Sitting uncomfortably? The UK’s PPRS and statutory schemes

As the pharma industry and the Department of Health prepare to negotiate on a successor to the 2014 Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS), Leela Barham considers whether the current PPRS and the statutory scheme run effectively in parallel.

The UK has run two parallel approaches to regulating the price of branded medicines paid for by the NHS for some time. The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) is the voluntary scheme, with all those companies not in the PPRS automatically under the statutory scheme.

Statutory scheme

Today’s statutory scheme originated in a difficult time for pharma price regulation. It is based on legislation from 2007 and 2008 following a disagreement between the Department of Health (DH) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) on whether GSK had delivered the savings that it should have done according to the PPRS that was in place at the time. The High Court found in GSK’s favour, prompting the government to serve notice on the PPRS, but also to introduce the statutory scheme.

The statutory scheme controls headline prices, but not net hospital prices. The DH has also consulted on, but not yet put in place, measures to capture average selling prices (ASP) in hospitals. The last headline price cut under the statutory scheme was 15% on maximum prices charged to the NHS on 1 December 2013. Unlike the PPRS, the statutory scheme could, in theory, be subject to frequent change, so future price cuts are a risk. The last consultation, in September 2015, mooted further headline price cuts, which could be up to 30%.

2014 PPRS

The 2014 PPRS has its roots in a period of austerity for the UK, departing from the headline price cuts of PPRS agreements of the past and, instead, adopting what are termed ‘PPRS payments’. All PPRS member companies make these payments to the DH.

PPRS payments are triggered whenever the NHS spends more than an agreed amount on branded medicines. It’s complicated, though, because those payments relate not only to how far above allowable growth rates spend goes (negotiated and agreed upon by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry [ABPI] and DH as part of the negotiation of the 2014 PPRS) but also to exemptions, for example, for parallel imports (PIs). PIs change in response to exchange rate changes, and we’ve seen those of late, especially as a result of Brexit. Plus the final amounts actually paid by companies reflect their sales, adjusted for the sales of any ‘new’ medicines launched during the scheme. (And let’s not get into where the PPRS payments actually go: no-one really knows, with the exception of Scotland, which uses them for a new medicines fund).

The case for two schemes

The basic rationale for having two schemes seems sound – i.e. to ensure that the government has a way to intervene, when the voluntary PPRS is not taken up, in a market that sees many market failures. Presumably both industry and government have enjoyed benefits from PPRS over and above the statutory scheme, on the basis of revealed preference.

Companies can, in effect, ‘quit’ the PPRS (although industry as a whole cannot easily do this because it would rely on all PPRS member companies agreeing to quit at the same time – an unlikely scenario), and the government can give notice on it, just as it has in the past.

Differences

So, does it matter that the schemes are now more divergent than before? There is a natural question about which scheme is more favourable for companies and, from the government side, which scheme is able to secure the best deal for taxpayers. That is not just a policy question but, for companies, a very real commercial one. Many companies will run internal exercises to figure out which is the better deal for them. The DH has said, in a Freedom of Information response, that five companies had left the 2014 PPRS up to the end of May 2016 and, although that may reflect a number of reasons, perhaps the relative attractiveness of the PPRS versus the statutory scheme was one of them? That leaves 162 companies still in the PPRS.

Proposals to bring more alignment

There have been DH proposals to potentially bring about more alignment. The DH consultation on changes to the statutory scheme was published in September 2015. The DH said that the statutory scheme was producing lower savings relative to the PPRS: that gap was also expected to widen over time (although it is not clear how Brexit could affect things). It also wanted to promote a more level playing field between companies – ostensibly to encourage companies to remain in the PPRS so that it could deliver its objectives of stability and predictability to both government and industry.

The DH proposed changes that amounted to either more of the same in the statutory scheme, with further headline price cuts (20%-30%), or companies would need to pay a percentage of their sales back to the DH (10%-17%). The latter seemed – on the face of it as it’s not been implemented – to be bringing in more of a 2014 PPRS style of approach. The consultation closed in December 2015 but, so far, the DH has not published any response.

A policy question

Whether the differences matter or not may become a more important question as the industry and the DH prepare to negotiate on a successor to the 2014 PPRS.

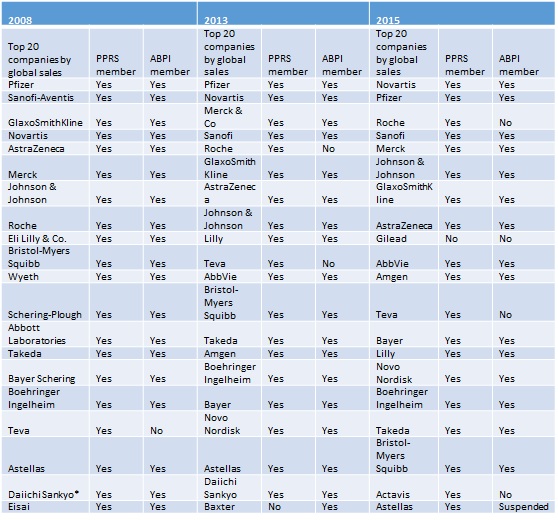

Looking at the top 20 pharma companies by sales in 2008 (the year before the 2009 PPRS was implemented and when negotiations would have been in full swing), in 2013 as the 2014 PPRS was being negotiated versus the top 20 pharma companies by sales in 2015 (the latest data), there is naturally some overlap (Table 1).

However this time it is different. There are some new names and one of those – Gilead, in sixth place with global sales of over US$31,151 million in 2015 – is not a member of the PPRS. Taking a UK perspective, Gilead rises up the ranking to number five in terms of spend in 2014 across the primary and hospital sectors, and fourth if just hospital spend is considered, according to DH analysis.

Gilead has secured its UK position in large part due to sales of Harvoni and Sovaldi for hepatitis C, and Truvada for HIV infection. Gilead has faced a great deal of scrutiny for its high pricing of Sovaldi, in particular, although there is a sense that it is a real breakthrough in therapy. In England, Sovaldi received a positive recommendation from NICE but, given its significant budget impact, adoption has been delayed. Gilead has still secured a 7% increase in UK hospital drug spend between 2013 and 2014, even with that delay.

As it is not in the PPRS, Gilead is subject to the statutory scheme. The company successfully challenged the DH’s plans for a 15% price cut for its products under European procurement law. The DH states that only 19 of those companies under the statutory scheme have taken that price cut, out of 125 companies. Many will not have had to, because they are exempt due to their small size, with sales income of less than £5 million and/or low cost presentations of less than £2 or, as is the case with Gilead, where there is a framework agreement already in place that pre-dates the date set for price cuts. It’s unclear whether or not the latter will prevent future price cuts or not under the statutory scheme, but it is likely that the DH is wise to this now.

Representation of industry

There is a difference in membership of the ABPI now, too, which has the (perhaps unenviable) pleasure of representing the industry in negotiations with the DH on the successor to the 2014 PPRS. All but one of the companies in the top 20 in 2008 were members of the ABPI. Now, four in the top 20 are no longer members (a further company has been suspended from membership for breaches of the ABPI code). That’s two less than in 2013 as well.

Table 1.

Sources: Contract pharma; DH; ABPI; PMLive; DH; ABPI; Ranking the brands; DH; ABPI.

Three of the top 20 companies that are not members of the ABPI are members of the Ethical Medicines Industry Group (EMIG). EMIG is a comparatively young organisation, operating as a trade organisation since 2005, as opposed to the ABPI, which was founded in 1891. Although the ABPI still represents companies that supply 90% of all medicines, it doesn’t speak for all of the big hitters, at least by global sales. Getting a consistent message to the government on the future of the PPRS is likely to be harder now than in the past (if, indeed, it has ever been possible).

Towards more similarity?

The two schemes, acting in parallel, have, in large part, helped provide a proportionate approach to regulating prices, with many small companies in the statutory scheme and, until recent years, the largest companies in the PPRS. Now that situation has changed.

So the question facing the negotiators is whether having two different approaches is securing the best deal, and the fairest playing field? Or would two schemes with more similarities work better, by securing the best of the PPRS and keeping the safety net of the statutory scheme?

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more from Leela Barham: