Calls to end the silent epidemic of PTHP

Raising awareness of the risk of post-traumatic hypopituitarism following a head injury must be increased among healthcare professionals, say campaigners.

Thousands of people, in the UK alone, could be suffering from a relatively unknown, but far from uncommon, condition known as post-traumatic hypopituitarism (PTHP), which can leave people experiencing devastating and wide-ranging hormone problems for years on end with no diagnosis.

The condition, though easily and cheaply treated, often remains undiagnosed because of the low awareness of PTHP in the medical community among both GPs and specialists. “This,” said Professor Chris Thompson, of Beaumont Hospital Dublin, “stems from the fact that endocrinologists are not part of the multidisciplinary team caring for patients after a head injury. In addition, within the primary care sector, the symptoms of PTHP can be very non-specific and therefore difficult to diagnose – often surfacing years later.”

This is the reason behind a campaign to ensure NICE guidance states all patients with head injury who present at A&E – and those who go to their GP with symptoms post-head injury –are routinely assessed for PTHP.

In the UK alone, the incidence of PTHP is put at between 18,000 and 30,000 people every year. But this is probably just the tip of the iceberg, with around 1 million people attending A&E for head injury annually and some studies suggesting even minor concussion or repeated small impacts could damage the pituitary gland.

“PTHP is a silent epidemic that is associated with a considerable burden of disabilities,” stated Joanna Lane, author of Mother of a Suicide: The Battle for Truth Behind a Mental Health Cover Up, a book she wrote about her son’s depression and death.

“A substantial percentage of adult acute head injury survivors experience endocrine dysfunctions, yet a diagnosis of hypopituitarism is often not made until months, or even years, later. That this is a problem is undisputed; it now needs to be publicly recognised and urgently addressed during routine follow up protocols,” she went on.

Although NICE had said it would consider including PTHP in its guidance to the NHS previously – warning of the likely symptoms of the condition, including impotence, loss of libido, depression and infertility – when the guidance was published in spring 2014, there was no mention of the issue.

“It is critical that we start to look at the holistic picture following head injury,” added Thompson. “With 20-25% of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury patients suffering pituitary damage, the impact on endocrine function is crucial, and the likely health burden and societal costs of these missing diagnoses are substantial.”

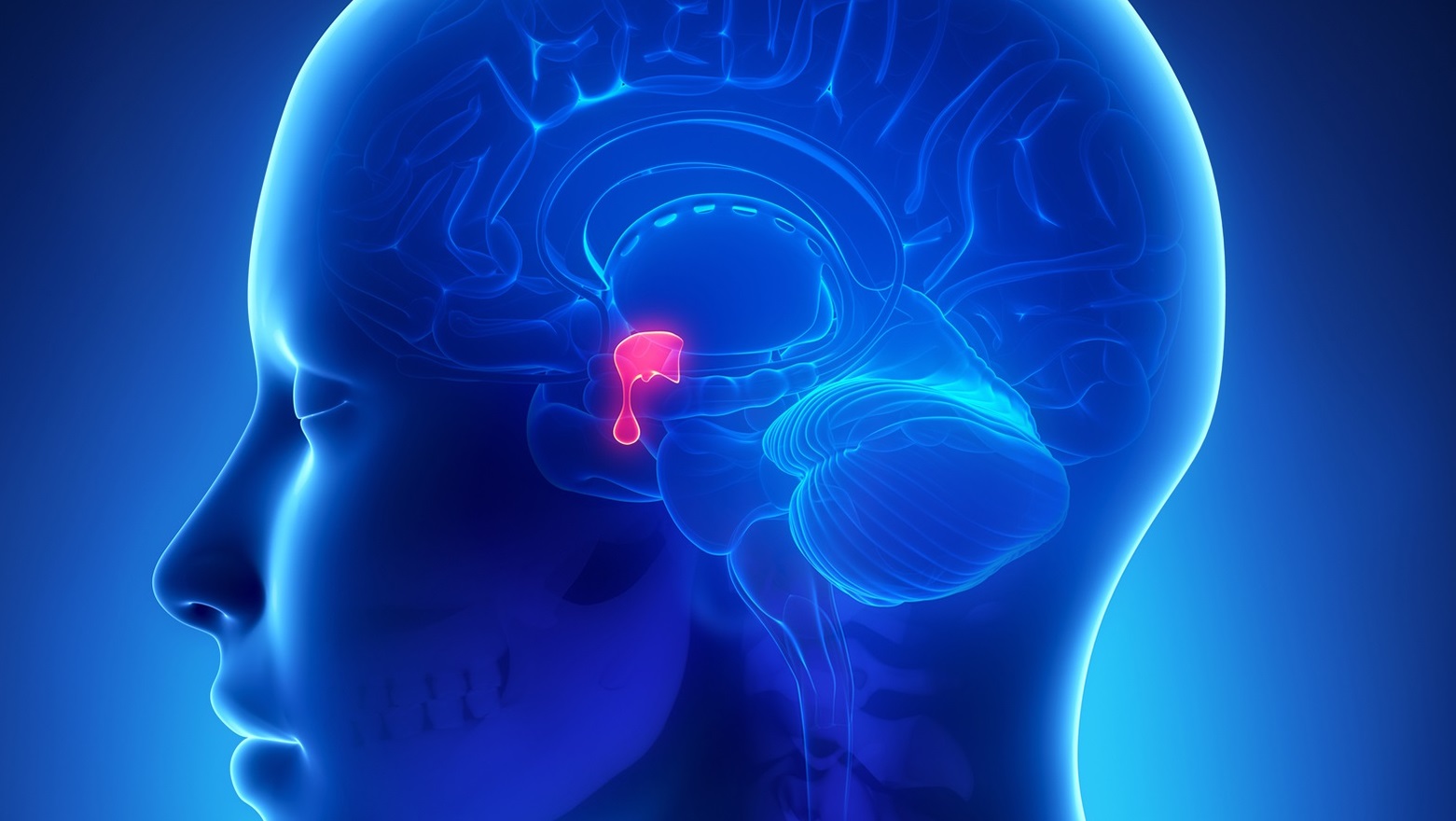

Damage to the pituitary – a pea-sized gland located behind the bridge of the nose – results in a malfunctioning of one or all of the hormones it produces, causing a host of wide-ranging symptoms that vary depending on the severity of the injury.

“Failure to make the right diagnosis after such injury means patients miss out on essential treatment,” Thompson pointed out. Not only are patients not being accurately diagnosed, in many cases they are frequently misdiagnosed because the symptoms produced can be attributed to a spectrum of other conditions, including depression, ME and stress.

This would be easily remedied if there were more awareness of PTHP among GPs and the general public, and if head injury patients underwent routine screening. “Although there is no definitive blood test for PTHP – and the implications of routine screening are potentially substantial – the cost of treatment is low and the impact on the individual is dramatic,” Thompson concluded. “That it’s not included in NICE guidelines is nonsensical.”

More information: http://www.headinjuryhypo.org.uk/index.html

About the author:

Claire Bowie is Head of Publishing at pharmaphorum. She has extensive experience in healthcare communications and publishing, supported by a background in biological sciences.

Read more from Claire Bowie: