Assessing the global applicability of the UK’s ‘Netflix’-style subscription model for antibiotics

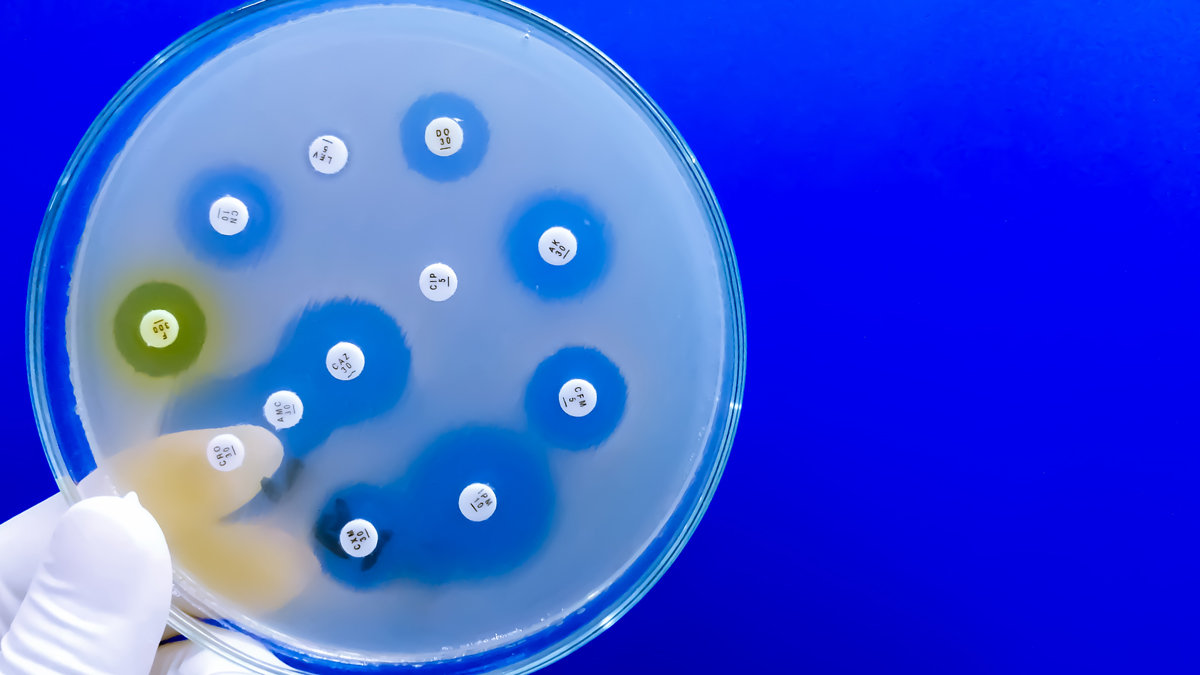

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global health crisis, estimated to have caused at least 1.27 million premature deaths globally in 2019. But, the number of new antibiotics currently in clinical development remains shockingly low: in 2020, only 41 antibiotics were being studied in clinical trials, whereas, in the same year, there were approximately 1,784 products in immuno-oncology trials.

It doesn’t appeal to the appetites of Big Pharma, either. Novartis quit the antibiotics field, selling off its infectious disease portfolio to Boston Pharma, further diminishing the number of players in this area and echoing similar exits from the likes of AstraZeneca, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly.

However, the UK’s innovative ‘Netflix style’ subscription model for antibiotics represents a groundbreaking approach to tackling AMR and fostering antibiotic innovation (and appetite). Yet, doubt remains over how likely it is to influence the pharmaceutical industry on a global scale, due to the high costs and low returns associated with traditional sales models.

Will the stable revenue stream offered through such a subscription model make it easier to attract investment within the UK and abroad?

Containing, controlling, and mitigating AMR

A new Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) study, published in The Lancet, states that AMR mortality is predicted to increase by 70% by 2050 compared to 2022. As the UKHSA states, AMR occurs when medicines used to fight infections lose their effectiveness because the organisms they target – whether bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites – have evolved or acquired adaptations to survive. The main driver of AMR is the inappropriate use of antibiotics.

In mid-September, 10 public and private funders announced a total of just over €60 million ($66 million) in funding to the non-profit Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP), ahead of the UN High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance on 26th September, during the 79th session of the UN General Assembly in New York City. Those funders included six governments (Germany, Japan, Monaco, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK), the European Union, GSK, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the South African Medical Research Council.

The purpose of the funding is to support GARDP’s strategy, which focuses on accelerating the development of much-needed antibiotics that are effective against World Health Organization (WHO) priority pathogens, and ensure people who need them get access, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where an estimated 80% of AMR deaths occur.

This need for new antibiotics, and funding for the R&D for such, comes as a result of protecting against developing AMR through sparing use of antimicrobials: manufacturers cannot be sure sales revenues will show a return on what are often multi-million dollar investments. This, in turn, affects research in the area, funds instead being invested in the surer ROI to be found in oncology, for example. This has led to no new classes of antimicrobials being licensed since the 1980s.

However, the UK has a 20-year vision for tackling AMR, rolling out over a series of five-year National Action Plans (NAPs), aiming to bring together organisations across government to address the issue, with detailed tangible outcomes by 2040. The first five-year national action plan for antimicrobial resistance, ‘Tackling antimicrobial resistance 2019 to 2024’, reduced the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals, as well as developing improved surveillance systems. It also piloted a new payment scheme for antibiotics on the NHS: a Netflix-style subscription model, de-linking reimbursement from volume of sales, a so-called “pull incentive”, with payments based on the added value to the whole-health and social-care system, not just to individual patients. The model falls under Commitment 6.2:

“We will implement purchasing arrangements for new antimicrobials that de-link the price paid for antimicrobials from the volumes sold, monitor and evaluate impact, and advocate for the wider use of these ‘subscription models’ in other countries.”

As NICE notes, investing in new antimicrobials is not “commercially attractive” because of the necessarily strict controls and restrictions of use for the purpose of avoiding AMR exacerbation. As already stated, it’s an ROI consideration. Thus, the UK Government’s 2019 national action plan for AMR was meant to test how to incentivise companies to invest in new antimicrobials – utilising a rather different model from that used for other medicines. Together with NHS England, NICE ran a pilot project testing an innovative approach that pays companies a fixed annual fee for antimicrobials. Sums were based primarily on a health technology assessment of their value to the NHS, instead of volumes used.

Value versus volume, quality as opposed to quantity

According to the Antimicrobial Resistance Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, it is “imperative to understand the economic market factors which drive the inefficiencies in addressing [AMR], as well as the policy options that are being considered.” Indeed, there is considerable perceived financial risk for industry, given the historic model of “volume-based sales necessary to re-coup sunk R&D costs.”

Essentially, the Netflix subscription model involves a lump-sum payment that is paid to a pharma company in return for limitless product access (think about how many TV programmes or films you have enjoyed watching under a monthly direct debit set-up for your actual Netflix streaming service). Antibiotics are not the only disease area in which it has been trialled: there was the Hepatitis-C drug Sofosbuvir in Australia in 2016, for instance. Nonetheless, the UK NHS is the first healthcare system to adopt a subscription payment model for new antibiotics on a permanent basis.

The Department of Health, NHS England, and NICE completed an evaluation of two new antibiotics – Pfizer's Zavicefta (ceftazidime/avibactam) and Shionogi's Fetcroja (cefiderocol) – that will be paid for using the new subscription-like model, with NHS England paying a fixed annual fee for access to the two medicines of £10 million per year, calculated based on the value they offer the health service, regardless of how much is used to treat patients. NHS England announced details of the new commissioning route for antimicrobials in May 2024, and launched the first round of procurement last month, in August of this year.

After making an application to the scheme, drugs are assessed for eligibility based on factors such as the pathogen they target, the hierarchy of pathogens being determined by the WHO’s priority list. If successful, according to the proposed model, the drugs’ value will be assessed across seventeen criteria, including surety of supply, antimicrobial stewardship, and manufacturing practices. A company can then be offered one of four payment band ranges – £5m, £10m, £15m, or £20m. A “fair share payment”, it is meant to reflect England’s portion of the global market, which is around 2%-3%. The devolved nations – Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland – can participate in the scheme without having to duplicate work, also.

The contract terms have not yet been fully finalised – and industry wants reassurances for “exceptional circumstances” (such as what happens in the event of another pandemic) – but the next consideration is the global applicability of such a subscription model.

The potential for subscription models abroad

Grace Hampson, an associate director of the independent health economics research organisation, the Office of Health Economics (OHE), has said that the subscription model has “the potential to be revolutionary.” But is that so globally?

Certainly, eyes will be on England from other nations, and other similar models are duly in the pipeline abroad. What is paramount, though, is that global endeavours are undertaken: no man is an island, and no one country can ameliorate the worldwide AMR situation alone. Indeed, if G20 countries rolled out payments based on their percentage share of the global market – remember, England is a mere 2%-3% of that share – this would act as a significant global “pull incentive”, even without LMICs making a contribution.

As the ABPI’s value & access policy director, Paul Catchpole, notes: “All countries globally, particularly the G7 and G20 nations, need to make their own contributions, collectively, to add up to significant amounts of money that will make antibiotic research more commercially attractive to stimulate development.”

To this end, across the pond, the US proposed the PASTEUR (Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions To End Upsurging Resistance) Act in 2021, similarly operating as a subscription-type model. However, it has not been passed, despite the 2023 bill lowering the suggested funding from $11 billion to $6 billion. Back on the Continent, the EU is contemplating a transferable exclusivity voucher (TEV), based on a reward system, whereby developing a critically needed drug (e.g., an antibiotic) in turn extends the patent a pharmaceutical company has on another drug. Recent analysis by the Center for Global Development found that the new EU antimicrobial incentive programme could save some 20,000 lives and deliver $15.5 billion in total benefits, with – importantly – an ROI of 4:1 over the next decade.

European countries adopting such an approach to fit their national systems include Sweden, which has implemented a revenue guarantee for five antimicrobials active against Priority 1 pathogens on the WHO priority pathogen list, while Germany and France have both developed an adjusted reimbursement system for antibacterials, allowing larger payment to companies.

While it remains to be seen as to how effective the uptake of this “pull incentive” Netflix-style subscription model across the international map will be, what remains certain is that the antibacterial market is broken, that the antibiotic pipeline needs a cash incentive for an R&D interest boost, and that AMR is not going anywhere anytime soon. While countries broadly support the concept, the question that also lingers is which new antimicrobials will be most suitable for a “subscription” or “pull incentive” approach.

Rex and Outterson might have stated that antibacterials should be thought of as the “fire extinguishers” of medicine, but – in a world where we yet battle infectious diseases such as COVID and mpox in multiple variants – what type of fire, and at what cost, will it take to drive nations down a suitable, if not fully perfect, payment model path and arrest AMR before it becomes truly unstoppable?

About the author

Nicole Raleigh is pharmaphorum’s web editor. Transitioning to the healthcare sector in the last few years, she is an experienced media and communications professional who has worked in print and digital for over 18 years.

Supercharge your pharma insights: Sign up to pharmaphorum's newsletter for daily updates, weekly roundups, and in-depth analysis across all industry sectors.

Want to go deeper?

Continue your journey with these related reads from across pharmaphorum

Click on either of the images below for more articles from this edition of Deep Dive: Commercialisation 2024