Translation from research to clinical significance - a due-diligence analysis

Translational research partnerships help turn academic excellence into new treatments for patients – but they require due diligence at every step along the way.

The general public perceives research to be a platform by which novel discoveries, that will ultimately benefit humanity, are made available. These discoveries may be novel drugs or technologies to treat a wide range of diseases that affect mankind. However, unlike these expectations, research conducted in universities is typically directed towards the basic sciences, and often has little or no commercial value.1

Academic scientists tend to strive for excellence in research through publications and presentations in scientific meetings. Universities are now altering this focus by not only developing basic science programmes, but also developing applied research programmes that are socially beneficial.1 This change has been supported by governments in the US and Europe, which support translational research. Translational research is commonly understood to be a discipline that integrates diverse scientific disciplines to improve public health.1-3

"Unlike basic research, translational research is characterised by its potential commercial value"

Unlike basic research that has no independent commercial value, translational research is characterised by its potential commercial value, which can itself replenish funding for basic research and hence functions as a feedback loop that supports basic research programmes and innovation - the driving forces of translational research. 1-3

Academic technology transfer

The concept of academic technology transfer was formally introduced in a 1945 report entitled 'Science - the endless frontier'.5 This report was instrumental in stimulating the US federal government to substantially increase funding for research, and led to the formation of organisations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR). These organisations fund the majority of research in the US.5

While the US government's efforts to fund basic research increased over the years, there was little done to stimulate the commercialisation of basic research.5,6 As a result, academic research was gradually sinking into industrial irrelevance.

In 1980, legislators and administrators came together to permit universities and businesses, who conduct research using federal funds, to elect ownership of their inventions and develop and proceed with the commercialisation of the finished products. This landmark policy was introduced through a piece of legislation known as the Bayh-Dole act, sponsored by senators Birch Bayh and Robert Dole.5-7

"The creation of Translational Research Centers (TRC) has helped universities to routinely participate in out-licensing agreements."

This legislation helped stimulate the creation of separate patenting and licensing divisions commonly known as 'Technology Transfer Office' (TTO) within a college or university that would support the patenting and licensing of inventions.6 Many universities and colleges also formed Translational Research Centers (TRC) to cater to the need of researchers involved in translational research. As a result, universities now routinely participate in out-licensing agreements.5,6

TRCs and TTOs

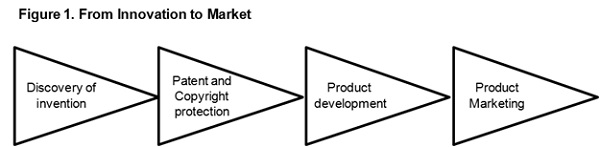

Subject to relevant laws, like Bayh Dole, and relevant contacts, a university typically owns inventions made using university resources. As the owner with a vested interest in the commercial success of products, the university is often the sole determiner of whether it intends to license and/or independently commercialise such inventions. As the university's representatives, the TRC and TTO together (collectively referred to as 'Technology Offices' [TOs]) serve as an important bridge, connecting inventors with internal and external resources to help guide an invention through the various internal and external hurdles (Figure 1) that must be overcome before successful commercialisation.

Internally, the TOs serve a variety of functions, including liaison with the inventors, educating them about the invention process, including the protection of the invention via intellectual property rights, and identifying appropriate sources of funding for the further development of the product.

Differentiation

While both the TRC and TTO are critical to commercialisation of the invention, each plays a different role in the process. The TRC, an inward-facing division, plays a major role in providing inventors with the required infrastructure for the development of their product.

Unlike the TRC, the TTO is primarily responsible for evaluating the importance and the commercial value of the inventions and is hence entrusted to obtain, protect and manage the university's intellectual property, including that derived from research. The TTO is also responsible for the licensing and transfer of inventions to third party organisations for product development and commercialisation.

University-managed profit sharing

If an invention is eventually commercialised or appropriately out-licensed, there will typically be some type of profit sharing with the inventors to give them an incentive. Each university has its own rules that govern profit sharing resulting from an invention. Generally, the profits are distributed among all the personnel listed as inventors or contributors to the inventions; however, the distribution of profits is based on the level of participation of each person involved in the development of invention. Traditionally, the lead investigator takes the most profit (up to 30 per cent)4 and receives additional support for laboratory research. The rest is divided among the other personnel, plus the various university departments, including the TTO and the TRC.

Out-licensing and sale

Inventors with strong entrepreneurial ambitions may out-license an invention from the university to further develop it. In such situations, the university outsources the risk of non-commercialisation while the inventor benefits from an increased share of profits by only paying a licensing fee to the university. Nevertheless, since the university has a vested interest in the company's success, it may also assist in finding a commercial partner.

Components of translational research

There are two major stages to the translational research: the first is focused on the conversion of basic research concepts into concepts of clinical significance; the second transfers clinical findings into clinical trials that move the basic research from laboratory to improving public health.8,9

Stage 1: Conversion into concepts of clinical significance

While conducting translational research and looking into the transfer of a technology to a company, or entering into a collaborative agreement with a company, due diligence should be undertaken on a number of issues that are critical in preserving the interest of everyone associated with the invention.10 An investigator must begin with an honest evaluation of the commercial viability of the idea. Those with limited understanding of the commercialisation process can either discard their findings or get overly excited about their discovery. University TTOs can help temper expectations by identifying and explaining the appropriate commercial value of the discovery, and predicting the feasibility of moving from 'bench-side' to 'commercialisation.

Internal due diligence

Before inappropriately spending additional resources, the inventor must evaluate the novelty of the invention by comparing it with commercially available products and those in development and assess its commercial viability. Considering the resources required to do this, the investigator may ask for a pre-assessment of the invention with the TOs. The TOs can not only advise but also provide and recommend resources for the commercialisation, market potential and returns for the invention.

IP protection

Based on the commercial viability of the product, derived in conjunction with the inventor/s and attorneys, the TTO evaluates whether to spend the resources to protect the intellectual property surrounding an invention. This commercial viability assessment is made after considering a number of issues including:

* The superiority of the invention compared to existing products;

* The market potential of the invention;

* The potential profit margins associated with the commercialisation of the product;

* The desire of third parties to in-license the invention

* The patent worthiness of the invention.

After the appropriate evaluation, the TTO may proceed with protecting the invention using a combination of patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets and other forms of Intellectual Property (IP) protection. In order to delay costs to evaluate commercial viability, a provisional patent may be filed to provide a period of up to 12 months during which final improvements to the invention can be made by the inventor to further solidify his decision on whether to convert his provisional patent into a non-provisional patent.

Funding for research and preclinical trials

Once IP protections have been filed or addressed, appropriate FDA regulatory steps may need to be addressed. This may include the submission of an IND (Investigational New Drug) Application with the FDA.8,9 To initiate the filing of an IND, pre-IND research must be conducted and data must be collected. The TOs can be critical in evaluating the appropriate data to collect. The pre-IND data that will be collected may be the result of collaborative efforts between several investigators and organisations. Accordingly, in the interest of self-protection, the TRC must ensure that confidentiality and non-compete agreements are in place.11,12 The university TRC can play a major role in executing such collaborative efforts and evaluating the resources that will be required for this endeavour. Once data has been collected, an IND may be filed by the TOs or an appropriate third party.

Funding sources

Inventors often find that great inventions often perish in the fire of insufficient funding. To avoid this, the inventor and TRC should identify appropriate funding sources.

Federal agencies, such as the NIH, provide funding in the form of grants, awards and loans for investigators to support certain fledgling inventions. The K30 and Clinical and Translational Science Award programmes are examples of funding that supports the training of scientists in translational research. Additional resources may also include grants like SBIR (small business innovation research) and STTR (small business technology transfer).13

There are also numerous local and national charities and foundations that sponsor specific disease-related studies. To appropriately target a charity an investigator must identify not only the disease target of his invention, but also identify the appropriate association or foundation that may fund such research efforts. For example, if the target disease affects kidneys the appropriate funding source may be the American Society of Nephrology or the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (commonly known as NEPTUNE). For inventions that target heart disease, the American Heart Association is a potential donor.

Conclusion

It is evident that the translation of basic research to commercialisation requires collaborative efforts from various governmental, semi-governmental, non-profit and commercial organisations. A boom in the past few decades in translational research has brought us closer to finding cures for many deadly diseases. Although the primary mission of an invention is to benefit society, it is also critical that everyone associated with the development of an innovation is also appropriately rewarded (intellectually and monetarily). This may be achieved through preserving IP rights and working closely with the various internal and external stakeholders to commercialise and bring success with the invention.

References

1. Levy H M. The transformation of basic research into commercial value: economics aspects and practical issues. J Entrepreneurship Management and Innovation. 2011; 7:4-15.

2. Geoghegan-Quinn M. European Commissioner for Research, Innovation and Science "Horizon 2020 – A Paradigm Shift for Funding Research and Innovation in Europe". European press release, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-14-65_en.htm. Accessed 25 March 2014.

3. Plos Blog. Translational Research vs. Basic Science: Comparing Apples to Upside-down Apples. Website http://blogs.plos.org/thestudentblog/2013/11/19/translational-research-vs-basic-science-comparing-apples-to-upside-down-apples. Accessed 25 March 2014.

4. University of Pennsylvania. Website http://provost.upenn.edu/policies/faculty-handbook/research-policies/iii-e. Accessed 25 March 2014.

5. University of California Technology Transfer. The Bayh-Dole Act, A Guide To The Law And Implementing Regulations. See http://www.ucop.edu/ott/faculty/bayh.html#FN10.

6. Markel H. Patents, Profits, and the American People — The Bayh–Dole Act of 1980. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369(9): 794-796.

7. US Government Accounting Office (GAO) Report to Congressional Committees entitled "Technology Transfer, Administration of the Bayh-Dole Act by Research Universities" dated 7 May 1998.

8. National Institute of Health. A '20-20' view of invention reporting to the National Institutes of Health. NIH GUIDE. 1995; 24(33).

9. Cleare J M. We're talking tech transfer. Where did it come from and where is it going? Biointernational Convention. 2008. 34-35.

10. Inside Indiana Business. IU School of Medicine Forms Two New Companies. See the website http://www.insideindianabusiness.com/newsitem.asp?ID=21814.

11. Shah K A et al. The Ethics of Intellectual Property Rights in an Era of Globalization. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2013. 841-851.

12. Rubio D M et al. Defining translational research: implications for training. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):470-5.

13. National Institutes of Health. Grants and Funding. See the website http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/sbir.htm. Accessed 21 March 2014.

About the authors:

Darshan Kulkarni is the Principal Attorney at the Kulkarni Law Firm. With his background as a PharmD, his Juris Doctorate and a Masters in Quality Assurance/ Regulatory Affairs, he provides legal, regulatory and compliance services to life sciences companies and their service providers. He helps them comply with the myriad of state, local and federal laws, regulations and guidances that apply to their businesses. Contact him via email at Darshan@conformlaw.com, Tel: + 215-703-7842 or twitter @FDALawyers

Deepak Nihalani PhD is Research Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He holds numerous editorial peer review and board positions and has been published in several research publications.

Have your say: How successful has the translational research model been in Europe compared to the US?