Biotech in post-Brexit Britain: the future for the UK’s pharma-innovation engine?

Drug development can be quite a risky business at the best of times, but particularly in the biotech sector where companies may only have a few assets to their name.

But while negative headlines about the UK opportunity, mostly related to Brexit, may abound at the moment, those with an intimate knowledge of this vibrant sector are keen to point out that the UK is world-leading country in which to do business, and will in fact get better in coming years.

In a recent webinar conducted by IQVIA and pharmaphorum, several experts gathered to give their views on the current state of UK biotech and what the future might look like.

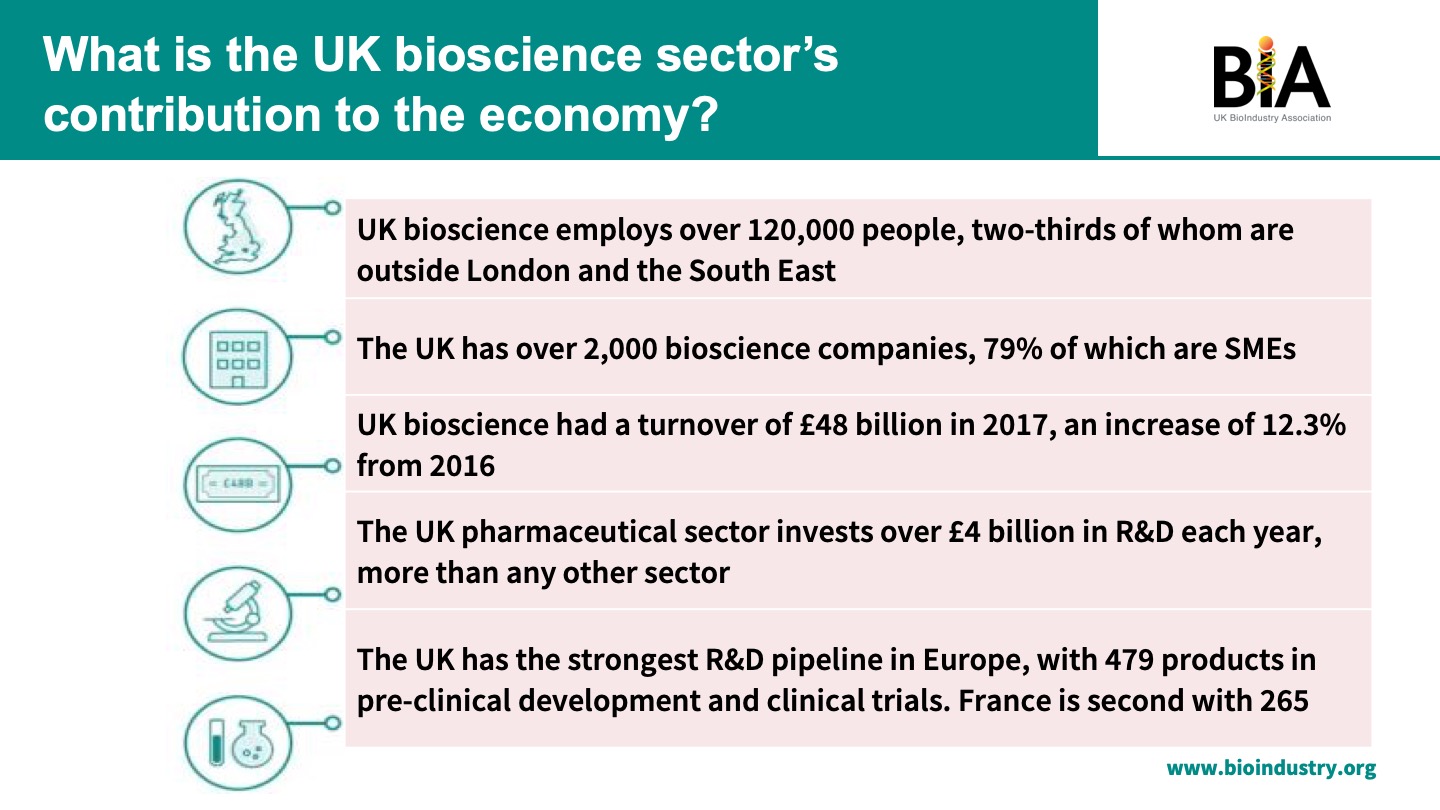

Steve Bates, CEO of the BioIndustry Association (BIA), was keen to elaborate on all the ways in which the sector provides a significant contribution to the UK and how the UK gives back to the industry.

“We provide jobs, a significant amount of growth in the economy, a significant amount of overseas investment back into the economy, as well as, most importantly, the vital products that are needed by patients with unmet medical needs,” he said.

And UK biotech companies see a great deal of success in return – investors ploughed £2.2 billion into the sector in 2018, surpassing the 2017 annual total of £1.2 billion.

Bates pointed out that despite Brexit uncertainty the Life Sciences Industrial Strategy and the first life sciences sector deal announced in 2017 (as well as the second life sciences sector deal announced in December 2018, editor’s note) exist to help guide the sector into an even brighter future with a more favourable fiscal, regulatory and reimbursement environment.

“It’s going well, and we’re linking the scientific underpinnings of the sector with thinking across the healthcare system and the government to try and improve the UK’s position on this. It means we’ve got input into fiscal discussion with the treasury, regulatory discussion with the MHRA and discussion with the NHS about the research, digital and collaborative environment.”

“The UK is still an important proving ground for new assets,” added Dean Summerfield, senior vice president, RWAS and commercial technology tolutions, NEMEA at IQVIA. “Because of the reputation and openness of organisations like NICE, the NHS, it’s a great place to refine your value proposition through active dialogue. If you build it right and you get it right here you will likely have the wherewithal to take it anywhere in the world."

Dean Summerfield, IQVIA

Sheela Upadhyaya, associate director of highly specialised technologies at NICE, agreed, adding: “This environment enables full understanding of stakeholder views and creation of a collaborative, pragmatic strategy. Our mechanisms and honest dialogue around capabilities are envied in other countries.”

Fred Jacobs, CEO of biotech TYG Oncology, was also keen to point out the attractiveness of the UK to companies like his own.

TYG’s leadership team consists of people from all around the world, but Jacobs said they chose to come to the UK because it is a great environment to conduct research and drug development.

He added that the NHS is one of the areas where the UK could have a global advantage over other countries.

“Historically the UK has been one of the last countries to adopt new technologies and we should be in the lead. We have the infrastructure in place, we have a unique health data ecosystem including electronic patient records such that we should be able to identify patient cohorts faster than anywhere else in the world and match them up with prospective drugs better than other countries.

Fred Jacobs, TYG

“We also need to think about the future UK regulatory system being unique and distinct. It may not be the EMA or the FDA, but it could be something in between, and it could be faster. It could be the place that people want to go to develop their drugs and test their drugs first instead of the place where they go and implement them last.”

Jacobs added that developing an infrastructure that supports the biotech industry would accelerate the UK even further.

“If the UK is going to become a global centre of excellence we need to have the ability to go from raw materials right through to finished products, and right now the emphasis of the country’s skillset is more on developing lower-value raw materials as opposed to higher-value fill/finish products, most of which are presently manufactured in China. We need to go from making raw materials to finished products; that will increase the value of the entire ecosystem.”

Challenges for commercialisation

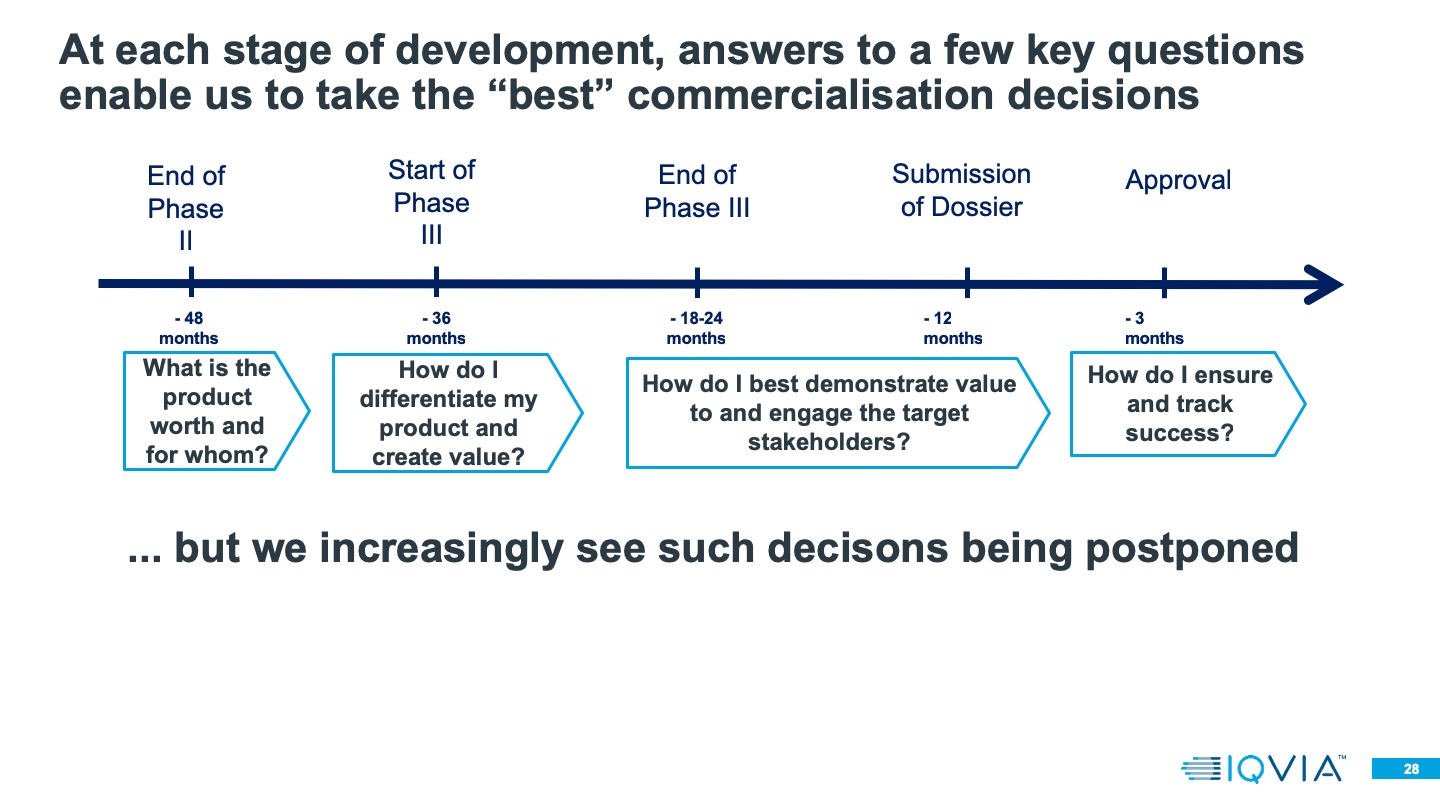

While companies can be very successful when commerciallsing in the UK, Summerfield noted that it’s important they consider how different parts of the system define value.

Value is defined quite differently depending on who in the complex system you’re talking to,” he said. “When we’re thinking about commercialisation decisions that run alongside clinical development plans, we have to think about how we engage in a dialogue with these different players to understand what they need – not generically, but for the particular product device that we’re developing.”

He stressed the importance of clearly articulating evidence, especially for highly specialised technologies (HST), when approaching payers.

“Way back when we’re doing Phase II/Phase II Bs, ambiguity in who the product is for, what value it can provide, where we target in the system, can all lead to a lot of wasted expenditure and a lot of deliberation because we don't have agreement on the target product profile, we don’t know who the patient group is.”

Luckily, key players in the UK system are usually willing to engage in a productive dialogue.

For instance, one area that has historically faced several challenges relating to access is HSTs – but NICE and the NHS have started taking steps to address these issues.

NICE’s Upadhyaya points out that challenges in HSTs include a lack of sufficient clinical data, no established standard of care, insufficient knowledge of the natural history of the disease together with short duration of studies and follow-up studies. This results in uncertainties for healthcare payers and challenges in creating equity of access to drugs.

In response, NICE has introduced the ‘managed access agreement’ for HST programmes. These are risk-sharing agreements comprising of commercial arrangements with NHS England that allow companies to collect real-world evidence about a drug while it is available on the health service.

“We’re acknowledging that there are a huge number of uncertainties in this space,” Upadhyaya said, “but without access to these drugs we may never know the answers and patients may suffer for longer.”

In a managed access agreement, the product in question becomes available on the NHS for a limited time (usually three to five years), during which the company commits to collecting additional real-world data to fill the uncertainty gap.

“At the end of that agreement NICE as a body will re-evaluate the technology to see if it is efficacious,” Upadhyaya said. “And we’ve had quite a lot of success in putting those together.”

It seems that the future is bright for biotech in the UK, with stakeholders across the industry and the healthcare system keen to work together to see its growth and success continue. With a few changes at governmental and industry level the UK could soon lead the field as the number one research destination in Europe for novel drug testing.

IQVIA and pharmaphorum’s recent webinar, Realising the biotech promise: addressing the path to market can be viewed here.