Pharma warns of European exit – but British public needs more convincing

If there is one thing that big pharma companies hate more than anything, it's uncertainty about the future of their markets and regulations. But that's something the industry's leaders in Europe will have to endure in 2016 as the UK ponders an exit from the European Union (EU).

It looks likely that the UK will hold its referendum on whether to stay in the EU or leave it by June this year, which means big multinational businesses like pharma face a frantic few months, considering the options and possible scenarios.

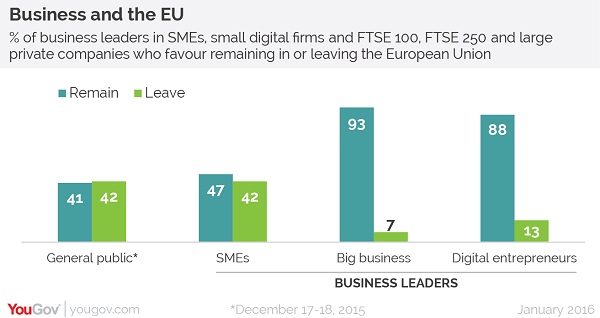

The polls show that big corporations which work in the UK are almost all against a so-called 'Brexit' from the EU, including pharma.

But that picture contrasts with small businesses, and the British general public, where opinion is fairly evenly split between those for and against continued EU membership.

The referendum has its roots in the UK's ruling Conservative party, which has been riven by divisions over Europe for decades.

Eurosceptics in the party want to see Britain take back many powers from Brussels, but Prime Minister David Cameron has come out in favour of staying within the union. However he has pledged to secure major concessions and reforms to the EU which he says will benefit the UK.

In particular, concerns about uncontrolled immigration have risen up the political agenda in the last few years, and supporters of the 'Leave' campaign say it is the UK's chance to seize back control of its borders. Mr Cameron is expected to announce today that he has secured a deal with EU leaders to allow the UK to withhold benefit payments to new EU migrants to the country – with the aim of deterring some incomers. The Prime Minister hopes these and other concessions will be hailed as a success by voters, who would then carry a vote to 'Remain'.

Of course, the free movement of people within the EU is generally seen as a major advantage by big businesses such as pharma. This is especially the case of Britain's home-grown pharma giants AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), who want to attract international scientific talent to their R&D operations in the UK.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, GSK's chief Sir Andrew Witty made clear his support for the European project.

In particular, he said the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the EU's centralised drug regulator, based in London, had helped the continent compete with the US.

"Europe has gone from 27 fragmented, independent, not-talking-to-each-other regulatory authorities in the healthcare space to one," Witty told The Financial Times (FT) "That's a big deal."

The newspaper spoke to other high-profile pharma bosses who echoed this pro-European sentiment. John Lechleiter, chief executive of Eli Lilly, told the FT it would be a "shame and a mistake" if the British decided to leave.

The US company employs 2,800 people in the UK across four sites, including a large drug discovery centre in Surrey specialising in neuroscience, including Alzheimer's disease.

Mr Lechleiter said the firm's UK research centre was "literally a global research centre" and that he thought they had people there from every country in the EU. "We tend to think about our UK operation ... as being very much a European centre."

While personally believing Brexit would only diminish and isolate the UK, Leichleiter stressed that these were only his personal views. In terms of direct effects on the UK market, he believed these would be relatively insignificant.

Pharma wants harmonisation

There is no doubt that the pharma industry wants to see greater harmonisation within Europe, and has long bemoaned its fragmentation, particularly the huge variation in the pricing and reimbursement arrangements across the continent.

A British exit from the EU would only complicate matters, with questions raised about whether it could remain within the current centralised drug approval system run by the EMA.

This is possible: Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein are all non-EU members, but participate in the EMA as part of the European Economic Area (EEA).

By contrast, Switzerland is also a non-EU member, and not part of the EEA, and therefore has its own separate drug approval process.

Supporters of Brexit point to Switzerland as an example of a country which has enjoyed huge success in fostering its pharma industry despite not being in the EU.

Certainly, the Conservatives have introduced a number of policies aimed at making the UK a more attractive destination for life sciences, such as lowering the corporate tax rate and introducing other tax breaks such as the 'patent box' system.

Life Sciences minister George Freeman has also helped oversee the introduction of UK-only regulatory initiatives such as the Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS), and the forthcoming Accelerated Access Review. These look designed to make the country more competitive in comparison with the US – eschewing the EU-wide reform which would undoubtedly have a bigger impact, but far harder to achieve consensus on.

The UK retains autonomy over this legislation and healthcare spending, regardless of whether it remains in Europe. Nevertheless, pharma doesn't like surprises, and Brexit would be bound to entail extensive negotiations about future regulatory arrangements, as well as some unintended consequences for it and for Europe as a whole.

So while pharma is sure that the UK must 'stay', many of its citizens must now be reassured and convinced this is the best course of action.

About the Author:

Andrew McConaghie is pharmaphorum's managing editor, feature media.

Contact Andrew at andrew@pharmaphorum.com and follow him on Twitter.