Digital health round-up: Bupa latest health insurer to adopt it

Health insurance companies are catching on to the opportunities offered by digital health – and the latest to do so is Bupa, which has signed a strategic partnership with HealthTap to provide a combination of digital and in-person healthcare.

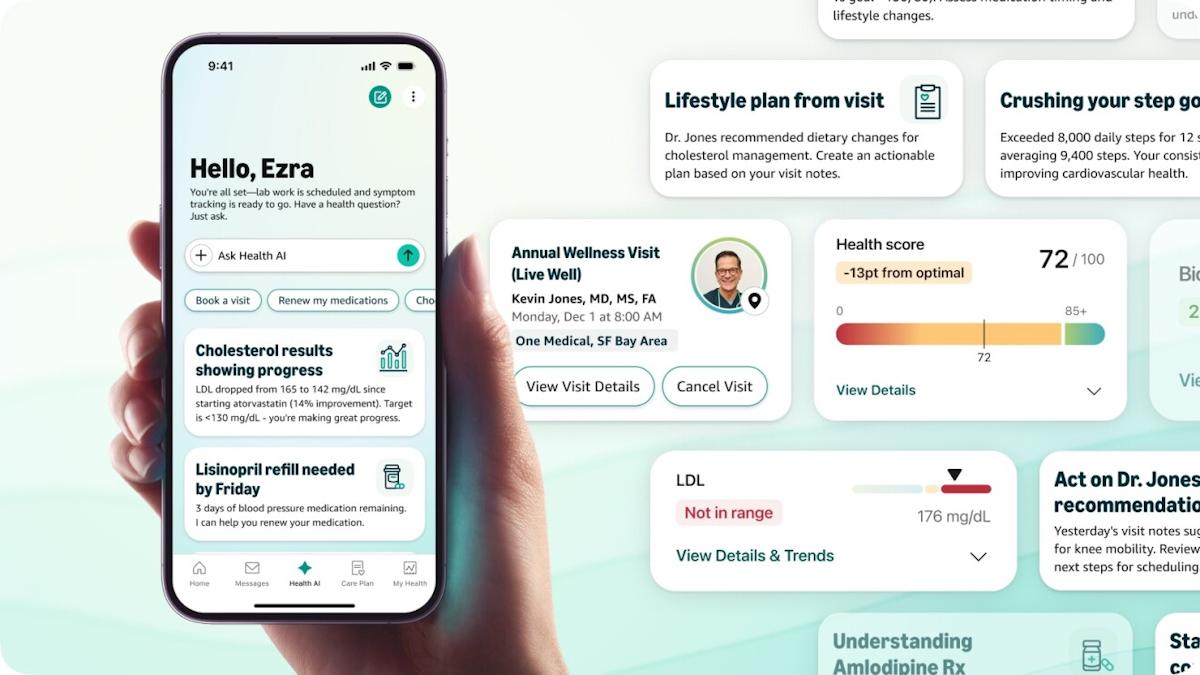

The companies said that the services on offer will be “game-changing”, backed by HealthTap’s ‘Health Operating System’, powered by a network of interactive doctors and artificial intelligence.

Bupa and HealthTap hope the applications on offer through the partnership will enhance the speed, convenience and quality of care for Bupa customers.

No financial details of the partnership were revealed, but the companies said that over the past year they have been working towards a number of solutions for day-to-day customer needs.

These include easily finding doctors covered by Bupa insurance, scheduling physiotherapy, immunisations and doctor visits with local clinics.

Bupa has 16.5 million health insurance customers, and provides healthcare for 10.6 million people in clinics and hospitals worldwide, and looks after around 22,000 aged care residents.

Earlier this month, CareFirst, the largest health insurer in America’s mid-Atlantic region signed a four-year contract with digital health firm Sharecare, to provide members with wellness and disease management services.

AI-based blood test could revolutionise cancer diagnosis

A new artificial intelligence-based blood test can identify eight common cancers by detecting the mutated DNA and proteins emitted by tumours – an approach that could reduce reliance on cancer drugs and allow disease to be treated by surgery alone.

The scientists from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, say the research lays the foundation for a single blood test for cancers of many types.

It opens the tantalising possibility of being able to detect cancers early using blood tests, although at the moment the system is limited to ovary, liver, oesophagus, pancreas, stomach, colorectal, lung and breast cancer.

The new test, CancerSEEK, measures circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) from 16 genes as well as eight protein biomarkers, then uses machine-based learning to analyse the data.

Overall, the test found around 70% of cancers, and five of the eight cancers investigated have no screening programmes for early detection.

Early detection could mean that doctors would be able to intervene sooner to remove tumours, before they spread, according to a report published online in the journal Science.

Although the system is a long way from the market, corresponding author Anne Marie Lennon told Medscape that the test could detect some cancers “early enough that they could be cured by surgery alone”.

Even those that could not be cured by surgery would probably respond better to drugs when disease was less advanced, said Lennon.

Each test is likely to cost under $500, less expensive than current screening tests such as colonoscopy and mammography.

CancerSEEK is now being trialled in people who have not been diagnosed with cancer.

Biosensors

The idea that wearable biosensors could help revolutionise healthcare by providing real-world data has been around for a while – but proof that they help patients is yet to emerge.

A new study by investigators from Los Angeles’ Cedars-Sinai Hospital, writing in the Nature journal, npj Digital Medicine, conducted a literature analysis and found that remote patient monitoring with these sensors had no statistically significant impact on any of six clinical outcomes studied: body mass index, weight, waist circumference, body fat percentage, systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Led by senior author Brennan Spiegel, the study found these devices had shown promise in improving outcomes for conditions such as COPD, Parkinson’s disease, hypertension and low back pain.

But Spiegel said: “As of now, we don’t have enough evidence that they consistently change clinical outcomes in a meaningful way.”

Investigators conducted a statistical analysis and in-depth literature review of 27 studies from 13 countries published between January 2000 and October 2016. Each study examined the effects of remote patient monitoring using wearable biosensors.

The interventions targeted patients who were overweight or suffering from heart disease, lung disease, chronic pain, stroke or Parkinson’s.

The devices studied included physical activity trackers, blood pressure monitors, electrocardiograms, electronic weight scales, accelerometers (devices measuring acceleration) and pulse oximeters (oxygen saturation monitors), among others. These devices were embedded in everything from watches and belts to skin patches and textiles.

A statistical analysis revealed that remote patient monitoring resulted in no significant impact on any of the reported clinical outcomes.

Certain types of interventions worked best, including efforts grounded in social science models and established care guidelines and those that used personalised coaching.

Authors concluded that there was a lack of data from study evidence provided so far.

Of more than 4,000 studies that the authors initially reviewed, fewer than 1% were eligible to be included in the study, and only 16 were considered high-quality research. The authors found very few randomised controlled trials for each of the clinical outcomes analysed, and studies varied significantly in terms of the types of devices used, the populations studied and the interventions tested.

“Many of the studies we reviewed were still in the pilot phase,” said lead author Benjamin Noah, a clinical research associate at the Center for Outcomes Research and Education. “There just is not enough data yet.”

More robust trials are likely to be on their way, however, as many pharmaceutical companies are now exploring their use in proof-of-concept trials.

Could Babylon’s ‘online doctor’ service be delayed?

In the UK a national NHS roll-out of an ‘online doctor’ service outside of London may be delayed while it is further evaluated, according to documents that have surfaced online.

Babylon Healthcare, which produces the service, GP at Hand, has been given full NHS approval to operate in London.

The system is free to use to NHS patients, although signing up to the service does mean patients cannot continue to use their previous ‘bricks and mortar’ GP service.

Babylon already provides nationwide paid-for online GP consultations 24 hours a day, seven days a week in the UK, but its NHS version is the one which could make a big impact.

But a review of the service by Hammersmith and Fulham Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), published in October, which surfaced in a press report, showed that there are teething problems.

Clinical staff who reviewed GP at Hand concluded that it does have potential to benefit the wider healthcare system.

Babylon has denied that its expansion will be delayed by these concerns about its safety, clinical governance, and capacity to support more patients.

The report from the London CCG adds to doubts about the service.

In December, it emerged that NHS safety and quality watchdog the Care Quality Commission (CQC) found Babylon wasn’t providing a safe service in relation to prescribing regulations and best practice.

The report only became public after Babylon tried, and failed, to gain a legal injunction to block it.

Nevertheless, the service has proved popular with some patients, with more than 10,000 joining since its launch, the vast majority being in the 20-44 age group.

A spokesperson for Babylon Healthcare said that GP at Hand is going “from strength to strength” and noted that at a November meeting the CCG accepted the review and its recommendations, and has proposed mitigating actions and a “revised rollout model” that addresses the concerns.