Avacta hoping to disrupt antibody drug dominance

Monoclonal antibodies are now a mainstay of the pharma industry, and therapies using the technology now account for around $85 billion in annual sales.

But despite their prevalence, there are drawbacks - they are difficult to create and manufacture and must be stored in a controlled environment to ensure they remain effective.

Now numerous companies are looking at ways to improve on the monoclonal antibody (mAb) and its famous “Y” configuration.

UK-based biotech Avacta is one of such company, and aims to develop cheaper biologics which avoid many of these problems.

The company's chief executive Alastair Smith set out the company's strategy in an interview with pharmaphorum, saying its 'Affimers' technology can be a commercial success as diagnostics and also as therapeutic molecules.

“Right across the piece, we think there are opportunities,” said Smith.

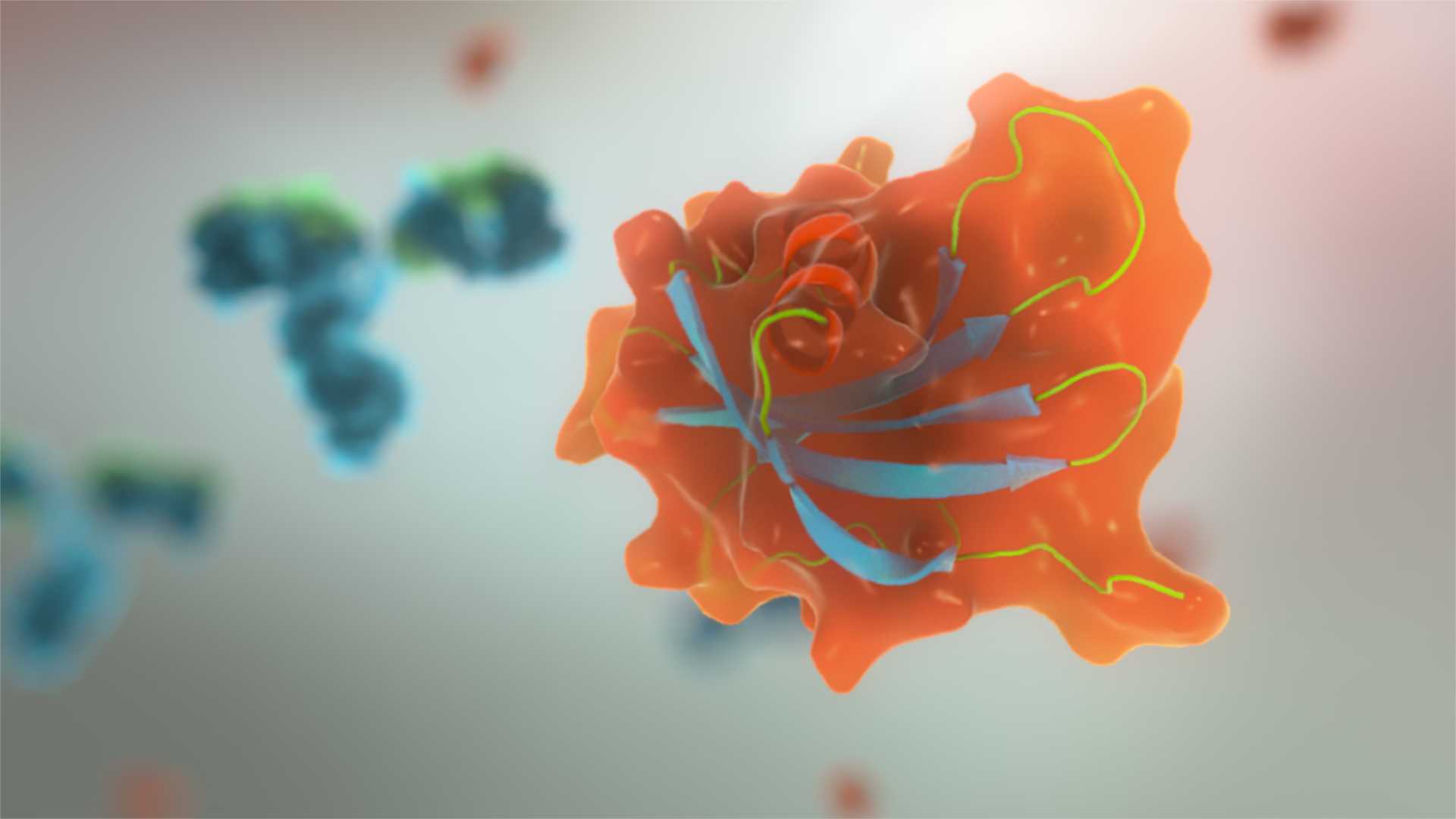

Affimers (pictured) are small single domain proteins with a specific binding site attached. They can also be strung together to make bispecific proteins that are more flexible than antibodies. Avacta reckons that it can string Affimers together that could bind to up to five different targets at once.

Currently in clinical development, the company aims to get the technology into the clinic later this decade.

Affimers bind to targets in the same way as antibodies, but don't have to be derived from animal cells, and can instead be manufactured much more simply in vitro.

One such next-generation technology are bispecific antibodies, which bind to two different sites on the same or different molecules, rather than just one.

A bispecific antibody has been approved – Amgen's Blincyto (blinatumomab) for leukaemia – but biotech Avacta insists that it has a new technology that can provide the specific binding properties of antibodies, without the need to produce such a large molecule. Its technology also allows for easier creation of bispecific drugs, or drugs that bind to three or more sites at once.

But Alastair Smith says that even bispecific antibodies retain some of the problems of traditional troublesome to produce. “When you try and do that with antibodies they become very difficult to manufacture,” he says.

The company aims to kick-start its business by producing Affimers used in diagnostic tests – a much easier market to enter than therapeutics.

Avacta then plans to progress into the more lucrative therapeutics market, using revenues generated by its diagnostics business.

In the meantime, Avacta continues to develop Affimers that bind to targets as diverse as the Zika virus, PD-L1 commonly targeted in cancer immunotherapy, and somewhat bizarrely, the explosive TNT.

“We hope to have an (investigational new drug) filing in place in 2018 and first in human trials in 2019.”

Smith says Affimers could also be fixed to the surface of T-cells to create cancer immunotherapies similar to therapies currently under development. They could also be turned into a conjugate that delivers a lethal payload to destroy targeted cells or proteins.

But Avacta is not alone in its quest to produce alternatives to mAbs. Ablynx is developing an IL-6 rheumatoid arthritis inhibitor, vobarilizumab, which AbbVie could choose to take into late-stage trials.

Ablynx bases its drugs around “nanobodies” – smaller antibodies that are derived from the immune systems of camels and llamas.

Molecular Partners is developing drugs based on DARPins, genetically engineered antibody mimetic proteins based on naturally-occurring ankyrin proteins.

And Pieris Pharmaceuticals is developing drugs based around Anticalins – derived from lipocalins, which are low molecular weight human proteins found in blood plasma and other body fluids.

The competition looks tough, but Smith is convinced that Avcacta's strategy of producing less risky diagnostics first before moving to therapeutics will pay dividends in the long run.

Brokers finnCap agree, noting that the AIM-listed company, valued at around £60m, could be worth much more if it achieves its long-term goal using Affimers to develop therapeutic drugs.