Digital health literacy: the bright tail of the comet

We have just entered 2020, a year that marks the point of arrival of many global and national agendas of research and innovation programmes. Among reviews of the past decade and new predictions for 2025, one thing is clear: digital transformation in healthcare is gathering pace and will continue its rapid and unstoppable course, settling in some countries as an accessible opportunity.

The approval of regulatory paths for digital health, which have spread from the US to Europe in France, UK and Germany, are expected to increase the number of patients and physicians experiencing the availability of new approaches and options in their care pathways. One of the major challenges of the upcoming years will therefore be to enhance the awareness and understanding of digital health (that is, boost digital health literacy) among the various stakeholders, thus creating the conditions for proper adoption.

As in other fields of innovation, the adoption process in the digital healthcare space appears to follow a ‘pulled’ rather than a ‘pushed’ route, driven by technology that rapidly generates applications and need-driven interactions.

Like a comet, the digital health revolution is whizzing through our time, with its iced core of technology igniting and starting to shine, and progressively shedding light and matter behind itself once it enters the orbit of the ‘healthcare solar system’. And, while scientists and experts have the capabilities and tools to spot the core, understand its nature and predict its trajectory, the majority will be able to recognise the comet as such only because of its long and brilliant tail. Within this comet, digital health literacy finds its place in the particles of that tail, in that bright reflection that makes digital health visible, comprehensible and accessible.

Transformation and digital health literacy

Moving away from that metaphor, it remains evident that the degree of digital health literacy – of physicians first and foremost, but also of patients, institutions and payers – can really make the difference between an efficient integration and a missed opportunity.

Digital health literacy must therefore be considered in all respects a primary determinant in the digital transformation of healthcare.

This seems to be an achievable goal, given that digital solutions allow for the delivery of multi-media information, at different reading levels, in multiple languages, and using formal and informal channels and methods.

However, as digital health literacy is an extension of health literacy, it suffers from similar limits and contradictions, and the global scenario of access to contemporary health information is patchy.

On the one hand, people (including physicians) are already very active in searching for information and solutions in the health space, and overall there is an enormous amount of health-related data traffic.

According to recent WHO data, 80% of health-related consultations are carried out on Google or other search engines, and one in 20 searches on Google relates to health. In the US, 72% of adults active on the internet search for information about their health (60% in Europe).

Active users, however, are often overwhelmed by an information overload: today Google searches return more than two billion results for "cancer" and almost 600 million for "diabetes" (note that these results were, respectively, 575 million and 250 million in 2017).

On the other hand, the WHO reported that 53% of the world's population is offline (0-25% in the US and most of Europe, 26-50% in some European countries). So, there is the risk that the most vulnerable people are left behind in the transition and that existing health inequalities experienced by people who have lower levels of digital health literacy can be exacerbated.

Digital health literacy today

Given this picture, how is the digital health literacy aim being pursued today, and who are the players in this field?

Globally, WHO is increasingly paying attention to digital health literacy, currently defined as “the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem”.

According to this definition, digital health literacy seems to solely relate to the use of digital tools to access overall health information. It does not cover the important aspect of being literate about digital health (not a trivial difference).

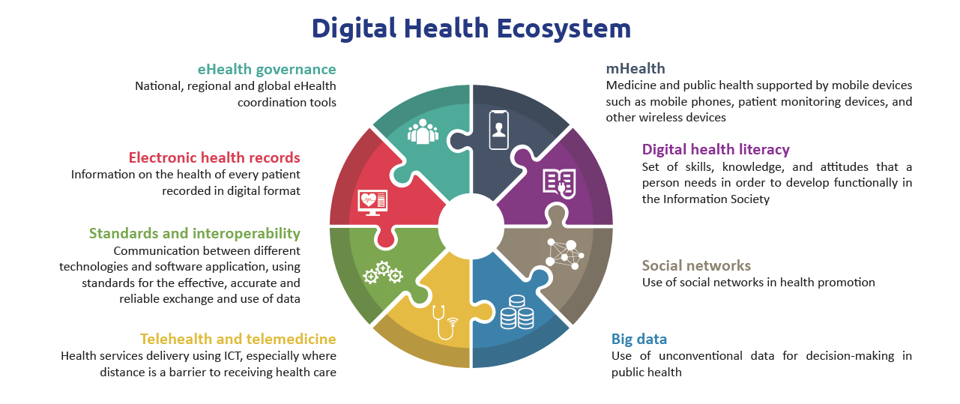

In its original meaning, WHO included digital health literacy among the components of the Digital Health Ecosystem, as well as digital health, telemedicine, big data and governance interventions. In the last two years, it has published relevant documents, including Digital Technologies: Shaping the Future of Primary Health Care (2018) and the first WHO Guideline Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening (2019).

Source: WHO

Another global player in this area is UNICEF, which has published the documents UNICEF’s Approach to Digital Health and Health Literacy for People-Centred Care: Where do OECD Countries Stand?

In Europe “improving digital health literacy must be central to all European efforts on enabling the digital transformation of health care, as well as to health promotion efforts to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, said EuroHealthNet director Caroline Costongs.

Best cases reported for promoting digital health literacy in European countries include:

- The multichannel SNS24 health platform in Portugal

- The DIGI-UNG, an online platform that offers integrated services including health for teenagers in Norway

- The 4 Steps to eHealth4All model in the Netherlands

Communications approaches to foster health literacy

Pharmaceutical companies also increasingly understand the value of promoting health literacy and reducing the barriers between HCPs and patients. As an example, at the European Respiratory Society Congress 2019, Menarini started engaging specialty physicians with a noteworthy Smash the Glass campaign, aimed at fostering health literacy and active listening of patients.

Players active in the field of communications’ strategy and consultancy – such as Intouch Solutions in the US and Healthware International in Europe – have a significant role not only in producing and divulgating comprehensible information, but also developing solutions and easy to use digital tools to support the daily practice of clinicians.

Moreover, dedicated conferences such as Frontiers Health have evolved from an innovation showcase to an active platform enabling start-ups, pharmaceutical companies and investors to connect. All these initiatives, taken together, have the significant consequence to advance in parallel both digital health solutions and digital health literacy.

In conclusion, fostering digital health literacy is a necessary and urgent ingredient of digital health integration and cannot be postponed, as it is key that knowledge and skills parallel technology advances. Physicians who are digitally health literate can accelerate the adoption and realise the potential of digital health in their territory, contributing to the observance of healthy behaviours, enhanced wellbeing and improved prevention models. Likewise, people with a sufficient level of digital health literacy can be more active in achieving their health potential.

As with other health advances, there is the risk that those with the highest need will benefit least; however, having an increasing number of users integrating traditional and digital health interventions will progressively facilitate the resolution of problems related to the complexity of management, triggering and nurturing a virtuous circle beneficial to all. In perspective, such an approach is then expected to reduce, rather than widen, health inequalities.

As a further next step, it might be appropriate to reconsider and revise the existing definition of digital health literacy to better grasp the latitude of the concept, namely extending from the current “Digital [Health Literacy]” to a more comprehensive and prospective meaning of “[Digital Health] Literacy”.

About the author

Elisabetta Ravot is head of science at Healthware International. Holding a PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology, she began her career as a research scientist in international academic centres, including the prestigious ZMBH in Heidelberg and the Research Institute for Human Gene Therapy in Pavia. In 2000, she transitioned from doing science to communicating it, entering the space of healthcare agencies. Since then, she has collaborated with several major international communication groups, experiencing first-hand the profound transformation of this sector. In her current role, she provides consultancy and guidance to projects that integrate scientific expertise, communication strategies, and digital technologies, with a strong focus on digital health. She’s also part of national boards aimed at enabling the development and adoption of digital therapies.

Elisabetta Ravot is head of science at Healthware International. Holding a PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology, she began her career as a research scientist in international academic centres, including the prestigious ZMBH in Heidelberg and the Research Institute for Human Gene Therapy in Pavia. In 2000, she transitioned from doing science to communicating it, entering the space of healthcare agencies. Since then, she has collaborated with several major international communication groups, experiencing first-hand the profound transformation of this sector. In her current role, she provides consultancy and guidance to projects that integrate scientific expertise, communication strategies, and digital technologies, with a strong focus on digital health. She’s also part of national boards aimed at enabling the development and adoption of digital therapies.

References

EurohealthNet. 2019. Digital health literacy: how new skills can help improve health, equity, and sustainability, 2019. https://eurohealthnet.eu/publication/digital-health-literacy-how-new-skills-can-help-improve-health-equity-and-sustainability

EurohealthNet. 2019. Addressing digital health literacy is essential to avoid widening health inequality. https://eurohealthnet.eu/publication/addressing-digital-health-literacy-is-essential-to-avoid-widening-health-inequalities-eurohealthnet-expert-workshop-2019/

Novillo Ortiz D (WHO) 2017. Digital health literacy. who.int/global-coordination-mechanism/working-groups/digital_hl.pdf

Roland Berger Focus. October 2019. Future of health - An industry goes digital – faster than expected. https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Media/IT/?country=IT#/pressreleases/europes-digital-healthcare-market-forecast-to-grow-to-eur-155-billion-by-2025-2934425