Finding a long-term fix to UK’s growing patient waiting list

The pandemic severely hindered the UK’s ability to treat patients in need. Ben Hargreaves learns how the impact of treatment delays is still being felt, and the urgent action that is being taken to address an NHS waiting list that has grown to record proportions.

The number of people on NHS waiting lists is currently at record highs. According to data published by the British Medical Association, there are 7.5 million individuals waiting for treatment in England. Approximately 3 million of these patients have been waiting for over 18 weeks, and close to 400,000 have been waiting over a year.

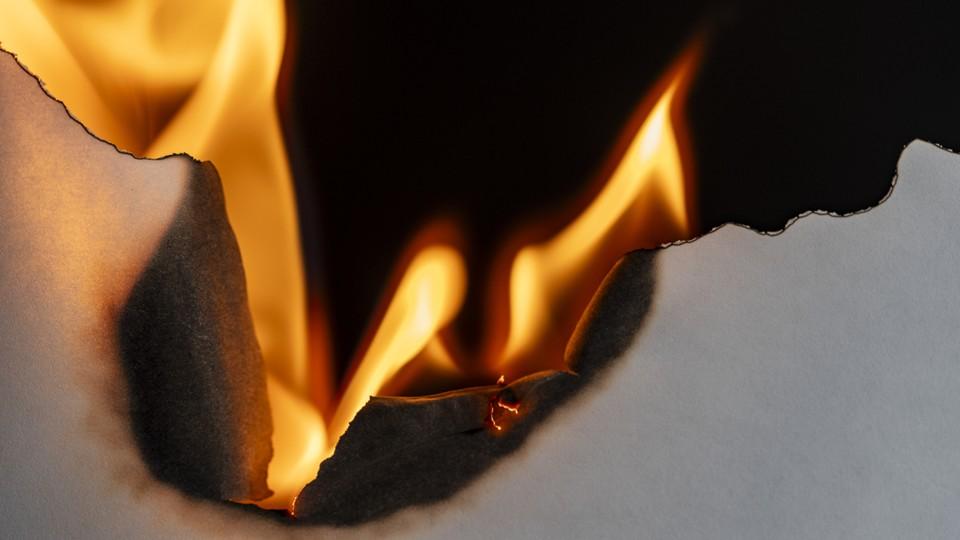

Despite recently reaching unprecedented levels, the issue of a growing waiting list is not a new problem for the UK’s health service. Since 2010, the waiting list has been steadily growing to current levels. The pandemic, however, lit the fuse for the numbers on the waiting list to explode, as many treatments were delayed and patients stayed away from hospitals at the peak of the crisis.

A healthcare system in crisis

There are a number of issues that are playing a part in the continued growth of the waiting list and delays on receiving treatment, but there is no doubt that the pandemic played a major part in this. During the first wave of the pandemic, there was an approximate 30% fall in appointments in general practice, suggests Nuffield Trust. The level of appointments after this period resumed at similar levels to pre-pandemic, but individuals experiencing health issues were more likely to have more serious complaints by the time they visited their GP. In addition, the number of referrals for a first outpatient appointment from GPs also fell to lower levels than pre-pandemic. This latter fact has been associated with lower capacity in hospitals and patients not coming forwards for care, as well as broader efforts to reduce unnecessary referrals.

However, the temporary issues highlighted by the pandemic are more widely indicative of larger, systemic challenges facing the healthcare system. Amit Aggarwal, executive director of Medical Affairs & Strategic Partnerships with The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), told pharmaphorum of one significant driver: “The NHS is facing increasing demand driven partly by an ageing population with increasingly complex health needs.”

Another major issue facing the NHS is the recruitment challenge the service faces. The King’s Fund, an independent charity focused on healthcare, conducted research into the recruitment situation and concluded that “a prolonged funding squeeze between 2008 and 2018, combined with years of poor workforce planning, weak policy, and fragmented responsibilities, means that staff shortages have become endemic.”

The research did show that additional funding provided in recent years had a positive effect, but there are still areas of major concern. One example provided is that the number of general practitioners in permanent roles has fallen by 6.6% between 2016 and 2021.

Public issue, private solution?

The long waiting times for patients to receive diagnosis and treatment means that there is an urgent search for solutions. The NHS has previously stated that it anticipates the waiting list numbers to start reducing by around March 2024. However, the reality of an ageing population and the financial challenges hindering the service mean that both the UK government and private equity foresee continued difficulties in providing adequate care for the country with the current model.

As part of an initiative to open a greater number of community diagnostic centres (CDCs), the UK government announced in August that it would open 13 new CDCs in an attempt to reduce the NHS waiting list. The centres will provide testing capacity of close to 750,000 tests per year once completed, easing some of the burden placed on hospitals. Of note, however, is that eight of these CDCs will be run privately, with specialist providers running the testing and also owning the buildings. This move arrives as the government leans on private sector capacity to try to provide a solution to the NHS waiting list. NHS England national clinical director for elective care, Stella Vig, stated that use of the independent sector had increased by more than a third since April 2021.

In recent years, private equity has emerged as a larger player in the UK healthcare industry, as PE firms make strategic investments with a long-term view on the demands being placed on the NHS. The Financial Times recently highlighted the surge in PE firms snapping up UK healthcare companies, with 150 such deals recorded since 2021. During 2023, there have already been 25 deals agreed, which its authors noted go against the broader grain of a slowdown in M&A in the PE sector. According to PitchBook, the overall value of PE investment into UK healthcare has grown consistently over the last decade – in 2013, PE firms made £3.1 billion of investment, which subsequently rose to £15.4 billion in 2022.

The authors of the analysis reach the conclusion that the motivation for these investments is “to capitalise on addressing NHS inefficiencies and backlogs that have grown over the years,” and this process has been accelerated by the impact of the pandemic. However, they also note one of the major contentions to this growing private ownership of services to the NHS, which is public sentiment towards the service, regarded as a ‘national treasure,’ and general scepticism towards privatisation. The authors note: “Any upside that comes with plugging gaps in the system will be tempered by a degree of reputational risk.”

What role for the pharma industry?

For the pharmaceutical industry’s part, its role could be seen as being limited to the treatment of existing illnesses. However, Aggarwal explained that the industry’s role can go further, stating: “One area to focus on is prevention, and how the uptake of vaccines and other preventative medicines can improve wider public health. Another is through partnerships with the NHS to improve treatment pathways and the uptake of new therapies to ensure patients get the right treatments as soon as possible.”

In terms of what these greater partnership pathways could provide, Brian Duggan, partnerships director at the ABPI, has previously outlined the importance of creative partnership between industry, the NHS, and local communities. Duggan reference MSD’s campaign on lung cancer awareness that helped to support lung cancer referrals during the pandemic, which resulted in a 5.4% increase in referrals.

In terms of addressing the waiting list issues, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Boehringer Ingelheim joined forces to establish a clinic for people with cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Duggan explained that this initiative helped reduce waiting lists for diabetes review, subsequently reducing patient visits in primary and secondary care settings. The outcomes resulted in 38% of patients being provided with a home blood pressure monitor, and 65% being given smoking cessation advice and therapy.

The various angles of attack on the NHS waiting list show that there is no one solution to improving the speed at which patients are seen and receive necessary treatment. The alternatives mentioned to the existing model are also just a few of a number of proposed means of providing a more effective healthcare system. There are discussions on a number of other potential solutions, such as virtual wards, and emergency plans for patients to travel for treatment, which just highlights both the gravity of the situation and readiness to embrace methods that could provide an immediate relief.

What is clear is that the UK government is accepting the role of privately-run services as a key part of the NHS infrastructure, due to the severity of the challenges faced in reducing the patient waiting list. With PE investments only increasing, this is likely a facet of the service that will only grow moving into the future, and the pandemic could be the marker point of when this process accelerated.