Spotlight on... tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that affects over 8 million people in the world. In our latest 'spotlight on', Stop TB UK's Matt Oliver provides us an overview of TB, including the symptoms, current drugs available on the market and how the pharma industry can help support patients.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium mycobacterium tuberculosis and transmitted via aerosol droplets. It most commonly attacks the lungs, but can affect any part of the body.

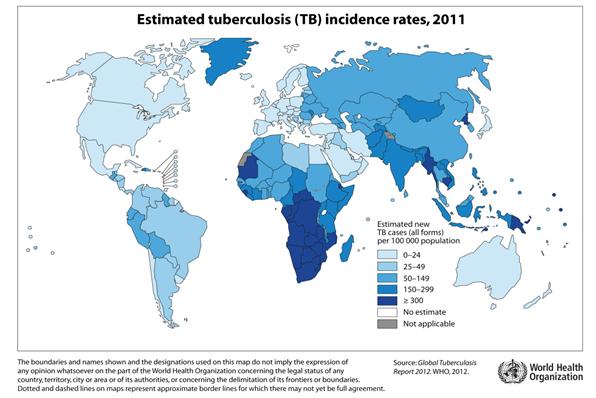

How many people have it?

An estimated 8.7 million people developed the active form of the disease in 2011 and 1.4 million people lost their lives. 1

However, roughly 1/3rd of the world's population is estimated to carry the bacterium. The human body can 'wall off' the disease, a condition known as 'latent TB'. Around 10% of everyone who has latent TB will develop the active form of the disease.2

The mechanism through which latent TB becomes active disease is largely unknown. However, immunosuppression (such as HIV infection) plays a key role; there have also been recent links between diabetes and TB infection. Development of the disease is also widely linked to certain social risk factors, notably drug or alcohol abuse, poor housing conditions, homelessness and imprisonment.3

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms vary widely depending on the location of the tuberculosis infection. The symptoms of active TB of the lungs are coughing, sometimes with sputum or blood, chest pains, weakness, weight loss, fever and night sweats.4

One problem is that TB is very difficult to diagnose, and as it is no longer common in the developed world, it often gets mistaken for other conditions.5

Tell us a little about the history

Tuberculosis has probably been with us since we stopped referring to the nearest tree as 'home'. As a result it's evolved with is, difficult to diagnose and treat, and adept at hiding in the body.

Throughout much of the intervening period, tuberculosis was commonly referred to as 'consumption' and had a heavy death toll. In the 19th century it became the 'White Plague' and was seen as something of a romantic disease. Chekhov, Keats, Chopin and later Orwell all lost their lives to the disease.

So heavy was the death toll caused by the disease down the centuries, that recent figures suggest that more people have died from tuberculosis, than all other contagious diseases in history, combined.9

How do you cure it?

Tuberculosis has always been hugely difficult to diagnose, let alone treat. Prussian physician Robert Koch discovered that the disease was caused by a bacterial infection in 1882, but it wasn't until 1944, with the isolation of streptomycin, that the first drugs were discovered.10,11

Preceding the discovery of streptomycin, there were a range of treatments developed: from the harmless to the lethal and from the mildly effective to those that almost certainly killed the patient. The most widely known was the sanatoria movement; patients were confined to bed rest and as much fresh air as possible.

"Tuberculosis has always been hugely difficult to diagnose, let alone treat."

Of course, the secret behind the sanatoria movement was that humans can independently recover from tuberculosis with no treatment at all, though the consequences of the disease are often severe and relapse was common.12

From the 1940s to the 1970s, several drugs were developed, with Isoniazid in 1952 representing a huge advance.

In 1960, Professor John Crofton, a TB expert at the University of Edinburgh, proposed that a combination of Streptomycin, PAS and Isoniazid, could completely cure TB if used from the outset of an individual case. This radical approach, which halved TB notifications in Edinburgh over a three year period, was initially met with disbelief. Sir John's findings were soon replicated in a large scale international trial, leading to the introduction of combination therapy as the global gold standard treatment. This method, which became known as the "Edinburgh Method", continues to influence the medical world today, including combined therapy for HIV.

Rifampicin in the 1970s was another step forward, but since then, few new drugs have been delivered.

Which leads us to the present day. A case of drug-sensitive tuberculosis currently takes in the region of 6 months to treat, with a daily combination of four drugs. Side effects are common.13

Unsurprisingly, treatment completion rates are often lower than the WHO's target of 85%, and many developed countries fail to hit that level.

More complex, drug resistant cases, can take up to 24 months, with dangerous, less-effective, more toxic drugs with potentially damaging side-effects, and often prolonged courses of intravenous injections.14,15

Challenges – drug resistance

A certain amount of tuberculosis bacteria are naturally resistant to one or another of the standard drugs prescribed. This is why it is important to use a combination of drugs. If treatment is stopped before all the bacteria are killed or if an incomplete or incorrect combination of drugs is given, the resistant bacteria can grow and cause TB to return in a drug-resistant form.

Just like any other form of the disease, drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is easily transmitted.

DR-TB represents an incredibly heavy burden to patients and health systems alike. South Africa, for example, spends 32% of its tuberculosis budget on DR-TB , but DR-TB only make up 2% of all the cases in the country.16

Challenges – inadequate treatments

The tools that are currently available to prevent, diagnose and treat TB are simply not up to the job. They were developed in an age before the HIV epidemic caused a huge upsurge in TB. They do not meet the treatment challenges posed by issues such as stigma and poverty – challenges that have contributed to the emerging threat of DR-TB.

The BCG vaccine was developed 90 years ago, and despite being the most widely used vaccine in the world, almost 9 million people develop TB each year. Worse, the BCG doesn't protect against the most common form of the disease: pulmonary tuberculosis.

Key front-line drugs mentioned above like Isoniazid and Rifampicin are over 40 years old. Whilst they remain our best weapons against the disease, treatment of the simplest cases takes six months and drug resistant cases can be much longer.

Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty, treatments are expensive to develop and get to market where returns are not guaranteed. Accordingly, there is very little financial incentive for manufacturers and pharmaceuticals to invest in developing critical new treatments and diagnostics that can quickly find people who are ill and treat them swiftly without side-effects.

Conclusion

The TB community must work in collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry to identify the obstacles to the development of new drugs and diagnostics and work together to overcome them.

We have the potential to end tuberculosis as a health threat in our lifetimes, but to do it we must mobilise the best research, the best policies and the best thinking to overcome our oldest of enemies.

References

1. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf

2. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/ltbiandactivetb.htm

3. http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/POST-PN-416

4. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Tuberculosis/Pages/Symptoms.aspx

5. http://c1280352.r52.cf0.rackcdn.com/FINAL_TB_VOICES_EUROPE_REPORT.pdf

6. http://museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/breath/tuberculosis-through-the-ages.html

7. Google Books

8. http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/aphorisms.5.v.html

9. http://www.theglobalmail.org/feature/plagued-tb-and-me/639/

10. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1905/koch-bio.html

11. http://www.biology-online.org/articles/aminoglycoside/streptomycin.html

12. http://www.lung.ca/tb/tbhistory/sanatoriums/

13. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Tuberculosis/Pages/Treatment.aspx

14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16468160

15. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/treatment/drugresistanttreatment.htm

16. http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0054587

The next article in this series will go live on 23rd August.

About the author:

Matt Oliver works for RESULTS UK as a Health Advocacy Officer working specifically on TB. He also leads the secretariat of Stop TB UK, a coalition of individuals and organisations who share an interest in tuberculosis. Before moving to RESULTS he spent some time working on malaria, and on health projects in Central America.

For more information visit: www.stoptbuk.org or email him on matt.oliver@stoptbuk.org.

In what ways can pharma and the tuberculosis community work better together?