Stem cell transplant eradicates HIV in second patient

A second man with HIV has been cured of the infection after receiving a transplant of stem cells from a donor who has an HIV resistance mutation.

The London patient – who revealed his identity as Adam Castillejo yesterday and has been living with HIV since 2003 – received the transplant after being diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML) in 2012.

30 months after coming off antiretroviral therapy (ART) to suppress HIV, he remains free of the virus, according to an update published in The Lancet HIV today and presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Boston.

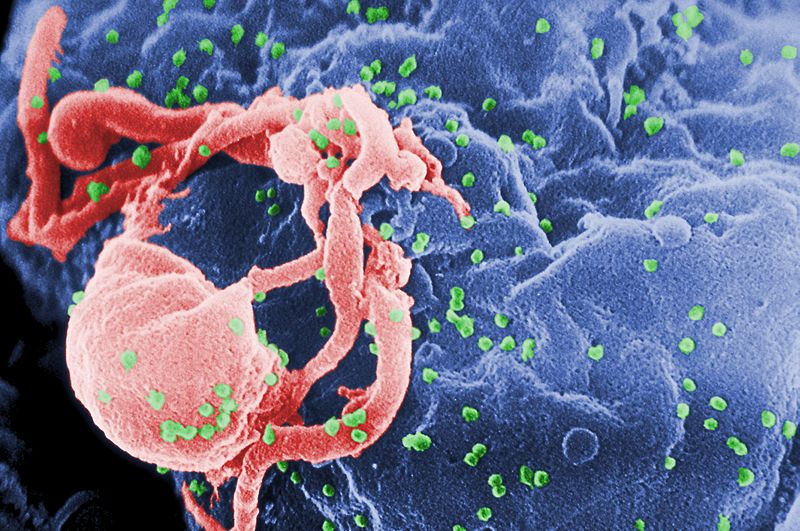

The key to eradicating the virus was the selection of a stem cell donor whose cells had two copies of the CCR5Δ32 mutation that prevents the infiltration of HIV into host white blood cells, according to the researchers.

18-month data from Castillejo’s treatment was reported last year, at which point he was judged to be in remission as it was too soon to talk about a cure.

It’s the first time that the approach which led to the eradication of HIV in Berlin patient Timothy Brown nine years ago has been reproduced clinically, according to lead study author Professor Ravindra Kumar Gupta of the University of Cambridge.

That’s not to say this could be rolled out as a routine treatment, particularly for patients already controlling their infection with ART, as stem cell transplantation is a risky medical procedure that carries a risk of death.

“It is important to note that this curative treatment is…only used as a last resort for patients with HIV who also have life-threatening haematological malignancies,” said Prof Gupta. “This is not a treatment that would be offered widely to patients with HIV.”

Having a second functional cure of HIV does however provide insight into how a more widely applicable cure might be developed in the future, for example using gene-editing drugs to introduce CCR5Δ32 mutation into patients, according to the researchers.

Importantly, Castillejo had a less intensive treatment procedure than the Berlin patient, with a gentler chemotherapy regimen – without whole body irradiation – and a single transplant procedure.

The Berlin patient had two transplants, as well as high-dose chemo and radiotherapy to target any residual HIV in tissue reservoirs.

In Castillejo’s case remnants of integrated HIV-1 DNA remained in tissue samples, but the researchers think these are “fossils” – incapable of reproducing the virus. He will however need continued, but much less frequent, monitoring for re-emergence of the virus.

“There are still many ethical and technical barriers – e.g. gene editing efficiency and robust safety data – to overcome before any approach using CCR5 gene editing can be considered as a scalable cure strategy for HIV,” said co-author Dr Dimitra Peppa of the University of Oxford.

Targeting CCR5 with gene-editing is a controversial topic following the infamous case of Chinese doctor He Jiankui, who modified the genes of twin babies using CRISPR, sparking a backlash from the scientific community. He was sentenced to prison in December for three years after being convicted of conducting illegal medical practices.

Within the sphere of ethical research, gene-editing specialist Sangamo has an early clinical-stage programme looking at editing autologous (patient-derived) stem cells and T cells to carry the CCR5Δ32 mutation.

Meanwhile, Chinese researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine last year that an HIV-positive man treated with CRISPR-edited donor stem cells for a blood cancer had tolerated the therapy well, although it appeared to be ineffective at controlling the virus.