Healthcare systems aren’t making the most of biosimilars: pharma needs to support them

Biosimilars could save European and US healthcare systems billions - but more needs to be done to maximise their benefits, writes Richard Staines.

Biosimilars are becoming an ever-greater part of the European pharma market, and are finally penetrating the US. The US market's first entrant was Sandoz's Zarxio in 2015.

A recent report by IMS Health, Delivering on the Potential of Biosimilar Medicines, forecasts that the global biologic medicines market will exceed $390 billion by 2020, and will then represent 28% by value of the global pharma market.

Biosimilars – close copies of biologic medicines now off patent – are set to play a significant role.

Although they are more expensive to develop and manufacture than small molecule generics, biosimilars are frequently priced around a third cheaper than originator drugs, a discount which increases with greater competition.

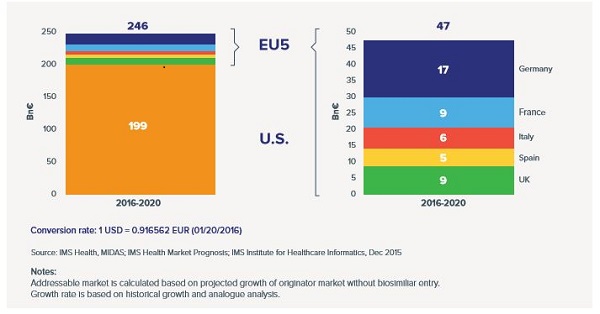

IMS says biosimilars can save the US and major EU markets up to $110 billion by 2020 – however there are serious doubts that these figures can be achieved without some major changes to the existing decision-making structures and incentives within healthcare systems.

But why, after all, should pharma companies support greater uptake of biosimilars? Didn't many of the companies which pioneered biologics try to block biosimilars entry to the market?

Well, yes, and originator companies are still vigorously defending their biologics with patents and any legal means.

But many big pharma companies are joining the biosimilars market themselves – very much a case of 'if you can't beat them, join them'.

Novartis has its off-patent drugs division Sandoz, which was the first to gain approval for Zarxio – used to treat anaemia related to cancer – via the new US FDA biosimilars pathway established under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. Similarly biosimilars specialist Hospira was acquired by Pfizer in 2015. Most remarkably, Amgen is gamekeeper turned poacher, and is set to market a biosimilar version of AbbVie's biologic blockbuster, Humira (adalimumab).

Moreover, biosimilars are now being accepted as an inevitable part of 21st Century healthcare, and pharma is being urged to back uptake – the argument being that savings created can allow spending on innovative new medicines.

"The prospect of more affordable biologic options that are safe and effective opens up opportunities for health systems to expand access to more patients, and frees up resources for investment in new areas," said Murray Aitken, IMS Health senior vice president and executive director of the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

Mr Aitken was making his remarks at the launch of the report, which outlines the challenges to healthcare systems in Europe and the US if they are to maximise the benefits of the new entrants.

IMS estimates that around 30 companies are actively developing biosimilar medicines for launch and are pursuing biosimilar versions of 16 distinct molecules that will lead to greater competition by 2020.

But Aitken warns: "Not all markets are ready to fully benefit from the imminent surge of biosimilar molecules," and there is clear variation across Europe in terms of uptake so far.

Europe

It is now 10 years since the arrival of the first biosimilar in Europe, Sandoz's human growth hormone (HGH) Omnitrope.

This is a version of somatropin, originally developed by Genentech/Pfizer under the brand name Genotropin.

These early biosimilars blazed a trail in the EU regulatory process, which is now well established – a total of 23 biosimilars are now approved in Europe.

t

EU5 + US sales of key biologics scheduled to lose patent protection 2015-2020

The addressable biosimilar medicines market in the EU5 and the US, 2016-2020

Figure sources: IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics

But uptake of these cheaper biologic copies remains less than streamlined in many European healthcare systems.

Germany has been one of the most successful countries in smoothing the path for biosimilars, providing education for doctors and introducing measures to stimulate biosimilar prescribing.

Its neighbour Austria has been much less successful, however. Biosimilars have price reductions imposed on them, penalties which threaten to limit access to some biosimilars.

But uptake of another inflammatory diseases biosimilar – Celltrion/Hospira's version of Johnson & Johnson/MSD's Remicade (infliximab) – has been slow on the NHS since its launch more than a year ago.

UK uptake

In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) is famously a keen user of small-molecule generic drugs, but it has been slow to realise savings from switching to biosimilars from branded biologics so far.

The number one therapy area for biosimilars is in the anti-TNF class and similar immunology and inflammation treatments. One of the key molecules is infliximab, based on Janssen's Remicade.

But uptake has been limited and concentrated within a minority of hospital trusts.

IMS Health data from December 2015 showed that 23% of infliximab usage in the UK was biosimilar, with just 24 trusts accounting for more than 50% of the uptake.

[caption id="attachment_25011" align="alignnone" width="350"] Celltrion's Remsima[/caption]

Celltrion's Remsima[/caption]

One company looking to gain greater market share is Napp Pharmaceuticals, which markets Remsima in the UK, one of several infliximab biosimilar brands. The drug was developed by Celltrion and gained EU approval in February 2015, and was subsequently licensed to Napp in the UK.

Andrew Roberts, director of market access at Napp Pharmaceuticals says its product is priced at a substantial discount to the list price of the originator.

Roberts told pharmaphorum: "There is a big opportunity for healthcare providers. Remsima was launched in March 2015 but it is only in the last three or four months that we are starting to see significant uptake."

He confirmed that frontline healthcare professionals aren't reporting any major differences in the clinical profile of biosimilars to the originator products, and that switching is now happening in UK hospitals.

Pricing varies across the country depending on rebates and discounts agreed by specific NHS organisations. One reason for the slow uptake has been a lack of prescribing guidance, which is finally being updated locally to encourage doctors to prescribe biosimilars.

Things are beginning to change now, thanks to a variety of new guidelines and initiatives. NICE guidance covering seven drugs in the class, including biosimilars, is already having an impact.

Meanwhile NHS England has prioritised their uptake in a work programme for its new Regional Medicines Optimisation Committees. These will look to eliminate any obstacles to greater biosimilar use, something which could save the cash-strapped NHS hundreds of millions of pounds over the next few years.

Roberts explained: "Clinicians are now clearer on where biosimiliars should be used; that's why we're beginning to see wider adoption."

The inertia has prompted the formation of the British Biosimilars Association (BBA) trade group, which aims to promote the cost-saving benefits and counter any resistance from branded drug manufacturers whose sales are threatened by biosimilars.

Napp aims to play a major role in the BBA as the organisation's work progresses.

Roberts suggested that, in the future, manufacturers may compete to provide "value-added services", as well as price, in order to get biosimilars included on drug tenders.

Humira not going down without a fight

Undoubtedly the largest scalp the biosimilars companies want to claim is AbbVie's inflammatory diseases drug Humira, (adalimumab), the biggest-selling drug in the world.

Outside the US, Humira sales are more than $1 billion per quarter, most of this revenue coming from Europe.

Humira's final European patents expire in 2018, and in 2017 in the US.

There are a dozen biosimilars under review by Europe's CHMP regulatory committee, including two versions of Humira.

The branded pharma companies are fighting hard should their products face biosimilar competition – such as AbbVie's attempts to protect Humira with a 'thicket of patents' in Europe.

Biogen has teamed up with Samsung to create the Samsung Bioepis joint venture, which has already launched Benepali early this year – a verison of Pfizer's Enbrel (etanercept) for inflammatory diseases.

Samsung Bioepis has launched a legal challenge against AbbVie's Humira patents in the UK, although it has not confirmed whether it has filed a biosimilar in the UK.

Meanwhile Amgen, the first to suffer from the launch of biosimilar versions of its originator products, has also filed its own copycat version of adalimumab. With the regulatory and marketing expertise of such biologics titans as Amgen, the market should start to grow more rapidly and regulators, healthcare systems and pharma should work together to make it happen.

That way, pharma has the best possible case for calling for the savings made to be directed for innovative new drugs which can help advance medical care.

Read the full report, Delivering on the Potential of Biosimilar Medicines, via the link on the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics home page.

About the author:

Richard Staines is Senior Reporter at pharmaphorum. He has been writing about health for more than 10 years. Contact him on Richard.Staines@pharmaphorum.com