UK gets guidance on synthetic human embryos for research

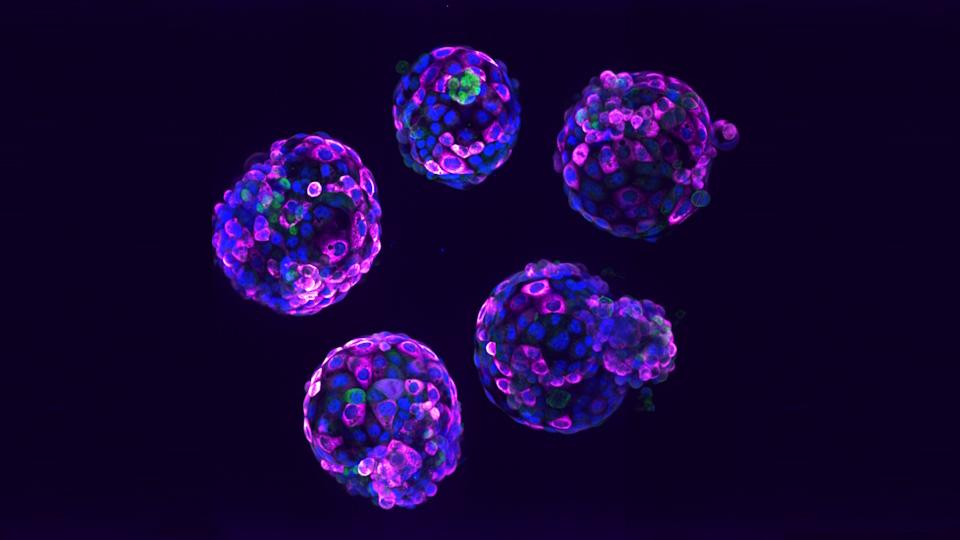

Human stem cell-based embryo model – Blastoids. Blue marks all nuclei, the green label marks cells of the inner cell mass, and the pink label is a readout of a ribosomal protein

A new code of practice has been drawn up in the UK to try to make sure that research on human embryo models derived from stem cells is carried out ethically and responsibly.

Stem cell-based embryo models, or SCBEMs, are three-dimensional biological structures that can mimic some aspects of early human embryo development and have been used by scientists over many years for a range of research purposes.

Those include investigating the causes of pregnancy loss, improving in vitro fertilisation (IVF), gaining insights into congenital diseases, testing drugs to see if they may harm an embryo in the womb, and drug discovery.

Last year, SCBEMs were thrust into the spotlight after scientists created a model with a heartbeat and blood cells, similar to what might be seen in the first month after conception, and another with structures that would be seen in natural embryos at around 14 days of development.

They have no formal definition or regulation in UK law, so the code of practice – developed by a working group of experts from a range of institutions across the country – sets out a framework that could remove uncertainty for scientists working in an ethical grey area.

Strict limits on the use of human embryos in research means that the SCBEMs can provide “insights into critical stages of early human development that are normally inaccessible to researchers,” according to the group, which is led by the University of Cambridge and the Progress Educational Trust.

At the heart of the code is the creation of a dedicated Oversight Committee that will review each proposed research project involving SCBEMs.

It also recognises that there must be a limit to how long embryo models can be grown in the lab and, as this may vary depending on the model, asks researchers to provide “clear justification” of the length of their studies on a case-by-case basis.

The document also prohibits any human SCBEM from being transferred into the womb of a human, or animal, or being allowed to develop into a viable organism in the lab.

“Embryo models have huge potential and we want to realise this, while also limiting the risks,” commented Professor Kathy Niakan of Cambridge University, who is a member of the working group.

The code “will allow stem cell-based embryo models to be grown in the lab long enough to gain meaningful biological understanding, but […] asks researchers to fully justify what they’re doing in scientific and ethical terms,” she added.

The UK move follows the publication of guidelines published by the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) in 2021, which also cover SCBEMs, but according to Professor Robin Lovell-Badge of the Francis Crick Institute “mesh better with the UK’s way of governing research on human embryology.”

He noted that SCBEMs will never completely replace the need for using some normal human embryos in research, but, because they can be produced in large numbers, will allow “types of research that could not be conducted on embryos, such as screens for biologically important drugs or genes.”

Peter Thompson, chief executive of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which regulates human embryo research in the UK, noted that UK law currently does not allow embryo models to be used in patient treatment.

“Last year, we put forward proposals for law reform, which include ‘future proofing’ it, so that it is better able to accommodate future scientific developments and new technologies, such as these,” he said.

“In the meantime, this new voluntary code will help researchers who have been uncertain about where they stand legally and ethically.”