What is ‘affordable’? The reality of the PPRS

In the second in her series of five articles, Leela Barham examines to what extent the second objective of the PPRS – to keep the branded medicines bill within affordable limits – has been met.

The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) is a voluntary agreement between the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) and the UK government, represented by the Department of Health (DH). It’s second objective is to ‘support the NHS by ensuring that the branded medicines bill stays within affordable limits’. With less than 18 months to go until the current PPRS ends, and as negotiations are about to start on the next scheme, has it delivered on affordability?

PPRS payments triggered when spend above allowed rates

The 2014 PPRS made a big departure from previous schemes and essentially provided a limit to NHS spend on branded medicines sold by member companies. Member companies have to pay back to the DH when the NHS spend goes above agreed growth rates in the branded medicines bill. And they have paid a considerable amount: £1.87 billion up to the first quarter of 2017.

Some may say that limiting the amount the NHS spends on branded medicines is good enough to keep the branded medicines bill affordable, since it is PPRS member companies that take the risk that the bill is higher than the DH would like.

At the same time, though, there are exclusions from the PPRS. Some drugs are excluded because they are parallel imports or centrally tendered. Then there are those for which the voluntary PPRS does not apply. Despite the fact that the PPRS covers the vast majority of spend on branded medicines by the NHS – the ABPI says it represents companies that account for around 80% of spend, and it’s likely ABPI member companies are PPRS member companies too – the PPRS is simply not comprehensive. Companies that choose not to be in the PPRS are subject to other government legislation, and their drug prices – and spend on them - are controlled separately to the PPRS. That means pressure from growth in medicines spend on the NHS still remains, albeit eased by the 2014 PPRS.

What is ‘affordable’?

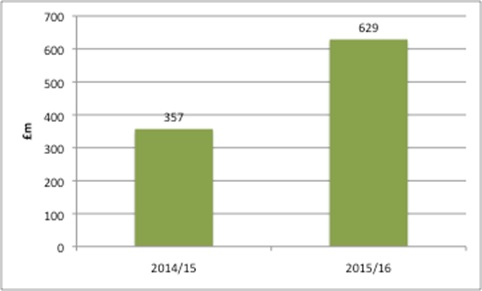

Leaving aside the political and economic decisions on the funding of the NHS, there is the issue of perception of what’s affordable, from those in the NHS and the wider system. The NHS as a whole spends around £16 billion a year on drugs: £9 billion via GP prescribing and £7 billion in hospital treatment. NHS England (NHSE) spends around £3.5 billion via its specialised commissioning. While it is (very) small in the grand scheme of things, NHSE rarely (never?) recognises the millions it has received from PPRS payments, allocated in advance by the DH as part of the Mandate (this sets objectives for the NHS to meet) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PPRS payments allocated to NHS England, 2014/15 and 2015/16

Source: Data from DH for 2014/15 and 2015/16

NHSE not only pays for drugs as part of its own delivery of specialised services, but also doles out the money to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), which pay for local NHS services and primary care medicines too.

The introduction of a budget impact test – where companies whose new medicines could cost more than £20 million a year in any of the first three financial years after launch, even if they are deemed cost-effective by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) could face a negotiation with NHSE – suggests NHSE still does not think the bill is always affordable.

The budget impact test hasn’t yet been implemented, and the ABPI is seeking a judicial review on the change.

It’s clear that the PPRS – and the more than £1 billion it has put back into the NHS – was not able to push back on further changes to keep the branded medicines bill affordable, at least from the NHSE perspective. That could be seen as a big failure of the PPRS, or the rise in influence of NHSE; it’s probably both.

Why is £20 million unaffordable?

The budget impact test picks £20 million as the threshold, a figure chosen by NHSE. That suggests this is the level where NHSE becomes concerned about how it can accommodate the drug in its spending plans. It does not imply that the NHS would not pay £20 million in a given year, but that it would require specific efforts to do so. Those efforts could take the form of a discount, or phased access in order to smooth spend.

A review of the positive decisions made by NICE between June 2015 and June 2016 suggested that 20% of NICE-approved drugs would be subject to negotiation at a £20 million threshold. There is no rationale for the choice. It does not relate to the growth in how much is allocated to NHSE by the DH, nor to any clear understanding of what else would need to be stopped to free up funds.

For example, £20 million doesn’t tally up with NICE’s resource impact forward planner for Technology Appraisals. NICE provides this tool to help the NHS plan for the resource impact of the drugs it assesses. That tool operates the following definitions:

- Cost saving – anticipated net cost is less than £0

- Cost neutral – anticipated net cost is less than £1 million

- Low cost – anticipated net cost is between £1 million and £15 million

- Medium cost – anticipated net cost is between £15 million and £30 million

- High cost – anticipated net cost is greater than £30 million

Under these categories, £20 million is medium cost, and certainly not high cost. While NICE doesn’t define affordability – and nor should it – logically, it is high-cost drugs that are more likely to be unaffordable.

It also has the knock-on impact of limiting the degree to which anyone can identify, using NICE estimates, which drugs may be subject to the budget impact test, if it is implemented following the legal challenge.

The bigger picture

With the tax-funded NHS there is the option – in theory at least – of raising more funds and some of that could be spent on medicines. That brings into play all sorts of political decisions, influenced by the desire to win votes, the state of the economy and the interaction with taxation.

Has the PPRS kept the bill affordable?

It cannot be disputed that the PPRS has made a major contribution to affordability: the NHS branded medicines bill would have been, by definition, over £1.87 billion higher without the agreement, assuming no other changes. It is also true that the PPRS has helped to keep the share of NHS funding for medicines stable, at around 12%, which is about the same from 2010/11 to 2015/16. However, it has not addressed NHSE affordability concerns successfully.

So, it depends on your perspective whether the PPRS has kept the branded medicines bill affordable: glass half full or half empty. Inevitably, though, as the successor to the 2014 PPRS is drawn up, affordability, and how the PPRS can contribute towards that (hazy) goal, will be in the sights of the DH, with NHSE paying close attention. Or will there be a break from the past, and NHSE could be part of the negotiations?

Read the first part of this five-part series on the PPRS:

Unstable and unpredictable? The reality of the PPRS

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.