How old is your heart?

Rebecca Aris interviews Professor Rod Jackson

University of Auckland

We interview Professor Rod Jackson of the University of Auckland around determining a person’s cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk with the use of heart calculators, which can record just how old their heart really is.

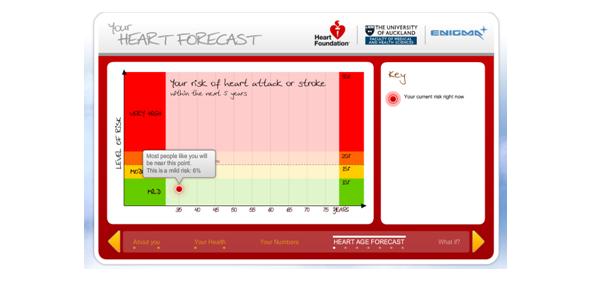

Patients can present with many cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, and assessing and measuring them can result in confusion for both patients and physicians. A straightforward way of measuring CVD risk is with a simple tool that gauges how old your heart is. The University of Auckland helped to co-create ‘Your heart forecast’, a tool that enables users to input some personal data and discover how old their heart is. The tool also allows users to look ahead and see how simple lifestyle changes could alter their CVD risk in the future for better or worse.

We speak here with Professor Rod Jackson on the importance of turning our attention to heart age and why it should be the key determinant in treatment decisions.

Interview summary

RA: Professor Jackson, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed today, could you please start by telling us more about the New Zealand risk-based clinical guidelines for managing CVD risk?

RJ: The main principle of the NZ guidelines is that treatment should be determined primarily by a patient’s predicted (multifactorial) risk of a CVD event over the next 5 years, rather than the level of any individual risk factor. Moreover, the intensity of treatment (e.g. number and doses of drugs) should be directly proportional to the magnitude of the short-term (5-year) multifactorial risk. Dichotomous ‘syndromes’, such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia are not considered to be clinically relevant and treatment thresholds based on blood pressure or lipid levels are not used, except for patients with very high levels (>,170/100 mmHg or TC or TC/HDL >,8).

,

"So in the UK for example, GPs should be rewarded for treating people at high CVD risk, not those with raised individual risk factors."

,

RA: How can we better assist primary care practitioners in managing CVD and diabetes risk?

RJ: By providing user-friendly prediction tools that ideally are locally developed or validated, for assessing multifactorial CVD risk and by providing clear guidance and support to base treatment primarily on multifactorial risk not risk factors. So in the UK for example, GPs should be rewarded for treating people at high CVD risk, not those with raised individual risk factors.

RA: Could you please tell us more about heart age and cardiovascular risk?

RJ: Short-term (5- or 10-year) multifactorial CVD risk is the most clinically relevant measurement for deciding how a patient should be treated. This is because the magnitude of the benefits of treatment are directly proportional to the pre-treatment multifactorial risk and trials demonstrate that most of this benefit will accrue in about 5 years (note, this is one of the reasons we use a 5-year risk in New Zealand rather than a 10-year risk).

,

"...a 5- (or 10-year) multifactorial CVD risk percentage is not a measurement that is well understood by either patients or clinicians."

,

However, a 5- (or 10-year) multifactorial CVD risk percentage is not a measurement that is well understood by either patients or clinicians. By contrast, heart age is easy to understand and a patient’s heart age is calculated by first estimating their short-term multifactorial CVD risk, then determining the age at which that same patient would reach this risk level if they had the ideal risk factor profile. So a 35 year-old male smoker with a BP of 140 / 90 and a TC / HDL ratio might have a 5-year multifactorial CVD risk of about 5%, but if he was a non smoker with a BP of 120 / 75 and a TC / HDL ratio of four, he would reach a 5-year risk of 5% until he was about 55 years. So this 35 year old has a heart age of 55 years, 20 years older than his chronological age. This is a measurement that both patients and clinicians immediately understand and it is also closely linked to the patient’s 5- or 10-year multifactorial CVD risk, which should still be the key determinant of treatment decisions.

RA: What really needs to change to make people more aware and indeed act on their cardiovascular risk factors?

RJ: Changes are needed at two levels:

• At the population level, we need more taxation and regulations that make it easier for people to make healthier choices – e.g. making healthier food choices cheaper, making unhealthier choices like sugar-sweetened soft drinks unavailable in schools / hospitals, strengthening smoke-free policies, stating saturated fat / calorie content on fast-food menus etc...

"...we need more taxation and regulations that make it easier for people to make healthier choices – e.g. making healthier food choices cheaper..."

• At the individual level, we should provide patients with easy access to risk prediction tools like ‘heart age’ calculators. We have an on-line one that we developed with our National Heart Foundation (http://www.knowyournumbers.co.nz/heart-age-forecast.aspx).

Figure 1: Know your numbers heart-age calculator showing heart age and risk of cardiovascular event in next 5 years.

RA: What can pharma do to raise awareness of cardiovascular risk factors?

RJ: They can focus their clinical education on multifactorial risk rather than on individual risk factors. In addition, they can provide multifactorial risk assessment tools and concentrate on developing drug combinations (polypills) for simultaneously treating multiple risk factors.

,

"...CVD is increasingly becoming the most common disease of low and middle income countries.."

,

RA: What do you think the future of cardiovascular health looks like?

RJ: With the major reductions in CVD mortality in high income countries over the last 40 years, CVD will increasingly be a disease of the old and very old in these countries.

Younger people who have CVD events will live for many years after a CVD event and CVD is increasingly becoming the most common disease of low and middle income countries.

RA: Professor Jackson, thank you for your time today.

About the interviewee:

Rod Jackson is a professor of epidemiology at the University of Auckland. He is medically trained and has a PhD in Epidemiology.

He teaches public health and clinical epidemiology to undergraduate and postgraduate students and health professionals. He has led the development of the ‘Graphic Approach To Epidemiology’ (GATE) which he and his colleagues use as the basis for courses in epidemiology and in evidence-based practice / critical appraisal (www.epiq.co.nz).

His main research interest is the epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases. He is one of the architects of New Zealand risk-based clinical guidelines for managing CVD risk. His current research is based on PREDICT - a web-based decision support system being used to help primary and secondary care practitioners systematically manage CVD and diabetes risk at the 'moment of care'. PREDICT simultaneously generates a CVD research cohort that currently includes over 200,000 people and is growing at 1-2,000 per month.

Have you assessed your heart age?