Do better: The message to the industry from an analysis of clinical evidence submitted to NICE over 20 years

Dr Leeza Osipenko and colleagues analysed the quality of clinical evidence submitted by companies to NICE technology appraisals (TAs) over the last 20 years. The take-home message is that the industry needs to do better in generating evidence to support NICE appraisals in the future.

But is it a realistic ask?

Consistently poor-quality clinical evidence

“The primary components of clinical evidence influencing NICE’s decision framework were of poor quality.” That’s the conclusion reached after Dr Osipenko and colleagues reviewed 409 NICE TAs, published between 2000 to 2019. 384 of these TAs were on drugs.

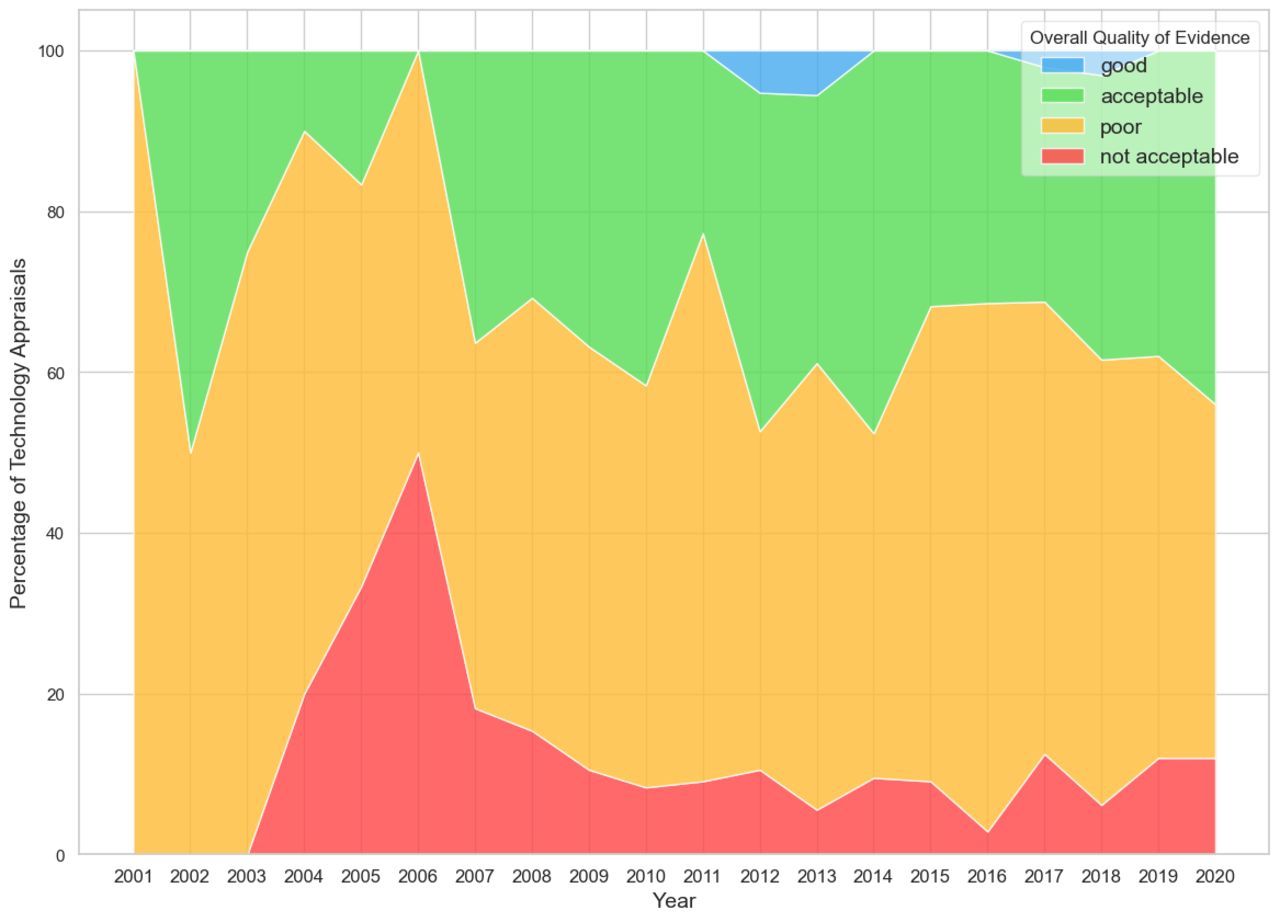

Their analysis is presented using colour coding and it’s evident that there were consistently very few appraisals that the team thought had ‘good’ overall quality of evidence (blue in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overall quality of evidence submitted to the appraisal committee

Osipenko et al. BMJ Open 2024;14:e074341

Dr Osipenko is CEO of the non-profit Consilium Scientific, as well as a senior visiting fellow at the London School of Economics, and previously held positions at NICE.

Slower and poorer decisions result

The authors point to two significant problems that result from low-quality submissions from companies.

First, drawing upon work by others, Osipenko and others argue that the process for an HTA is longer because of the need to request more information or clarifications from companies, as well as further assessment by independent academics. Unsaid, but important to remember, is that time is often health forgone for patients.

Decisions reached could also be affected if independent academics and the appraisal committees at NICE don’t thoroughly investigate concerns with the evidence submitted. What is again unsaid is that there’s a cost to ‘wrong decisions’, too.

View of academic experts

The quality of the clinical evidence submitted by companies to NICE was assessed by the authors drawing upon the critiques of the evidence available from academic groups that are commissioned by NICE.

For Single Technology Appraisals (STAs), they are known as Evidence Review Groups (ERGs). ERGs critique submissions made by companies. For Multiple Technology Appraisals (MTAs), Assessment Groups (AGs) instead review all the available evidence and report on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the treatments being looked at.

The team scored the clinical evidence reflecting the comments made by the ERGs and the AGs. Osipenko et al recognise that their scoring is subjective. But it is also transparent; the scoring and the rationales are shared by the researchers in a public repository and can be checked by anyone.

An example of differing evidence-generation approaches

In addition to the evidence cited by Osipenko in their paper, Dan Ollendorf, back in November 2020, pointed to a specific case that helps to illustrate the issue of different clinical evidence to support later approvals. Ollendorf is currently chief scientific officer and director of HTA methods and engagement at the US-based non-profit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) and director of value measurement & global health initiatives at the Tufts Center for Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health (CEVR).

Ollendorf noted Genentech’s Hemlibra (emicizumab) 2017 regulatory approval for a subset of patients with haemophilia was based on what he described as “a reasonably rigorous Phase 3 RCT”, with 109 patients followed for at least six months. This compared emicizumab prophylaxis to no prophylaxis. A Phase 3 RCT of 152 patients supported an extension to the regulatory approval.

By 2020, a potential competitor emerged in BioMarin’s Roctavian (valoctocogene roxaparvovec), a gene therapy. Ollendorf pointed out that the evidence available for Roctavian was a single-arm Phase 1/2 study in 15 patients. At the time, Ollendorf was commenting, there was an ongoing Phase 3 trial in 134 patients, but without a comparator.

Ollendorf pointed out how this is the same target population, but very different strategies for evidence generation. Whilst he acknowledged there could be reasons for that which might not be known, he concluded that “what is clear is that the regulator imposed very different evidence standards in these situations, and HTA is left holding the bag.”

Can NICE drive better evidence?

Osipenko and colleagues call for efforts to be made pre-market to “maximise relevant data generation.” Easy to say, but hard to do because companies are generating evidence to support regulatory approval, often for multiple regulators, and even more HTA agencies and other decision-makers who influence market access.

What evidence each agency accepts can differ. Generating better evidence for NICE might not be enough of an incentive, given that non-submissions at NICE have been on the rise and the UK, whether the politicians like it or not, has become less attractive in recent years.

Any evidence generation comes at a cost, too. However, a stronger incentive to improve the clinical evidence base for HTA may come from European efforts through joint clinical assessment in the future, a change that Osipenko et al discuss. That’s because a better evidence base could help achieve access across more countries, in theory at least.

The authors also note that NICE has offered scientific advice since 2011, “encouraging companies to think carefully about their development plans, design high-quality trials, and collect robust data for the appraisal process at NICE.” Osipenko was director of NICE Scientific Advice from 2014 to 2018, so she will have the inside track on those confidential discussions. Joint clinical consultations in Europe in the future are also touched upon in the article.

It seems plausible that NICE advice – or indeed advice from other HTA agencies, too – could improve the quality of clinical evidence if it’s acted upon. Still, it’s currently not possible to explore with any meaning. There are some early insights on NICE advice and some data available on the scale of scientific advice projects, sourced via Freedom of Information requests, but it’s not known which TAs these apply to, even assuming that NICE advice was always acted upon by companies.

In short, more transparency is needed: why can’t NICE set out as part of the TA when advice has been sought? It would not need to reveal what the advice was, or whether it was followed, and would align with the way that EMA reports on advice as part of their regulatory approach. That would be a step in the direction of being able to test what difference scientific advice from HTA agencies can make to the evidence that is generated, a missing piece that would complement the Osipenko et al analysis.

An ongoing debate

The industry could take issue with the subjective scoring, as well as the views of the AGs and ERGs that Osipenko and others have drawn upon. Still, their analysis contributes to an ongoing debate on evidence standards for treatments.

It is also an impressive amount of work, rather than anecdotes. The message from the Osipenko et al research is that the industry needs to do better, but does the industry have enough incentives to do it?