access to better healthcare at reasonable cost.

For a full list of references please contact the author.

The second part of this series will investigate the main burdens faced by Latin American economies – ageing populations, chronic diseases and obesity.

About the author:

Guillaume Corpart is managing director of Global Health Intelligence and a veteran of market intelligence in emerging markets. Global Health Intelligence has the world's largest hospital demographics database in emerging markets and helps companies succeed in their growth strategies. For more information contact: gc@globalhealthintelligence.com

Read more from Guillaume Corpart: