NICE’s track record in cancer drugs: the impact of the CDF and interim funding

Leela Barham looks back to before the Cancer Drugs Fund and how recommendations have changed through CDF 1.0 and CDF 2.0 to explore it's success.

Cancer drugs and the decisions made by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have been subject to much scrutiny and more than a little controversy.

There’s been much debate too. All of this has led to some policy fudges through the introduction of a Cancer Drugs Fund.

The Fund first came into being in 2010 before going through a reform in 2016. By 2019, we can look back and see what the impact of the Fund has been on NICE recommendations using NICE’s new downloadable excel sheet on cancer Technology Appraisals (TAs).

Pre-CDF

Before 2011 only some cancer drugs were looked at by NICE. But those that were looked at didn’t always get approval. Headlines were being made and those headlines prompted political action. In 2010 the Conservatives pledged to introduce a Cancer Drugs Fund to provide money solely for cancer drugs. With the Conservatives winning the 2010 general election the Fund moved from political promise to a real-life fund, part introduced in 2010 before being fully implemented in April 2011.

CDF 1.0

The original Fund was run by NHS England. The fund’s expenditure rose over time, from £200 million in 2011/12 to over £400 million in 2014/15. Debate raged about just how decisions were made and whether it was a good use of money. Questions were asked too about what it meant for NICE; in essence, a politically driven fund administered by NHS England was overruling NICE’s decisions.

CDF 2.0

A new and improved Fund was set up and began in July 2016. Big changes were the repositioning of the Fund under NICE, as well as new financial components that would keep the fund within £340 million a year. CDF 2.0 was positioned as a fund to help explore whether a cancer drug could ever become cost-effective over time by collecting evidence and allowing for another review by NICE once that evidence was collected. In essence, the Fund gives interim funding to help find out if a cancer drug should be available on a routine basis in the future, or not.

NICE impact?

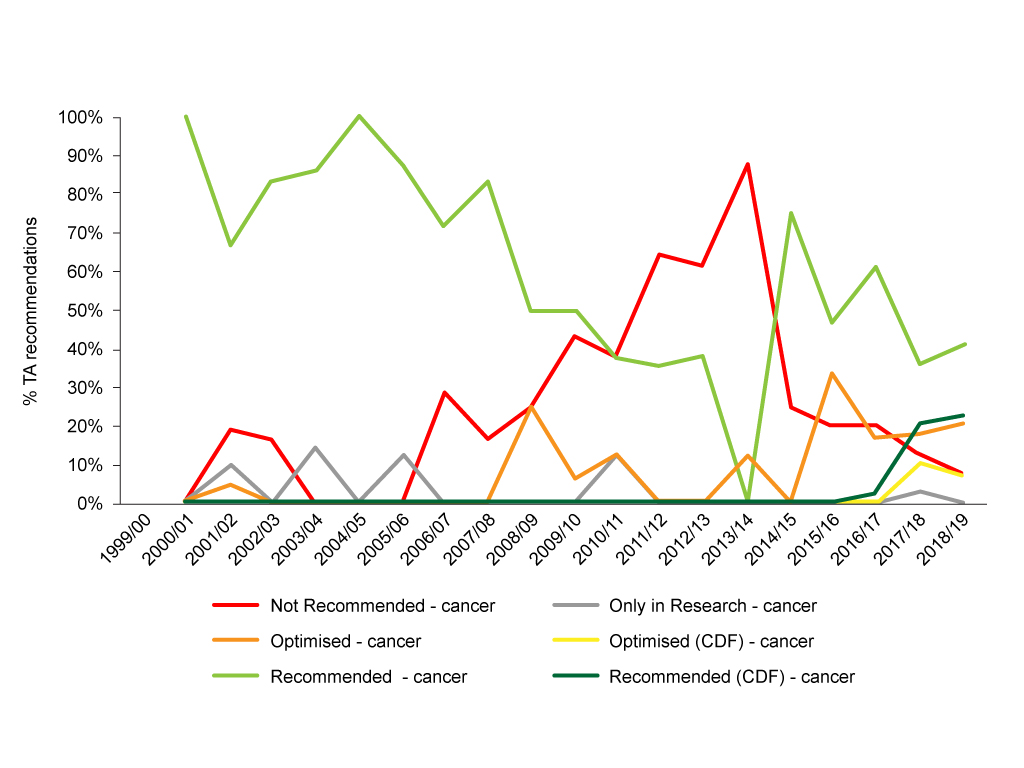

It’s clear that trends in NICE recommendations have changed over time. Particularly marked is a fall in outright negative recommendations (figure 1).

Figure 1: Trend in NICE TA recommendations for cancer drugs, 1999/00 to 2018/19

Source: Analysis of NICE data.

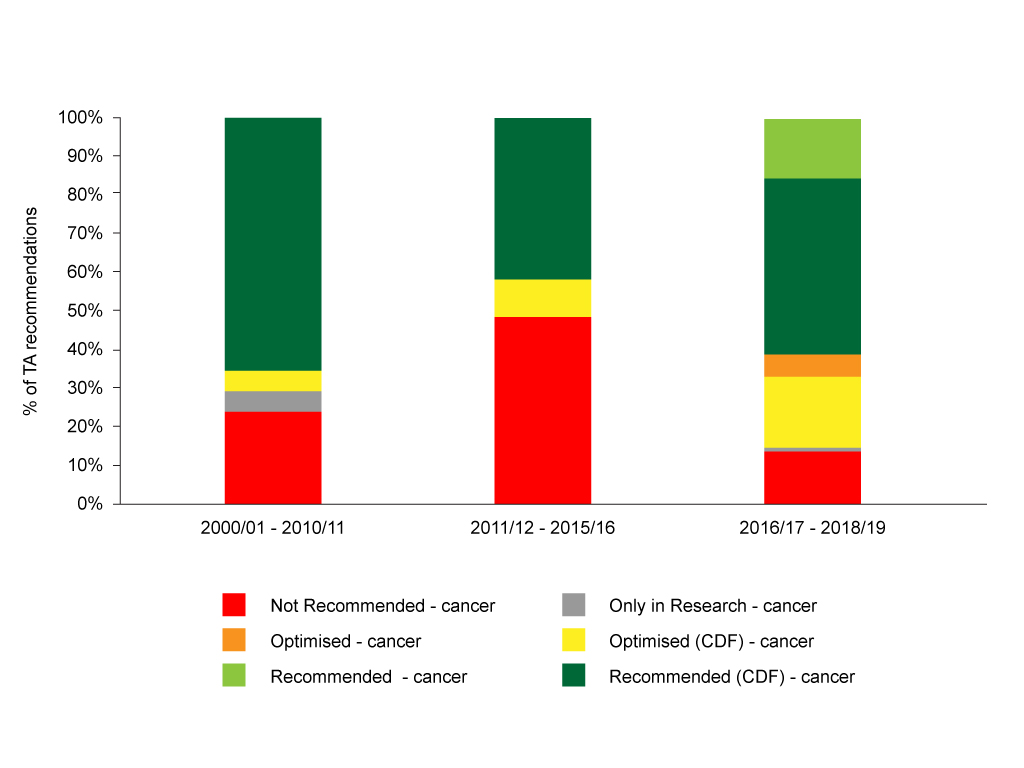

Yet looking at recommendations in this way it is hard to determine the impact of CDF 1.0 and CDF 2.0. For that, we can bring together recommendations made pre-Cancer Drugs Fund, during the lifetime of CDF 1.0 (almost, NICE data is by financial year, so we can look at 2011/12 through to 2015/16) and CDF 2.0 (2016/17 onwards) (figure 2).

Figure 2: NICE TA recommendations pre-CDF, CDF 1.0 and CDF 2.0

Source: Analysis of NICE data.

Cutting the data by the time periods that (roughly) align with the pre-CDF, CDF 1.0 and CDF 2.0 time periods illustrates that the CDF 2.0 has seen a marked change with fewer rejections. There is, of course, use of the new recommendations introduced as part of CDF 2.0, ‘optimised in the CDF’ and ‘recommended in the CDF’. Optimised means, in essence, use in some subgroups, and both 'optimised in the CDF' and 'recommended in the CDF' are forms of interim funding.

Full impact of CDF 2.0 needs further work to explore

The full impact of CDF 2.0 needs further digging into the NICE data to explore, for example, the decisions made as part of cancer drug reviews, as well as looking in particular at the new cancer drugs that have been looked at for the first time. Not only that, but the degree to which the evidence or the price has changed over time for cancer drugs. It’s not clear whether, for example, NICE is now able to say yes because the uncertainties relating to the clinical benefit have really been addressed (I have doubts about this, data from the Fund is limited, and that’s backed up by academic research), nor whether companies have gone back to the drawing board on price (and maybe they’ve done that a few times during the time at which NICE has looked at their drug), or some combination.

Cancer Research UK have suggested that CDF 2.0 is a success on the basis that drugs paid for under CDF 1.0 were reviewed and NICE approved almost all of them. It might be useful to look to others – who are independent – to really answer the question of whether it is a success, or not, as well as bring together the evidence base in a more systematic way.

A wider role for interim funding?

Sometimes it’s not just a NICE yes that we need to consider, but a bigger question of just how best to spend limited NHS funds. That means not just thinking about cancer, but all other patients too. With a review of NICE methods, including for TAs, ongoing, could now be an opportunity to redress the focus on cancer and consider interim funding for other promising drugs, which may not yet be able to show that they are cost-effective?

For a more general overview of NICE’s stats on Technology Appraisals over its 20-year history, read our article on NICE's numbers at 20.

About the author

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, working on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally, working on the economics of the pharmaceutical industry. Leela worked as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care on the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).