A history of: Scottish medical innovation

Scotland, while modest in size, has had a remarkable influence on the evolution of medical science, producing innovations that have reshaped healthcare globally. Known for housing one of the world's premier medical schools, Scotland has been home to a lineage of pioneers whose work continues to echo through modern medicine.

From the early anatomical studies of the Monro dynasty in the 18th century to the groundbreaking application of AI in drug discovery in the 21st, Scottish innovators have consistently been at the forefront of medical progress.

As we trace this journey through the centuries, discover how this legacy of innovation continues to inspire and inform current medical research in Scotland and beyond.

The 1700s:

Foundations of modern medicine

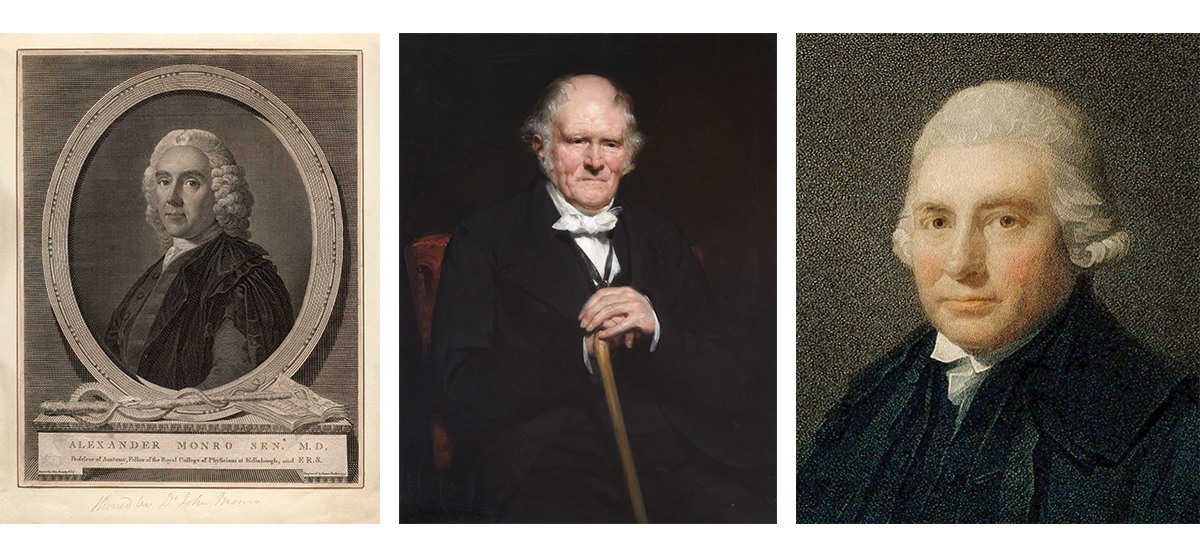

The 18th century marks the emergence of the Monro dynasty, a family whose contributions to anatomical science cemented Scotland’s reputation as a global leader in medical education. Alexander Monro, appointed the first Professor of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh, laid the cornerstone of a legacy that would last for three generations.

Images left to right:

(Left) Alexander Monro Primus by Allan Ramsay. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Middle) Alexander Monro Secundus by James Heath (1757–1834), after Henry Raeburn (1756–1823). Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Right) Alexander Monro Tertius by John Watson Gordon. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

His lectures at the old Surgeons' Hall drew large crowds, sparking widespread interest in anatomical studies, but also controversy due to the increased demand for cadavers. Despite his public condemnation of body-snatching, Monro’s position highlighted the tension between medical progress and societal norms of the time – a challenge that would be revisited two generations later during the notorious activities of William Burke and William Hare in 1828. His son, Alexander Monro secundus, and his grandson, Alexander Monro tertius, succeeded him in the Chair of Anatomy, continuing this anatomical dynasty for a staggering 126 years. Together, their work advanced the understanding of human anatomy, establishing Edinburgh as a preeminent centre for medical education.

In 1753, James Lind published his seminal work demonstrating the link between citrus fruits and the prevention of scurvy, which became one of the earliest examples of a controlled clinical trial. Although citrus was not a traditional pharmaceutical, Lind’s discovery had a profound impact on naval medicine, illustrating the therapeutic potential of dietary interventions. Not long after, William Cullen, another prominent Scottish physician, published First Lines of the Practice of Physic in 1777. This textbook systematised contemporary medical knowledge and became a standard reference across Europe and North America, further enhancing Scotland’s influence on global medical education for generations to come.

The close of the 18th century saw yet another pioneering figure emerge in John Hunter, whose posthumous work, A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation, and Gun-Shot Wounds, published in 1794, laid the groundwork for modern surgical practices. Hunter’s insights into inflammation and wound healing were foundational to the development of scientific surgery, pushing the boundaries of what was then possible in treating trauma and vascular conditions.

The 1800s:

An age of discovery and surgery

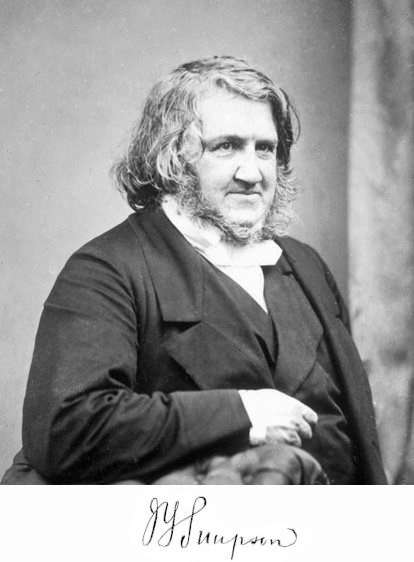

The 19th century was a period of immense innovation for medicine in Scotland, marked by breakthroughs in anaesthetics, antiseptics, and surgical techniques. In 1847, Sir James Young Simpson introduced chloroform as an aesthetic during childbirth and surgery, revolutionising the field by significantly reducing pain and suffering.

Image: Sir James Young Simpson and Chloroform (1811-1870). Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Simpson’s discovery came about through a series of informal experiments with colleagues at a dinner party, where they inhaled various substances, ultimately recognising chloroform’s potential. His announcement of chloroform as a new anaesthetic sparked immediate demand, as well as moral outrage, until ultimately gaining the seal of respectability when Dr John Snow used the agent to aid Queen Victoria in the delivery of her eighth child.

Just six years later, in 1853, Scottish physician Alexander Wood invented the hypodermic syringe, a tool that would become indispensable in modern medicine. Inspired by the mechanism of a bee’s sting, Wood’s syringe allowed for precise administration of drugs directly into the bloodstream, paving the way from smaller, measured doses. However, the risk of infection remained a prominent obstacle for doctors and it would be many years until the importance of sterilisation would be understood.

Image: Residents at the Old Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, summer 1854: left to right, John Beddoe (seated left), John Kirk (back row), Joseph Lister (seated in front row), Pringle (back row), David Christison (seated), Patrick Heron Watson (back row), Alexander Struthers (seated right). Credit: Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia Commons

In 1867, Lord Joseph Lister, another towering figure in Scottish medical history, published On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery, in which he introduced the use of carbolic acid (phenol) as an antiseptic. This breakthrough significantly reduced the incidence of post-operative infections, marking a turning point in surgical outcomes. Lister’s work, based on the germ theory of disease, set the stage for modern antiseptic and sterilisation practices, dramatically improving survival rates in surgeries.

By the end of the century, Sir Patrick Manson’s work on tropical diseases brought further acclaim to Scottish medicine. In 1896, Manson proposed the mosquito-malaria theory, which was crucial in understanding the transmission of malaria, a major global health issue at the time. His insights eventually led to the development of anti-malarial drugs, solidifying Scotland's role in advancing tropical medicine.

The 1900s:

The antibiotic revolution and beyond

The 20th century heralded the dawn of the antibiotic era, thanks to the work of Alexander Fleming. In 1928, upon returning from a holiday, Fleming noticed something unusual in one of the petri dishes he had been using to study the boil-causing bacteria Staphylococcus. He observed a strange clear substance encircling a small moldy growth that had developed in the dish.

Image: Sir Alexander Fleming,, the discoverer of Penicillin by Ethel Leontine Gabain. Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Now, for most people, the appearance of mold is rarely a cause for celebration – but for the Scottish bacteriologist mysterious secretions from one blob of mold proved to be the catalyst for a breakthrough in life-saving medication. Fleming found that his "mold juice" was capable of killing a wide range of bacteria, such as streptococcus, meningococcus, and the diphtheria bacillus. He renamed his serendipitous discovery penicillin.

While it may have been a lucky development, this breakthrough marked the beginning of modern antibiotics, transforming the treatment of bacterial infections and saving countless lives. Penicillin became the first mass-produced antibiotic and remains a cornerstone of medical treatment to this day.

Scotland’s contributions to medical innovation continued with Alick Isaacs’s discovery of interferon in 1957, a protein that plays a critical role in the body’s defence against infections. Shortly after, Sir David Jack developed salbutamol in the 1960s, an anti-asthma treatment that significantly progressed respiratory care.

Little more than a decade later, in 1978, Professor Ken Murray’s identification of the hepatitis B virus led to the creation of the first recombinant vaccine, further illustrating Scotland’s enduring impact on global health.

The 20th century closed with a series of additional breakthroughs, including Sir James Black’s development of beta-blockers, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1988. Beta-blockers transformed the treatment of cardiovascular disease, highlighting the critical role of Scottish innovation in pharmaceutical development.

As the world approached a new millennium, excitement mounted around the possibilities of a new, technology-enabled era of medicine. But the buzz surrounding this once-in-a-lifetime event could only be matched with an unexpected, and highly controversial, breakthrough – oh, and a sheep.

Image: Dolly as a lamb with her adoptive mother. Photo courtesy of the Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh

Dolly the sheep made international headlines in 1996, when a team of researchers led by Ian Wilmut at the Roslin Institute near Edinburgh announced that they had brought science fiction to life by successfully cloning Dolly the sheep. Dolly became the first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell, a process that involved transferring the nucleus from an adult sheep's mammary gland cell into an enucleated egg cell.

This milestone demonstrated that specialised adult cells could be reprogrammed to create an entire organism, challenging long-held assumptions about cellular differentiation. The achievement opened new possibilities in genetics, biotechnology, and regenerative medicine, sparking both scientific excitement and ethical debates on the future of cloning technology.

The 2000s:

Medicine in a new millennium

Entering the 21st century on a high after achieving the seemingly impossible, the pressure was on for researchers to continue Scotland’s legacy as a leader in medical innovation. But, with groundbreaking contributions spanning across stem cell research, prosthetics development, and regenerative medicine, it seems that the nation’s scientists have taken the challenge in their stride.

In a significant development for biomedical engineering, 2008 marked a milestone in prosthetics with the creation of the iLimb by Touch Bionics, the world's first commercially available multi-articulating prosthetic hand. This innovation significantly enhanced the quality of life for amputees worldwide.

In 2013, researchers from Edinburgh's Heriot-Watt University unveiled a pioneering 3D printing technique for stem cell clusters, potentially accelerating the creation of artificial organs. This innovative approach, utilising an adjustable "microvalve" to layer human embryonic stem cells, not only offers hope for future transplant-ready organs, but also provides more accurate tissue models for drug testing, reducing the need for animal trials.

The following year saw two significant breakthroughs. The University of Strathclyde developed a rapid diagnostic test for bacterial meningitis using Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS), enabling life-saving diagnoses within minutes. Concurrently, researchers at the University of Edinburgh made substantial progress in creating human liver tissue from stem cells, opening new avenues for drug testing and organ transplantation technologies.

Scottish scientists also played a crucial role in combatting the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing to vaccine development and vital research on the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In 2021, Dundee-based researchers made significant strides in understanding Parkinson's disease, identifying key mechanisms in the PINK1 gene that could lead to new treatments.

Most recently, in 2024, the University of Dundee further advanced Parkinson's research by uncovering the inner workings of a molecular switch that protects the brain against the disease's development. This breakthrough reveals unique elements of the PINK1 switch, offering new targets for therapeutic interventions.

From the anatomical studies of the Monro dynasty in the 18th century to the modern applications of AI and stem cell research, Scotland has been a beacon of medical innovation. Each century has brought new discoveries, each decade advancing the boundaries of what is possible in healthcare. Today, as Scottish researchers tackle the challenges of antibiotic resistance, cancer treatment, and neurodegenerative diseases, the nation’s legacy of medical excellence continues to inspire and shape the future of global medicine.

About the Author

Eloise McLennan is the editor for pharmaphorum’s Deep Dive magazine. She has been a journalist and editor in the healthcare field for more than five years and has worked at several leading publications in the UK.

Supercharge your pharma insights: Sign up to pharmaphorum's newsletter for daily updates, weekly roundups, and in-depth analysis across all industry sectors.

Want to go deeper?

Continue your journey with these related reads from across pharmaphorum

Click on either of the images below for more articles from this edition of Deep Dive: Commercialisation 2024