Pharma’s crippling addiction and how to cure it

The 'find it, file it, flog it' approach to drug development has to be abandoned for a truly patient-centred approach, says Hedley Rees.

Hedley Rees

What is the addiction?

Ever since Glaxo won the battle of the marketing muscle with its ulcer drug Zantac in the early 1980s, pharma has been struck with a crippling addiction – namely, gambling on serendipitous discoveries in the hope of making blockbuster returns.

For those unfamiliar with the battle, Tagamet, developed by Smith, Kline and French, was the first to market, but was overtaken by Zantac, soon after its launch in 1981, with what was reported to be a superior marketing effort.

So began the era of the blockbuster, and with it the notion that patented compounds, with a licence to sell, could make mega returns. This resulted in what I have resorted to calling the 'find it, file it, flog it' approach to drug development. It involves discovering a compound and patenting it (find it), placing it into a development pipeline intended for regulatory approval to market (file it), and then marketing the approved product with the utmost verve and vigour (flog it).

This became the reigning paradigm for drug development and exists to this day.

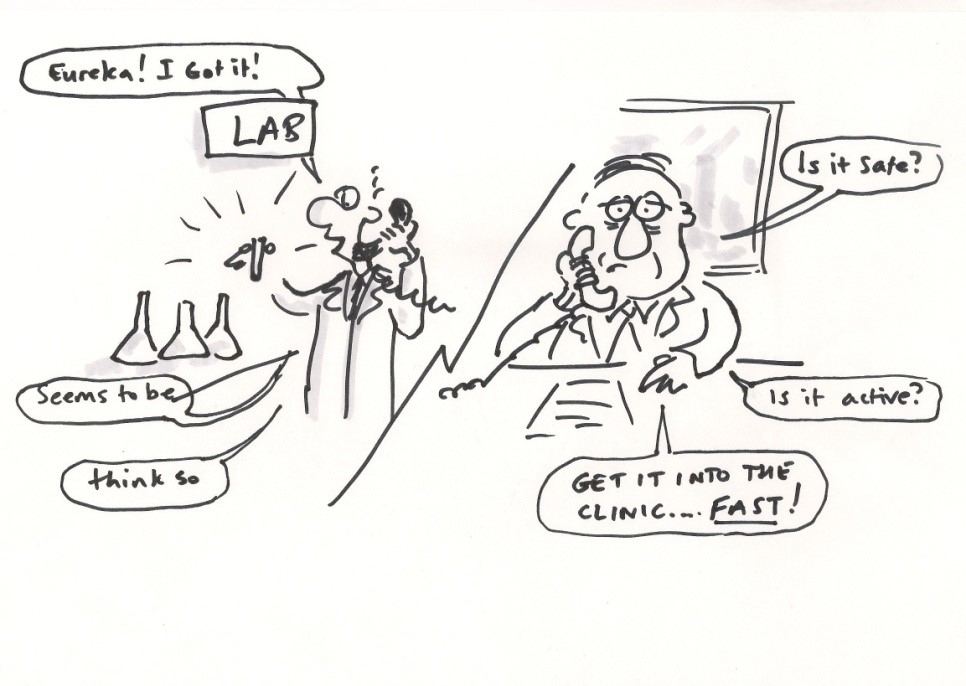

Figure 1. The reigning paradigm of drug development

In Figure 1 (courtesy of Dr Graham Cox, expert witness) the eager scientist phones his boss, who is under pressure from above to move compounds into development. The race is now on to get the magic powder into trials by making larger quantities to test on animals. Figure 2 shows the scientist's 'baby' hastily passed along the development conveyor belt as the patent clock ticks away.

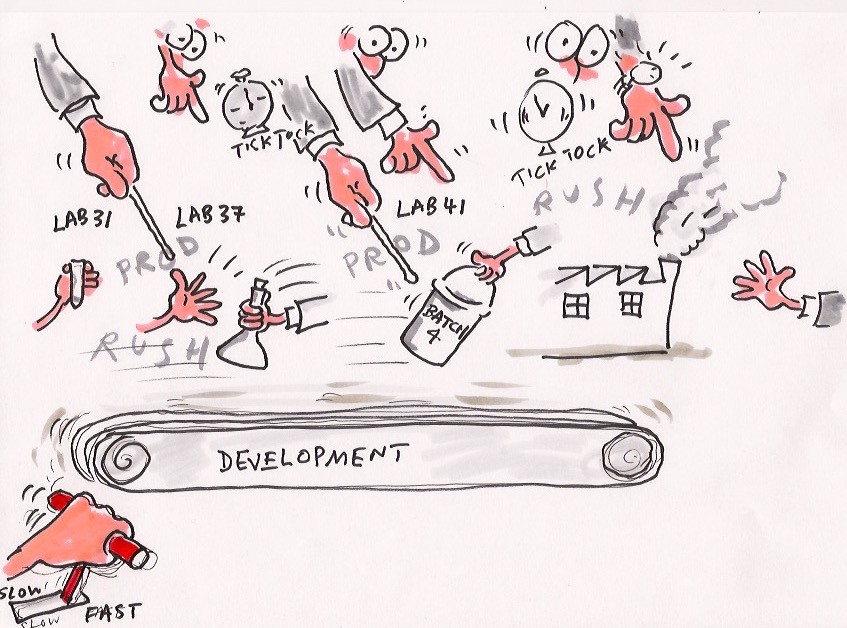

Figure 2. The patent clock is ticking

The race is on to gain that vital regulatory approval; and guess what? Only one in 250 of those starting the race get over the line (US Government Accountability Office figures). The rest fall by the wayside during the journey, a phenomenon now dubbed the 'valley of death', which gave birth to the patent cliff.

Crippling effect

The current Triple F approach to drug development, as outlined above, and the lifestyle it has spawned, has encouraged big pharma to engage in two crippling activities: outsourcing of critical assets and abandoning of out-of-patent products – in a misguided attempt to satisfy investor demands to maintain blockbuster earnings.

This has had the opposite effect. By outsourcing these assets, big pharma has divested its ability to develop new products. Prof Andrew Cox, expert in procurement and outsourcing best practice, is quoted in my book1 saying: "Unfortunately for the major pharmaceutical companies that used to be the 'channel captains', who controlled the industry and all of its major supply chains through a judicious control internally of critical assets, there has been considerable evidence of very poor practice in outsourcing in recent years."

Consider the example of aircraft manufacturer Boeing, which dabbled with increased levels of outsourced development for the Dreamliner and suffered a reported 18-month delay, as well as much pain and suffering. Author Peter Cohan said: "But by outsourcing both the design and the manufacturing, Boeing lost control of the development process."2

As for dropping out-of-patent products, the impact has been equally crippling, not just for big pharma, but for the industry as a whole. Roughly 80% of drugs are in the hands of generic companies and earning tidy profits. Those are profits big pharma could have enjoyed, especially since they had the benefit of scale when under patent protection. As it is, the large R&D-based pharma companies have to chase niche and orphan indications, and charge eye-watering prices too.

The implication for the industry as a whole is even greater, as recent events are proving. Opportunistic businessmen, such as Martin Shkreli, CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals and J Michael Pearson, former CEO at Valeant Pharmaceuticals, have been snapping up out-of-patent products ignored by big pharma and ramping up the prices to extraordinary levels.

So what is the cure?

The cure lies in beating the addiction, starting by accepting that big pharma needs a fundamental change. It cannot continue launching molecules into development with little understanding of whether they will work or not.

Things need to change radically, by turning product development on its head, as other sectors did in the 1950s and 1960s. Companies such as Toyota, Honda, Nissan and Matsushita led the charge to place end-user value at the forefront. The results were startling as we all know now.

The same has to happen in big pharma, the alpha male of the industry. Healthcare professionals (HCPs), and the patients they serve, have to become the central focus of development activities. They must be deeply involved and consulted on the indication at the earliest stage, even before pre-clinical assessment takes place. It is not sufficient to involve only a small number of investigators, appointed by the pharma company, in trialling drugs; attrition rates in the industry prove that.

Once this engagment takes place and the value proposition is established, prototypes must be built and pressure-tested before progressing into commercial development. Maximum use of predictive technologies must be employed, using in silico and ex vivo techniques. These methods have moved on unrecognisably in recent years, but the industry is reluctant to apply them in any meaningful way.

To achieve this, discovery research scientists need to stay and help develop the prototypes, rather than move on to 'discover' new compounds, oblivious to any issues arising from their previously orphaned offspring. Only those prototypes passing muster under the scrutiny of a multi-disciplinary review team (including the HCPs) would move forward into development for end-user markets.

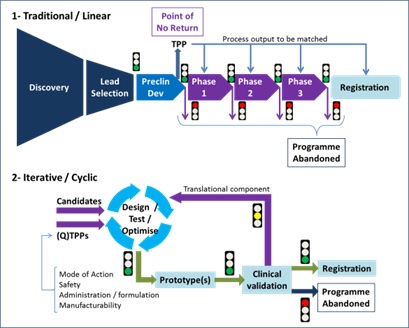

Figure 3 shows a schematic comparing the current and proposed new approaches. Note the iterative nature of the proposed approach, whereby candidate compounds are designed, tested and optimised and then subjected to clinical validation using predictive technologies. The power of this approach is the depth of scrutiny each compound receives, weeding out potential failures at the start.

Figure 3: Alternate stages in the drug development process, courtesy of expert witness Dr Jesús Zurdo, Lonza Biologics

Once on the road to development for commercial markets, a 'production system' approach must be taken, whereby the target destination is a product in end users' hands, not the statistical endpoint of a clinical trial, as it is today.

This means that a much broader range of skills, including those from engineering, must be recruited and applied; also leadership in taking the product to market will be a single continuum, rather than a two-tier approach as at present.

This severely challenges the industry's historic tendency to withhold allocation of resources until the later stages of clinical trials. However, this has only come about because attrition rates are so high. The solution is to reduce the attrition, as we suggest here, rather than withdraw the resources.

A final message for pharma CEOs

The only stakeholders who can make change happen are the CEOs of big pharma companies. Their predecessors discovered a wonderful way to build businesses, as summed up by Merck founder George W Merck: "We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear. The better we have remembered it, the larger they have been!"

I rest my case.

References

1 Rees, Hedley. Find It, File It Flog It: Pharma's Crippling Addiction and How to Cure It, 3 December 2015.

2 Cohan, Peter S. You Can't Order Change: Lessons from Jim McNerney's Turnaround at Boeing, Portfolio Hardcover, 2008.

About the author:

Hedley Rees is a pharmaceutical supply chain management consultant and the author of 'Supply Chain Management in the Drug Industry: Delivering Patient Value for Pharmaceuticals and Biologics', plus the recently published book 'Find It, File It Flog It: Pharma's Crippling Addiction and How to Cure It'.

He holds a degree in production engineering from the University of Wales and an executive MBA from Cranfield University School of Management.

After working as an industrial engineer, Rees held senior positions at Bayer UK, British Biotech, Vernalis, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics and OSI Pharmaceuticals before becoming managing consultant at UK consultancy PharmaFlow, specialising in operations and supply chain management in the life science sector.

He was co-chair of the annual FDA/Xavier University-sponsored PharmaLink Conference in Cincinnati from 2011 to 2014. He speaks at international conferences and hosts podcasts and webinars.

Read more from Hedley Rees:

Patient-centric pharma: brave new world or same old empty promises?