Tunnah’s musings: Rare diseases hold key to future of drug development

After chairing a panel discussion at this year’s Cambridge Rare Disease Summit in late October, Paul Tunnah muses on the lessons that can be learned for the future of drug development from the collaboration and innovation in this space.

In late 2015 I had the pleasure of attending the inaugural Cambridge Rare Disease Summit in the UK, a new event effectively marking the launch of the Cambridge Rare Disease Network (CRDN), which brings together all those local groups that have an interest in this area of medicine.

This year, I was flattered not only to be invited to attend again, but also to moderate a panel discussion as part of the proceedings, with free rein to position this as appropriate. It was clear to me that a good focus for this session would be a discussion on the parallels between rare disease research and the much broader evolution of personalised medicine.

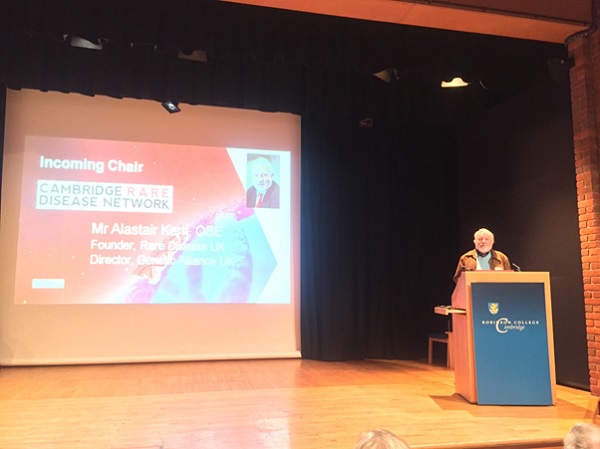

The definition of a rare disease, in Europe, is one that affects less than five in every 10,000 people but, collectively, the prevalence of rare diseases is much higher, at around 5-10% of the population, depending on the country. In the UK, for example, around 3.5 million people have some form of rare disease, which, as the incoming chairman of CRDN, Alastair Kent OBE, pointed out, is greater than the population of Wales!

To put this figure in perspective, it is estimated that there are fewer people – around 2.5 million – living with some form of cancer in the UK, collectively spanning the major tumour types (for example, breast, colorectal, lung and prostate) right down to cancers that are themselves defined as rare diseases. But, if you look within the major tumour types, you will find that, while the site of presentation is consistent, the genetic basis is extremely varied. In effect, these common diseases are, at the genetic level, collections of many rare diseases. Over time, we are learning that the same is true for many other areas, such as heart disease, diabetes and respiratory disorders.

This understanding has driven the rise of personalised medicine, targeting the genetic underpinnings of a disease, rather than its morphological presentation. While it is important to recognise that not all rare diseases are ‘genetic’, in the sense of being present from birth, it does drive interesting parallels between the two fields. So this was the focus for my panel, entitled ‘Riding the personalised medicine wave to accelerate progress in rare disease treatment’.

Alastair Kent OBE, incoming chair of the Cambridge Rare Disease Network, addressing the Summit.

The four panellists collectively represented the nature of collaboration that you can see everywhere in rare disease research.

Dr David Pardoe, Head of Growth Projects at MRC Technology, talked about the work the charity is doing in funding novel research and, specifically, in joining the dots between academia, biotechnology, pharma companies and other charities. This is not just about connecting great science with commercial capabilities, but also about exploring new funding models, e.g. crowdfunding and societal impact investment to accelerate development of new treatments.

Dr Birgitte Volck, Head of Rare Disease R&D for GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), reiterated the importance of collaboration and the important role that ‘big pharma’ plays in helping both smaller biotechs and academic researchers progress critical research to a stage where it can be of benefit to patients. Volck is in a prime position to understand this research ecosystem, having only recently joined GSK, after four years with Swedish Orphan Biovitrum (SOBI) and working for the ‘original biotech’, Amgen, prior to that.

Dr Richard Scott, Clinical Lead for Rare Disease at Genomics England, provided an update on the 100,000 Genomes Project and how important it is with regard to rare disease research. The huge investment in this project, which itself collaborates with multiple academic and commercial partners, will surely help to drive quicker diagnosis of known disorders and even identification of new rare diseases over time. Critically, the evidence base they are building is freely accessible for non-commercial research organisations (and within the bounds of data privacy).

Finally, it was a distinct pleasure to feature Emily Kramer-Golinkoff, the Founder of the US not-for-profit organisation Emily’s Entourage, on the panel. The only participant not to have the title ‘Dr’, Emily is more qualified than most medics on the challenges of living with a rare disease, having lived all her life with cystic fibrosis (CF). The work she has done with Emily’s Entourage, in raising millions of dollars of research funding, accelerating trials and building a groundswell of support and publicity, is inspirational and has even garnered the attention of the White House, as the US seeks to lead the world on ‘Precision Medicine’.

But one important point that Kramer-Golinkoff makes about more prevalent rare diseases like CF is that they are also, like many common disorders, collections of many different genetic subtypes. Novel therapies like ivacaftor are delivering real step-change for some CF patients by addressing the underlying cause of the disease, but only for the small proportion with the relevant genetic mutation. As with other genetically complex and diverse diseases, like breast cancer, it is important to keep pushing for novel therapies that will help all patients, not just the minority.

The perspectives represented by the above panellists in our discussion were reflected in all the presentations throughout the day, from scientists, charity leaders, medical professionals, patients and their families. These conversations and collaborations are also happening every day of the year for those working in the rare disease space.

For the sake of current and future patients, whether relating to a ‘rare disease’ or rare subtype of a more common disorder, it is important to listen to them, learn and adapt the way we do medical research. This type of collaboration and innovation is the future.

If you get chance to come along to next year’s Cambridge Rare Disease Summit I would recommend it and, in the meantime, stay well.

Visit the Cambridge Rare Disease Network for more information about its work and the Summit.

About the author:

Paul Tunnah is CEO & Founder of pharmaphorum media, which drives better communication, connection and collaboration between the pharmaceutical industry and other healthcare stakeholders. Its suite of services, from publishing (www.pharmaphorum.com) to its healthcare engagement agency (www.pharmaphorumconnect.com), is underpinned by the common strengths of extensive global networks, a firm finger on the pulse of changing market dynamics and deep expertise in creating engaging, relevant media.

For queries he can be reached through the site contact form or on Twitter @pharmaphorum.

Have your say: What lessons does rare disease research hold for the future of drug development?