The UK general election: what pharma wants

Funding for the NHS is a key issue for the pharma industry as the UK election approaches. Leela Barham examines how the main parties measure up.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry’s (ABPI) 2017 Manifesto Securing the opportunity for UK life sciences by 2022 sets out what the UK pharma industry wants from the new Government following next week’s UK election. In essence, there are three requests:

- Securing a world-class NHS for patients

- Securing global investment and jobs

- Securing a new relationship with the EU that prioritises patient and public health

They are all big asks, but the first is easiest to measure to determine whether the industry gets its wish. Alongside measuring patient access, it asks the post-8 June 2017 Government to increase health care investment to the G7 average.

This request for more money highlights the long-standing debate over how much should be invested in the NHS as a whole. Not enough funding for the NHS always translates into not enough funding for medicines, although enough funding for the NHS may not always translate into enough funding for medicines, at least from the industry’s perspective.

UK health care spending in an international context

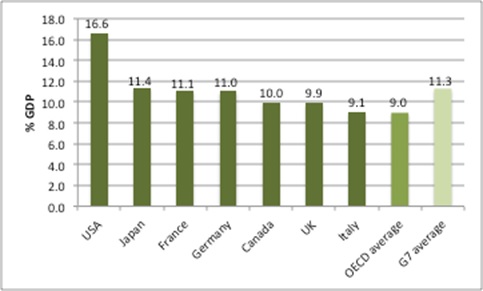

The ABPI draws on figures from the official UK agency, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to back its claim that only Italy among the G7 countries spent less as a share of GDP on health in 2014 (Figure 1). The UK does, however, spend more than the OECD average.

Figure 1: Spending on health care as a share of GDP, G7 2014

Source: ONS

From spending on health to spending on medicines

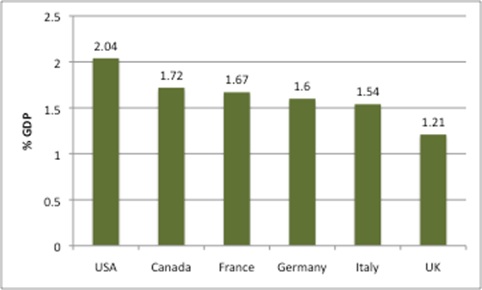

A review of spending on pharmaceuticals shows why the ABPI launched its call; all the other G7 countries (with the exception of Japan, which isn’t included in OECD data) spent more than the UK on pharmaceuticals in 2014 (Figure 2). Presumably the logic behind the ABPI’s request is that, as funds for health rise, so, too, should spend on medicines. In fairness, it’s not just self-interest as many others are calling for more to be spent on the NHS – although they may not want extra funding to go to medicines.

Figure 2: Spending on pharmaceuticals as a share of GDP, G7 2014

Source: OECD

Why the G7?

But is the average health spend of the G7 even the right goal? It is an informal group of major advanced economies and it is natural to want to compare like with like.

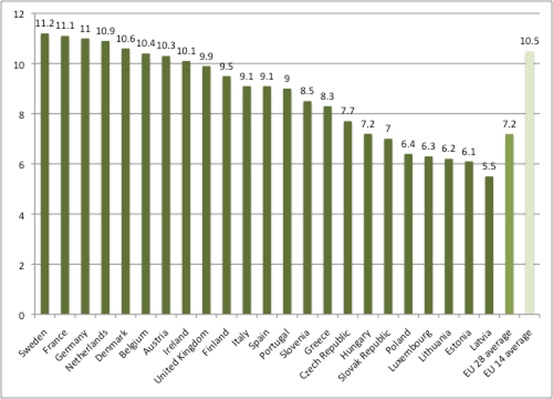

However, other country groupings have been used to compare health spend. In 2000, the then UK Prime Minister, Tony Blair, committed to increase spending on health to the European average. A different basket of countries almost always guarantees a different spending target (arguably even more so as countries join the European Union and, these days, leave too).

Examining the 14 countries in the EU in 2000 and their spend in 2014 results in a target of 10.5% of GDP; taking the 28 Member States results in a target of 7.2% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Spending on health care as a share of GDP, Europe 2014

Source: OECD and calculations using OECD data

Aside from the decision on which countries to compare comes the hard issue of economics: do the countries that spend more, get more? There is some evidence that spending more does indeed get more – and that can include spending on medicines too – with analysis comparing US spend on cancer care to that in Europe finding that not only was spend higher in the US, but increased survival generated value worth $598 billion. At the same time, the US is routinely cited as far less efficient than other systems, including that of the UK.

Politics has a role to play too. In some countries it is a vote winner to prioritise health – as in the UK. In other countries, the opposite is true. The millions who stand to lose health insurance in the US as ObamaCare is rolled back is a case in point.

What would the UK need to spend to reach the G7 average spend on health care?

Accepting that the G7 is the right group for comparison, how much would the UK need to spend to hit the G7 average on health care? Using the 2014 figures and applying the G7 simple average of 11.3% of GDP, the UK would have had to increase spending on healthcare by £25.5 billion in that one year alone.

The increase rests on all sources of funding for healthcare, though; the UK can only hit the 9.9% that the ONS cites thanks to a 2% uplift as a result of private/voluntary spending. There is no reason to think that the private/voluntary spend would be increased easily. If Labour wins the UK election it intends to increase the tax on private medical insurance. If Government had to make up the 2% of the private/voluntary spend to hit the G7 average, it would increase the gap to be filled to closer to £62 billion.

UK Election commitments: nowhere near the investment needed to reach the G7 spend on health care by 2022/23

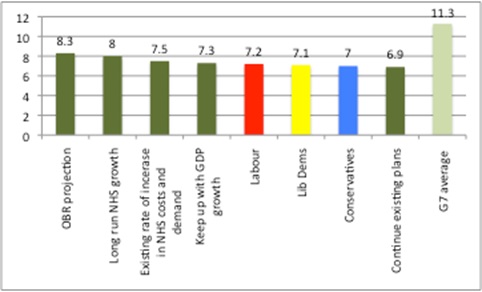

The Nuffield Trust has done the number crunching on how the three main political parties compare on their promises for funding the NHS in England (note that the baseline is different, with 7.3% being the share of GDP for spending on the NHS in England versus 9.9% from the ONS international comparison). Nuffield’s estimates put the potential spend at between 7% and 7.2% of GDP by 2022/23 (Figure 4).

All the parties’ commitments fall short, from keeping pace with GDP growth through to Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projection. It is only when the parties’ commitments are compared to the existing plans that any of them look good. The commitments fall considerably short of the ABPI ambition, even taking the G7 average spend as it was in 2014 (which will probably change by 2022/23, and upwards, not downwards) and knocking a couple of percentage points off to account for England only.

That the ABPI is ambitious in it’s call doesn’t diminish the importance of industry lending its voice to those of others who say that investing in the NHS is a key issue for debate.

Figure 4: Predictions for the share of GDP on health care in the UK by 2022/23

Source: Nuffield Trust and calculations using OECD data

No-one can take spending commitments at face value, partly because the Conservatives promised £8 billion for the NHS by 2020. It turned out to be £4.5 billion because of other cuts. The ABPI may do well to get two of its three requests, as to achieve three out of three is highly unlikely.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more from Leela Barham: