AI-backed blood test could reduce reliance on cancer drugs

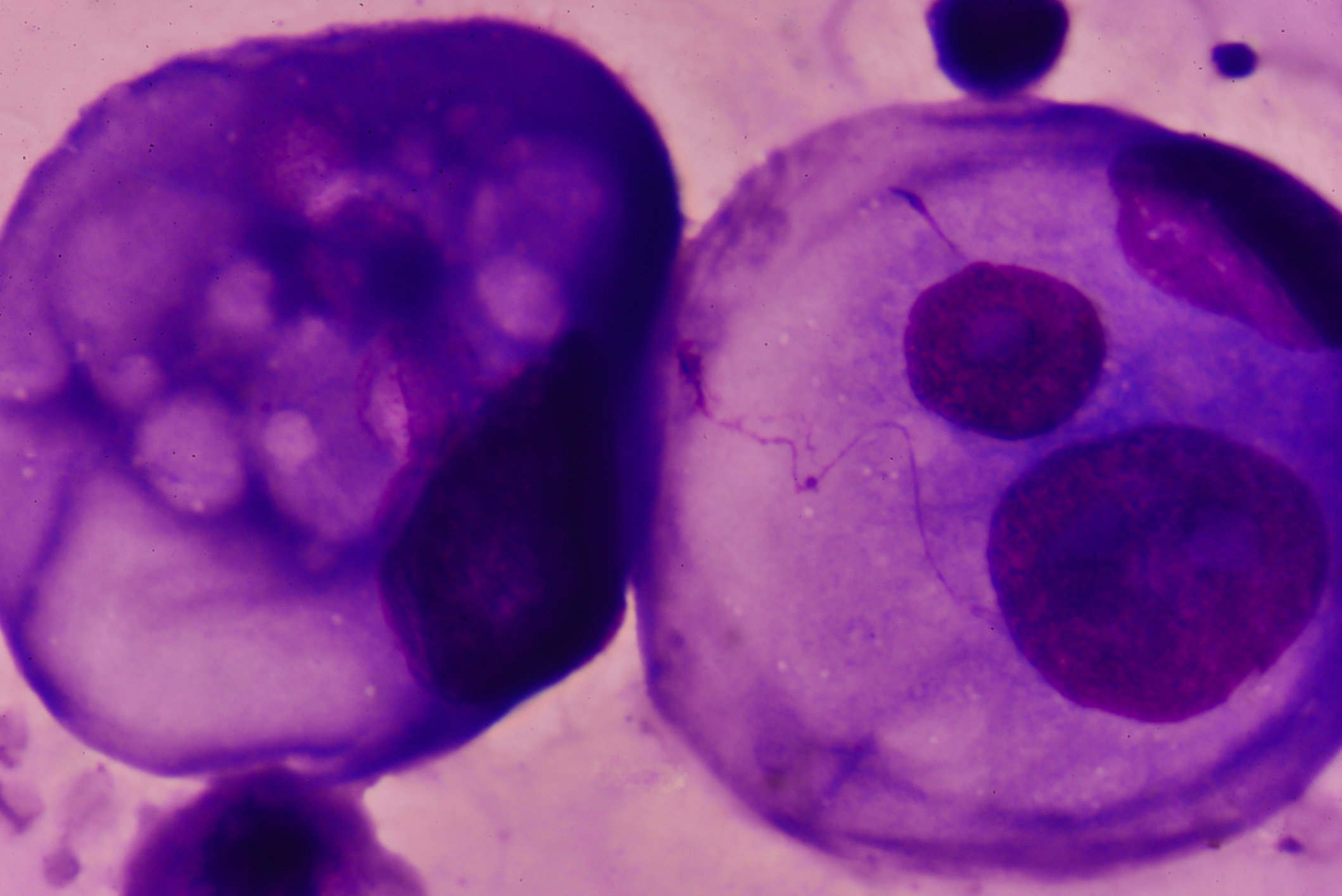

A new artificial intelligence-based blood test can identify eight common cancers by detecting the mutated DNA and proteins emitted by tumours – an approach that could reduce reliance on cancer drugs and allow disease to be treated by surgery alone.

The scientists from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, say the research lays the foundation for a single blood test for cancers of many types.

It opens the tantalising possibility of being able to detect cancers early using blood tests, although at the moment the system is limited to ovary, liver, oesophagus, pancreas, stomach, colorectal, lung and breast cancer.

The new test, CancerSEEK, measures circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) from 16 genes as well as eight protein biomarkers, then uses machine-based learning to analyse the data.

Overall, the test found around 70% of cancers, and five of the eight cancers investigated have no screening programmes for early detection.

Early detection could mean that doctors would be able to intervene sooner to remove tumours, before they spread, according to a report published online in the journal Science.

Although the system is a long way from the market, corresponding author Anne Marie Lennon told Medscape that the test could detect some cancers “early enough that they could be cured by surgery alone”.

Even those that could not be cured by surgery would probably respond better to drugs when disease was less advanced, said Lennon.

Each test is likely to cost under $500, less expensive than current screening tests such as colonoscopy and mammography.

The research is particularly exciting to the pancreatic cancer patient community as this disease is notoriously difficult to detect because symptoms often emerge once it has spread.

Ali Stunt, chief executive at Pancreatic Cancer Action, said that in eight out of ten patients the disease is only detected when it is incurable.

“We desperately need better ways to diagnose pancreatic cancer earlier to give patients the best chance of survival.”

The test will be particularly important in cases when symptoms are vague and gives a potential tool that would allow GPs to rule cancer in or out, said Stunt, who cautioned that that the 70% success rate needed to improve.

She said: “The caveat is that it now needs to be tested on people without a cancer diagnosis to see if very early disease can be detected and for it to be used as a screening tool in those at high risk of developing cancer.”

CancerSEEK is now being trialled in people who have not been diagnosed with cancer.