Inter partes review in generic drug litigation—Why the USPTO should exercise its discretion to deny IPR petitions in appropriate Hatch–Waxman Act disputes

The Hatch–Waxman Act, enacted nearly 30 years ago, reflects a negotiated balance between making generic drugs more readily accessible and protecting the significant investment made by brand name pharmaceutical companies. More recently, Congress passed the Leahy–Smith America Invents Act ("AIA"), including the new Inter Partes Review ("IPR") procedure, which as applied to patents involved in generic drug litigation, threatens to disrupt the balance achieved by the Hatch–Waxman Act. The IPR rules, however, provide the USPTO with broad discretion to deny initiation of IPRs. Due to the unique framework of the Hatch–Waxman Act and its intended goal of balancing the needs of branded and generic drug manufacturers, the USPTO should exercise its discretion and decline to conduct IPRs directed to patents involved in appropriate Hatch–Waxman patent challenges.

The 2011 Leahy–Smith America Invents Act ("AIA") has provided an expedited Inter Partes Review ("IPR") process to challenge issued patents before the USPTO. The IPR procedures, however, may not be well suited for certain cases involving patent disputes relating to the right to sell generic drugs governed by the Hatch–Waxman Act, passed in 1984. Specifically, the use of IPR in such disputes is likely, in many cases, to disrupt the carefully balanced framework of compromises underlying the Hatch–Waxman Act, especially those provisions that provide for a 30-month postponement of FDA approval of a generic's Abbreviated New Drug Application ("ANDA"), to allow the patent issues to be resolved in court before generic competition begins. Accordingly, the USPTO should exercise its discretion and decline to institute IPR proceedings in appropriate ANDA disputes.

The competing statutes

The Hatch–Waxman Act sought to balance the competing interests of pharmaceutical innovators and their generic competitors. On one hand, the statute shields development of generic drugs from patent infringement liability if such activity is reasonably related to securing FDA approval. On the other, the statute requires a generic drug maker seeking FDA approval to market before patent expiration to file a so-called "Paragraph IV Certification," asserting that the innovator's patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed, and to send notice of its views and the reasons therefor to the patent owner. The Act then permits the patent owner to file suit for infringement and further provides for a stay of FDA approval of the generic product, usually for a period of 30 months. The stay permits generic manufacturers to resolve the patent issues without incurring liability for damages and permits judicial resolution before the innovator's market is radically disrupted by potentially unlawful generic competition.

More recently, Congress passed the AIA in an attempt, inter alia, to reduce costly district court litigation and address a number of perceived deficiencies in the patent law. To accomplish this, Congress reinvented inter partes reexamination into what is now known as IPR. IPR is an adjudicative proceeding before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ("PTAB") rather than a traditional patent examination. It permits anyone other than the patent owner to challenge a patent's validity for alleged obviousness or lack of novelty based on patents or printed publications. Like inter partes reexamination, the IPR petitioner is foreclosed from raising, in court, invalidity challenges that were raised or could have been raised in its IPR, which may discourage use of the procedure by some generic manufacturers. Unlike inter partes reexamination, which generally took several years to reach appeal at the USPTO making that procedure unattractive to generic companies, IPR is a relatively fast proceeding, concluding in 12–18 months. There is no presumption of validity, and limited discovery is allowed, possibly making IPR an attractive option to generic manufacturers in some cases. If the petitioner or real party in interest files an invalidity challenge in district court on or after the date on which the petitioner files a petition for IPR, the district court case is automatically stayed. Otherwise, the decision on whether or not to stay court proceedings is left to the court's discretion.

The Problems

IPRs can significantly complicate the landscape of Hatch–Waxman litigation, particularly when the IPR petitioner has filed, or is in the process of preparing, an ANDA containing a Paragraph IV Certification. Several observations illustrate this point:

• ANDA Defendants Circumvent Hatch–Waxman—Anyone can file an IPR as long as they did not previously file a civil action challenging validity of the patent and were not served with a civil complaint alleging infringement of the patent more than one year earlier. The policy behind the bar is to preserve judicial resources and force a challenger either to sue in district court, or to seek IPR in the USPTO, but not both. Yet, in Hatch–Waxman cases, the filing of a Paragraph IV Certification with an accompanying notice letter may not automatically bar an IPR, even though it plainly initiates district court litigation, and is thus equivalent in this regard to filing a civil action. Indeed, other portions of the AIA addressing "supplemental examination" treat the filing of a Paragraph IV Certification as the functional equivalent of a civil action. Allowing IPRs on patents previously addressed in a Paragraph IV Certification would enable generic companies seeking IPR to benefit from the provisions of the Hatch–Waxman scheme while possibly depriving a branded company of its right to litigate the patent dispute in district court.

• Branded Drug Manufacturers May Lose 30-Month Stay—An increasingly important aspect of IPR practice is the ability to stay district court litigation during an IPR. Such stays are granted to promote judicial efficiency, avoid duplication of effort, and conserve the parties' resources. The IPR stay provisions are, however, unworkable in many ANDA litigations because of the 30-month stay of FDA approval. Suspending the litigation for 12–18 of the 30 months of the stay of FDA approval will usually assure that the court case cannot be finished before FDA approval.

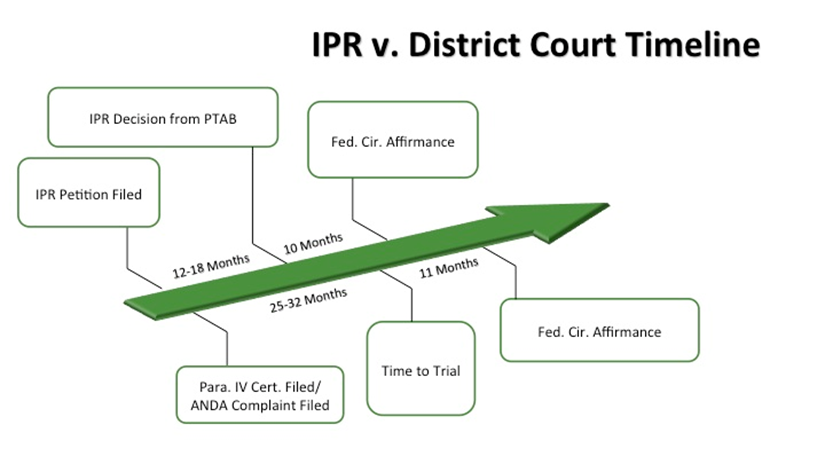

• Conflict of Decisions—As recently seen in Fresenius USA, Inc. v. Baxter International, Inc., 721 F.3d 1330, reh'g denied, 733 F.3d 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2013), a USPTO unpatentability decision that is affirmed as final before completion of appeals in a related, but conflicting, district court judgment may trump the district court's validity determination. The USPTO's unpatentability decision may render the district court's validity decision, and all the work that went into it, moot simply because the USPTO action was finalized first. And as the graph below illustrates, this is likely to occur in many ANDA cases. Statistically, USPTO IPR decisions resolved in 12–18 months are likely to reach the Federal Circuit before district court decisions, where the average time to trial in courts with lots of ANDA litigation ranges from 25–32 months.

The Solution

In light of these important considerations, the PTO can and should exercise discretion to decline to institute IPRs in appropriate ANDA disputes.

"IPRs can significantly complicate the landscape of Hatch–Waxman litigation..."

Neither the AIA nor its legislative history suggests any absolute right to IPR. The statute states when the USPTO may not authorize an IPR, but does not provide that it must institute an IPR under any circumstances. It follows that the absence of any affirmative requirement to institute IPR effectively grants the USPTO broad discretion to deny institution of an IPR on any ground. The non-appealable nature of the USPTO's institution decisions confirms this discretion.

Moreover, as required by Hatch–Waxman, ANDA disputes must be heard by the district court. Consequently, there will necessarily be duplicative efforts between the district court and the PTAB. Duplication of effort may counsel against instituting IPRs in certain circumstances involving ANDA disputes. Indeed, the PTAB has stated that it considers economy and the integrity of the patent system in fashioning IPR procedures, and similar considerations may justify refusal to institute IPR in appropriate ANDA cases. Cf. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. v. Progressive Casualty Ins. Co., CBM2012-00003, Paper 7 (PTAB Oct. 25, 2012). Further, the time and effort usually required to fully and fairly resolve these very complicated ANDA disputes in court—often more than 25 months—strongly suggests the inadequacy of even an 18-month period. The AIA provides the USPTO with the discretion to deny IPRs if it appears a particular case cannot be resolved quickly enough or would overburden the Board.

Finally, discretionary abstention from exercising the power to act, when doing otherwise is likely to upset ongoing proceedings, is a well-established principle in American jurisprudence. See, e.g., Colorado River Water Conservation Dist. v. United States, 424 U.S. 800 (1976) (abstention from exercising jurisdiction in concurrent proceedings may be warranted based in part on "(w)ise judicial administration, giving regard to conservation of judicial resources and comprehensive disposition of litigation"). As discussed above, conflicting validity determinations between the USPTO and district courts, and the sensitive time period due to the 30-month stay of ANDA approval, warrant careful consideration by the USPTO of the wisdom of proceeding with an IPR in certain circumstances involving ANDA litigation.

Conclusion

The conflicting Hatch–Waxman and AIA schemes present strong arguments against instituting IPR proceedings in many generic drug patent disputes. Moreover, by granting the USPTO broad discretion to decline to institute an IPR, Congress has created the statutory framework allowing the USPTO to permit such validity disputes to be litigated in the district courts, as intended by Hatch–Waxman. Hopefully, the USPTO will do so in appropriate cases.

This Article is for informational and educational purposes only, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and may be considered advertising under applicable state laws. This Article reflects only the current views of the authors and is not attributable to Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP, or the firm's clients.

About the authors:

Aaron V. Gleaton is an associate at Finnegan. He focuses on patent litigation in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology areas, with particular emphasis on ANDA cases in U.S. district courts. Mr. Gleaton can be reached at 202.408.4327 or aaron.gleaton@finnegan.com.

Sanya Sukduang is a partner at Finnegan. He concentrates on patent litigation before the federal district courts and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, primarily in the areas of biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, biologics, and medical devices. He has extensive experience in ANDA cases. Mr. Sukduang can be reached at 202.408.4377 or sanya.sukduang@finnegan.com.

Howard W. Levine is a partner at Finnegan. His practice concentrates on biotechnology and pharmaceutical patent litigation before the federal district courts and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Mr. Levine has extensive experience in ANDA cases. Mr. Levine can be reached at 202.408.4259 or howard.levine@finnegan.com.

Charles E. Lipsey is a partner at Finnegan. His practice focuses on intellectual property litigation, particularly patent infringement litigation. He has handled cases covering a diverse spectrum of mechanical, chemical, and electrical technologies, with an emphasis on cases involving biotechnology and pharmaceutical chemistry. Since joining Finnegan in 1978, Mr. Lipsey has amassed a wealth of experience in patent infringement litigation, patent arbitration proceedings, and patent interferences. He can be reached at 571.203.2755 or charles.lipsey@finnegan.com.

Closing thought: Should IPRs be denied in cases involving Hatch-Waxman disputes?