Spotlight on actinic keratoses (also known as “sunspots”)

Our 'spotlight on' this month looks into the skin condition, actinic keratosis (also known as sunspots), which are premalignant but can develop into skin cancer. Kantar Health's Amy Sangway and Stefanie Beck highlight the importance of skin checks in early diagnosis and how further awareness of this condition is needed around the world.

What are actinic keratoses?

Actinic keratoses (AK), also known as 'solar keratoses' or 'sunspots,' are skin lesions that are caused by long-term UV damage to the skin. 'Actinic' and 'solar' come from Greek and Latin, respectively, and mean 'sunlight–induced' with keratosis meaning 'thickened scaly growth.'1

The term is often used in plural ('keratoses') as a person rarely has only one ('keratosis'); in fact, it is estimated that invisible (subclinical) lesions appear up to 10 times more often than visible lesions.2,3

"Actinic keratoses are a premalignant skin condition that can develop into skin cancer."

What risks are associated with actinic keratoses?

Actinic keratoses are a premalignant skin condition that can develop into skin cancer. The risk of an individual lesion developing into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma is estimated to range from only 0.025% up to 16% in different clinical studies.4 The New Zealand Dermatological Society estimates that the risk of squamous cell carcinomas occurring in a patient with more than 10 actinic keratoses is about 10-15%.5 In fact, the majority of squamous cell carcinomas, 65%, are estimated to begin as actinic keratoses.6

Where do they appear, and what do they look like?

Actinic keratoses most commonly appear on sun-exposed areas of the body. In some cases they can feel itchy or tender, be inflamed or rarely even bleed. Initially, a person may not be able to see actinic keratoses as they are so small, but they can be felt as rough spots, commonly described as feeling like 'sandpaper.'7

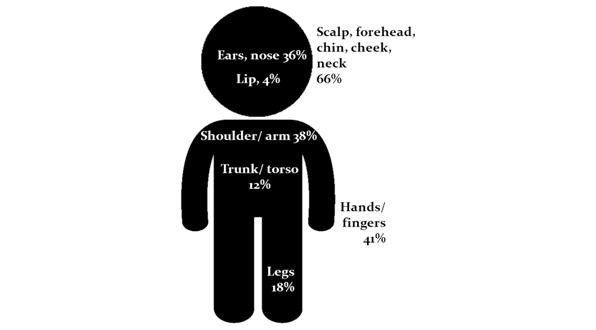

Figure 1: % of patients receiving treatment for AK at different locations8

Our survey conducted in Australia in 2007 showed that two-thirds of patients treated by a GP for actinic keratoses were treated on their scalp, forehead, chin, cheek and neck. Other common body areas for receiving treatment for actinic keratoses were hands / fingers (41%), shoulder / arms (38%) and ears / noses (36%), followed by legs (18%) and trunk / torso (12%). Some patients also received treatment for actinic keratoses on their lips (4%).8

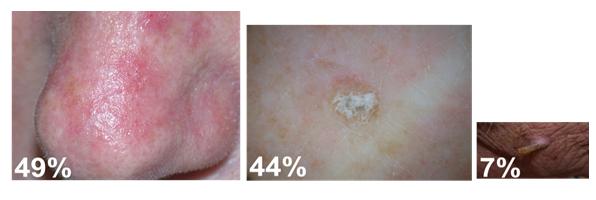

Figure 2: Appearance: % of treated AK.8 Images are published with the permission from the New Zealand Dermatological Society Incorporated

The study also looked into the appearance of actinic keratoses and found that almost half of actinic keratoses (49%) treated were flat in appearance, a large proportion (44%) were 'raised' and only a minority were with a cutaneous horn.8

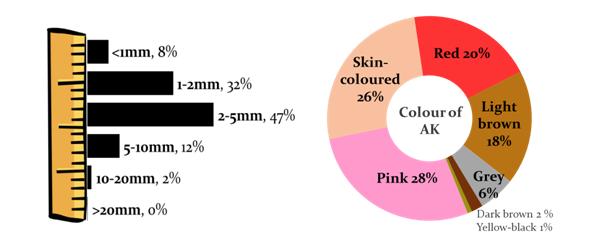

The majority of AKs were between 1 and 5mm in size (79%) and were pink (28%), skin-coloured (26%) or red (20%).8

Figure 3: % of AK by size and colour8

Who is it likely to affect?

Prevalence of actinic keratosis is related to cumulative sun exposure and thus is more common in countries located close to the equator and in people who work outdoors.9

Prevalence estimates in different countries:

• Australia: Between 40% and 60% of Australians aged 40 years or older10

• UK: More than 23% of the population aged 60 or older (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence)11

The prevalence of actinic keratosis is also much higher in individuals with fair skin, especially if combined with red hair or blue eyes, freckles and in individuals that burn easily in the sun. It is lower in individuals with darker skin types.11 Although occasionally actinic keratoses can occur in younger people; it is most common in those aged 50 years or older.10

"As with skin cancer prevention, protecting one's skin from the sun will help reduce the risk of developing actinic keratoses."

How can it be prevented?

As with skin cancer prevention, protecting one's skin from the sun will help reduce the risk of developing actinic keratoses. Typical prevention guidelines (as advertised on the skin cancer foundation website) recommend the following actions:12

• seek the shade

• use water-resistant, broad-spectrum (UVA / UVB) sunscreen with a high sun protection factor

• apply sunscreen 30 minutes before going outside and reapply every 2 hours or after swimming or excessive sweating

• cover up with clothing, a hat and sunglasses

• avoid tanning and UV tanning booths

Public awareness campaigns promoting sun protection have been running for the last two decades, such as the iconic and successful 'slip slop slap' campaign that started in the 1980s, and most Australians are well informed on this matter.13

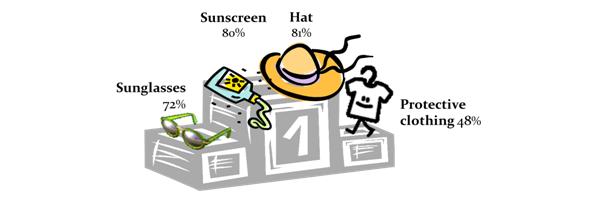

In 2010, our survey amongst 1,200 Australians aged 40 years and older showed that most participants typically use some form of sun protection, most commonly a hat, sunscreen or sunglasses (see figure 4).14

Figure 4: % of Australians using forms of sun protection14

Another step in prevention / early detection of actinic keratoses and skin cancer are skin checks. This is particularly important as sun protection has not always been as widely used as it is nowadays, and most of the sun damage of the current AK 'generation' already happened many years ago.

Figure 5: % of Australian having been to a doctor for a skin check-up or checked their skin themselves14

Our survey, conducted amongst 1,200 Australians aged 40 years and older, revealed Australians are less compliant with skin checks than with sun protection, with only 36% of respondents having been to a doctor for a skin check in the previous 12 months. Meanwhile, 62% of Australians have checked their own skin in the previous 12 months.14 Self-examinations of the skin are recommended by healthcare professionals and official health associations, such as the Australasian College of Dermatologists, in order to detect skin irregularities early. 15 However, our study also found that participants who check their own skin are not very confident that they would actually pick up sun-damaged irregularities that require further examination by a healthcare professional.14 Considering that Australia is the country with the highest incidence of skin cancer in the world and two in three Australians are estimated to be diagnosed with some form of non-melanoma skin cancer before the age of 70, it appears there is still a need to promote the importance and benefits of skin checks amongst the Australian population. 16, 17

The internet is a good source of information for people who are unsure about how to check their skin. An example is the step-by-step skin check guide available on the 'know your own skin' website (www.knowyourownskin.com.au).

"...Australians are less compliant with skin checks than with sun protection..."

A number of mobile phone apps are also available that help patients monitor changes in their skin and have useful functions such as reminders and the ability to take and upload photos that can be shown to physicians at the next skin check.

How is AK treated once it is detected?

The American Academy of Dermatology recommends that anyone with many AKs should see and get treated by a dermatologist.18 Actinic keratoses are the second most common reason to see a dermatologist in the US.19 The situation is different in Australia, where the incidence of actinic keratoses and skin cancer is very high and GPs frequently conduct skin checks and treat sun-damage-related skin conditions, both in general practice and in dedicated skin cancer clinics. A survey conducted in 2010, amongst 200 Australians who had undergone treatment for AK in the previous 2 years, revealed that patients were most commonly treated by GPs who do not work in dedicated skin cancer clinics (61%), followed by GPs working in dedicated skin cancer clinics (25%); only a small number was treated by dermatologists (8%) or other specialist physicians (6%).20

Treatments span surgical and non-surgical therapies such as cryotherapy and topical medications. The treatment length and frequency of application of available topical medications vary from treatment to treatment and range from once daily for 2-3 days to 3 times weekly for up to 16 weeks.21 Which treatment to choose is generally based on the number of lesions and the efficacy of the treatment.22

How can the pharmaceutical industry better support patients with actinic keratoses?

The pharmaceutical industry could play an important role in raising current levels of awareness of actinic keratoses (particularly in high-incidence countries), particularly in educating patients about the associated risks of actinic keratoses and the importance of skin checks in early detection. Patient education materials that help patients understand the available treatment options (types of treatments, application, treatment frequency and duration, effects on skin etc.) as well as advice on skin care during and post-treatment may also be useful.14, 23

References

1. British Association of dermatologists: http://www.bad.org.uk/site/794/default.aspx

2. http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/actinic-keratosis/what-is-actinic-keratosis

3. Berman B, Amini S, Valins W, Block S. Pharmacotherapy of actinic keratosis. ExpertOpinPharmacother 2009:10(18):3015-3031.

4. Glogau RG; The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Jan;42(1 Pt 2):23-4

5. http://dermnetnz.org/lesions/solar-keratoses.html

6. Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, Luque C, Eide MJ, Bingham SF, Department of Veteran Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial Group / Cancer. 2009;115(11):252

7. http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/actinic-keratosis/what-is-actinic-keratosis

8. Kantar Health, 2007. Survey amongst 35 GPs, involving patient diaries covering 334 patients treated for AK, 735 cases of treated AK in total

9. Frost CA, Green AC, Williams GM .The prevalence and determinants of solar keratoses at a subtropical latitude. Br J Dermatol. 1998 Dec;139(6):1033-9

10. Salasche SJ.Epidemiology of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. Jan 2000;42(1 Pt 2):4-7

11. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/solar-keratosis/Pages/Introduction.aspx

12. http://www.skincancer.org/prevention/sun-protection/prevention-guidelines

13. http://www.sunsmart.com.au/news_and_media/media_campaigns/slip-slop-slap/

14. Kantar Health, 2010. Survey amongst 1200 Australian aged 40 years and older

15. http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/public/a-z_of_skin-how_to_check_your_skin_moles.asp#03

16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australasian Association of Cancer Registries (2004). Cancer in Australia 2001. AIHW cat. no. CAN 23. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

17. Staples M., et. al. (2006). Non-melanoma skin cancer in Australia: the 2002 national survey and trends since 1985. Medical Journal of Australia 2006; 184: 6-10

18. http://www.aad.org/skin-conditions/dermatology-a-to-z/actinic-keratosis

19. Spencer JM, Hazan C, Hsiung SH, Robins P. Therapeutic decision making in the therapy of actinic keratoses.J Drugs Dermatol.2005;4(3):296–301

20. Kantar Health, 2010. Survey amongst 200 Australians treated for AK in the previous 24 months

21. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0901/p667.html

22. Gold MH. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. J Drugs Dermatol. Jan 2008;7(1):23-5.

23. Kantar Health, 2013. Survey amongst 12 Australian patients undergoing treatment for AK

About the authors:

Amy Sangway is a Director and Stefanie Beck is a Consultant at Kantar Health Australia. In the past 5 years, they have been involved in a number of market research engagements into solar keratoses, sun protection and skin check behaviour surveying various healthcare professionals, industry bodies, patient support groups, patients and members of the general Australian population.

How can pharma raise further awareness of skin checks?