Is the UK an attractive launch market?

Leela Barham tries to cut through the lobbying to identify objective measures of the attractiveness of the UK market for launching new medicines.

Lobbying

The UK is currently amid negotiations on a new voluntary scheme, due to start in 2024, that sets out the framework for pricing and access to branded treatments. If it can be agreed, this will be a successor to the current scheme, known as VPAS.

The current VPAS, which began in 2019 and will end on 31st December 2023, is predicted to result in £7 billion in rebates from companies to the government.

With so much money on the table, there’s a lot of interest in what a new scheme will look like and how favourable it will be to industry or the government. That means – understandably – lobbying has stepped up.

Differences of opinion on the attractiveness of the UK as a launch market

One of the key issues that has emerged from lobbying is a concern that the UK has become less attractive for launching new treatments with VPAS in place. It follows that would continue should a successor keep the same approach.

For example, Scott Cooke, general manager of Bristol Myers Squibb, UK & Ireland, has said: “The UK is operating in a highly competitive international landscape for investment in life sciences. As a result of this clawback, our global HQ is seeing the UK as a less attractive place to invest in science and innovation and to launch new medicines. Faltering competitiveness undermines a great opportunity in the UK, which has a strong heritage in life sciences, leading universities, and a pool of nationwide talent.”

The opposite view is also held. Academics from the London School of Economics (LSE), the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), and the University of York have suggested that “it would be unlikely and costly for pharmaceutical companies to forego a UK launch of their products, since the NHS has long been a reliable market for them.”

Objective measures?

Given that there is a difference of opinion on just how attractive the UK is as a launch market, is there data that can shed light? The answer is yes, in part - at least at the time that past decisions were taken.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) tracks the number of new product launches as one of its operational metrics for the VPAS. Their most recent set of metrics, as of September 2022, noted that there had been a slight decrease in the number of new product launches in Q1-Q2 of 2022 versus the previous year (56 versus 54). The trouble with that is that it shows what has come to the UK, not what hasn’t. That’s what we really need to know; although, the number of product launches is a useful insight, nevertheless.

Another source of data is to look at non-submissions, also known as terminated appraisals, at the HTA agency, NICE. That’s the argument that David Watson has put forward in response to a BMJ editorial that preceded but used many of the same arguments, as the LSE et al report. Watson wrote, “The number of terminated NICE appraisals has rapidly increased, with just over a quarter of NICE’s work programme terminated in 2022/23.”

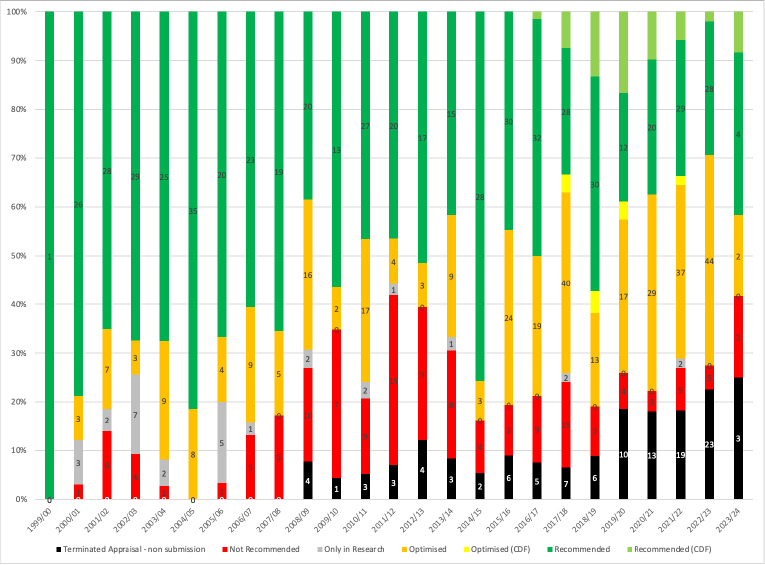

Watson is (roughly) right; 23 of 102 Technology Appraisals resulted in a terminated appraisal, or 23%. For 2023/24, so far it is 25% (3 out of 12 TAs). And it is an issue that is not going away (Figure 1).

Figure 1: NICE Technology Appraisal Recommendations, 1999/00 to 2023/24*

Source: Analysis of NICE data. * Up to NICE TA890, published in May 2023.

The issue of non-submissions has also cropped up in a House of Lords debate, held on 25th May, that sought to influence the ongoing VPAS negotiations.

Lord Lansley, former Secretary of State for Health, said: “If we save a bit on NHS purchasing and parade to the rest of the world that we have the lowest medicine prices, the inevitable result - which we have seen - is a doubling of the number of pharmaceutical companies withdrawing their products from NICE evaluations. That is not a place where we want to be. We want those evaluations to take place.”

The LSE et al report doesn’t mention non-submissions at all.

Important nuances

The LSE et al report points to a three-year exemption for companies who bring new active substances (NAS) to the UK market in paying the VPAS rebate on those sales. That is part of the argument made that the UK remains attractive for launch.

As ever, though, there is nuance here. VPAS members still pay for those sales. The company that sells the NAS may also find they get few sales within those three years; IQVIA analysis of treatments given NICE approval suggests it can take four years to get uptake. A benefit on paper may well not be one in the market. That’s another way to use data to help unpick inherently subjective sentiments.

The future

The ongoing lobbying is geared at trying to shape a successor deal for VPAS that hasn’t yet been agreed. That’s the problem: the industry is bound to say times are tough in the UK (and honestly, I think that they are) and the government is bound to say that they aren’t as bad as all that (and they are probably a little bit right, too).

What may be the most practical step to take is to codify the measures that need to be tracked and discussed by both sides and used in the future to determine the success of how the UK manages pricing and access for new treatments, be that through a continuation of a VPAS style agreement, a different style of voluntary altogether, or even via the statutory alternative that would bite should no agreement on a voluntary scheme be reached. Non-submissions are not part of the metrics looked at, but perhaps they should be. Even better if there is an agreement to identify and track the missing launches.