20 people who shaped healthcare in 2014 (Part 1)

Andrew McConaghie looks back at 2014 in healthcare and pharma, and a selection of diverse people who proved influential over the course of the year.

Part One

1. Pete Frates – the man behind the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge

2. Barry Werth – author of The Antidote

3. Steve Miller – scourge of Sovaldi and pharma's high prices

4. Sir Paul Nurse – British science leader and critic of Pfizer's bid for AstraZeneca

5. Emile Ouamouno – Ebola's 'patient zero'

1. Pete Frates

The man behind the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge

Pete Frates and his wife Julie are determined to keep fighting for a cure for ALS

The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge was the most surprising internet phenomenon of 2014. While open to charges of internet narcissism, these videos of people throwing ice-filled water over their heads for charity transformed awareness of a devastating, incurable disease, and raised a remarkable $100 million-plus for research in the process.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), known as Motor Neurone Disease (MND) in the UK, is a rare neurodegenerative disease which typically strikes around the age of 60 and, on average, causes death within three to four years of diagnosis. There has been very slow progress in developing new treatments for the disease in recent years: just one drug, Sanofi's Rilutek (riluzole, launched in 1996) has being shown to affect the progression of the condition, but this is generally limited.

The idea of filming yourself having a bucket of ice cold water thrown over you, and then passing on 'the challenge' by nominating friends and associates, is thought to have started in relation to other good causes in 2014, before being adopted by ALS campaigners in America.

From there, the idea spread like wildfire across the US and the world via social media. By the time the craze had fizzled out at the end of August, around 2.4 million videos had been uploaded to Facebook.

But who started this 'viral' video hit for ALS? The answer is Pete Frates – who, despite the global spread of the #IceBucketChallenge via social networks, remains relatively unknown. Diagnosed with ALS in 2012, Frates was determined to fight the disease by raising awareness, and succeeded in his goal of persuading Bill Gates to douse himself with ice cold water. This, and other celebrity endorsements, helped the philanthropic craze to go global. It had much in common with other health related 'memes' such as the #nomakeupselfie for cancer research earlier in the year, but the scale of the funds raised, and its success in hugely elevating the profile of a rare disease, set it apart from other viral hits. Misgivings about the phenomenon, including it being frivoulous and short-lived were understandable, but its potential to accelerate research into a cure is hugely significant. It is now crucial that progress is made for Pete Frates, as his condition continues to deteriorate.

Watch Pete Frates's mother Nancy Frates describe how the Ice Bucket Challenge began. Pete can be found on Facebook and on Twitter, where he continues his campaigning for a cure.

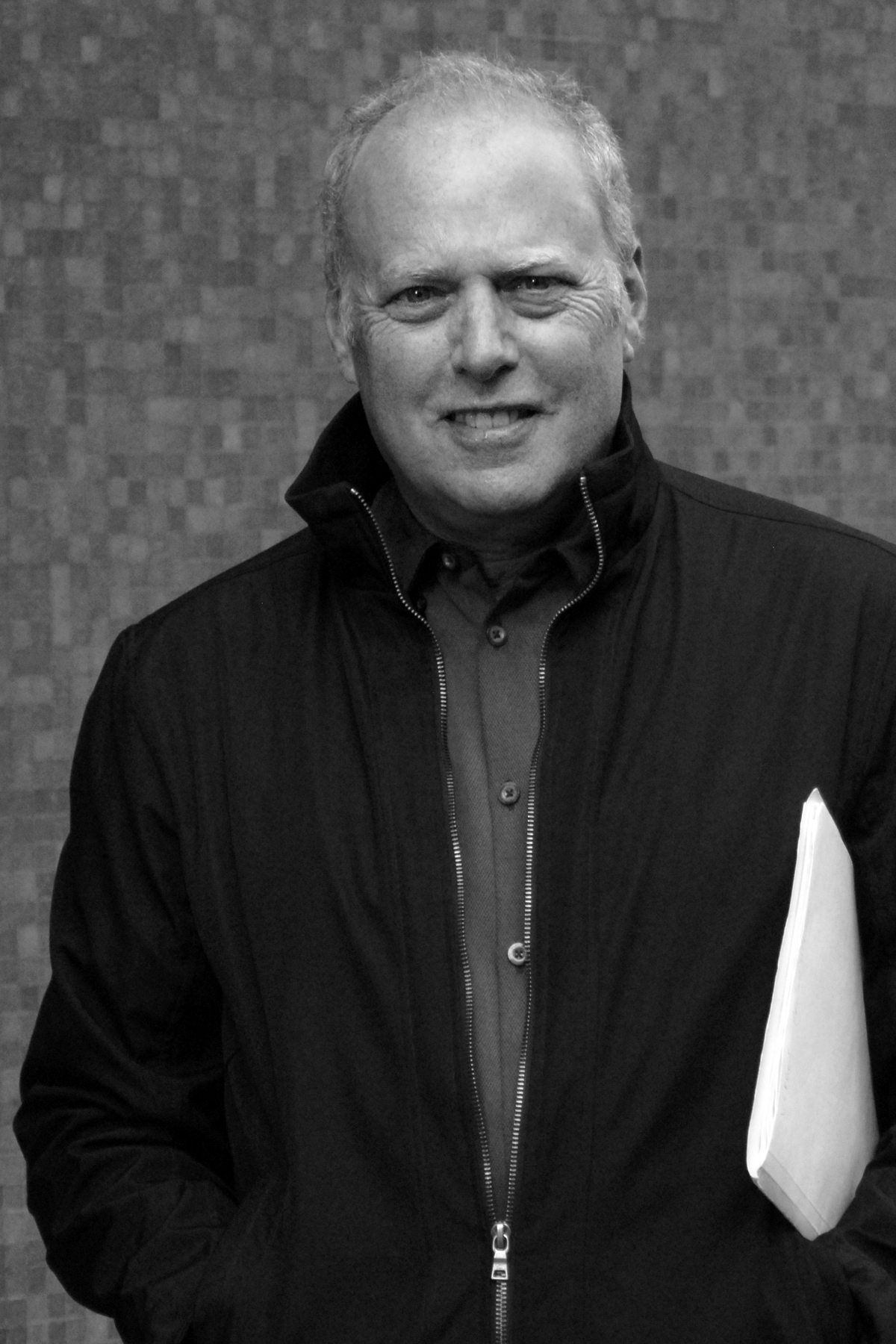

2. Barry Werth

A writer's masterful portrait of how science, business and human stories combine in modern drug development

Journalists are rarely mentioned among the annual lists of 'most influential' people in healthcare, but Barry Werth made a magnificent contribution in 2014 with his book The Antidote.

The book is a fly-on-the-wall account of life inside Vertex, the Boston-based specialist pharma company, in which Werth 'embedded' himself, charting its many highs and lows over an 11-year period up to 2013.

The Antidote paints a vivid, detailed picture of life inside the company, whose inspirational chief executive Josh Boger was determined to make a difference: "Make better drugs, faster. Create the 21st Century biopharmaceutical company. Become Merck, only better."

The Antidote is the sequel to Werth's book on the early days of Vertex, Billion Dollar Molecule

The book charts how Vertex's scientists and executives overcame huge obstacles to develop and launch groundbreaking hepatitis C drug Incivek – only to see it surpassed and made obsolete by the arrival of Gilead's Sovaldi, just a matter of months after its own launch. Also dramatised is the remarkable story of cystic fibrosis drug Kalydeco. Developed in alliance with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation's 'venture philanthropy' funding, the drug is a genuine breakthrough, and the book shows how it could not have reached the market without boundless determination and great risk-taking.

Illustrating how treacherous and unpredictable both the science and business of developing drugs can be, and how idealism will almost inevitably clash with the drive to appease Wall Street, the book is a primer for anyone interested in what it really takes to develop a novel medicine. In 2014, Vertex took the humbling step of withdrawing Incivek from the market, such was the dominance of Sovaldi, and means that expansion of its CF franchise is vital to its future. The company is set to make a loss in 2014, demonstrating that launching a breakthrough medicine isn't always a guarantee of meteoric profits.

Werth's book doesn't take sides or create heroes or villains; instead it is a valuable contribution to the debate about how it might be possible to "make better drugs, faster". But the book makes it clear that unpredictable factors – most particularly human strengths and failings - are inseparable from the business and science of the pharmaceutical industry.

3. Steve Miller

Chief medical officer of Express Scripts and scourge of the 'unsustainable' pharma pricing policy

Gilead's hepatitis C drugs Sovaldi and Harvoni were undoubtedly among the biggest stories in pharma in 2014 – not just in their unprecedented success, but also because of the unprecedented conflict they generated between pharma and US payers.

Launched in December 2013, Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) is the first in a new generation of drugs which offer a cure for hepatitis C (HCV) – this makes it a true breakthrough in medicine, but it comes at a high price. Sovaldi costs $84,000 for a 12-week course of treatment, which works out as $1,000 per pill.

Gilead's chief executive John Martin has, quite rightly, been lauded for his business acumen in creating this phenomenal success – acquiring in 2011 Pharmasset, the company which discovered and developed Sovaldi, and then ensuring the drug's unprecedented success in the US and other developed markets. However it is the role played by Express Scripts' Steve Miller which has proven to be the most remarkable.

As chief medical officer of Express Scripts, the biggest US pharmacy benefits manager, Miller has huge influence over the future of what drugs get prescribed to which patients, and at what price. In 2014, Miller emerged as one of the most outspoken and powerful critics of the pharma industry's high price business model, a trend which has grown in recent years as pharma launches more high cost drugs in specialist disease areas.

"Never before has a drug been priced this high to treat a patient population this large, and the resulting costs will be unsustainable for our country," warned Miller in a statement released in April. "The burden will fall upon individual patients, state and federal governments, and payers, who will have to balance access and affordability in ways they never have had to before."

Gilead maintains that the cost of Sovaldi and Harvoni is justifiable because the US healthcare system will be spared the cost of treating patients with advanced liver disease, including the very costly liver transplants some patients will undergo. While there is merit in this argument, US health insurers will face a hugely increased bill for treating HCV patients, which must be paid up front. Gilead also raised ire among health insurers by refusing to offer a price discount, commonly as big as 20 per cent.

Despite this opposition, Sovaldi has been a huge hit, enjoying the most successful launch ever of a pharma product, racking up $5.75 billion in sales in the first six months of 2014 alone. This skyrocketing trend actually fell back in the third quarter, but this is explained by the arrival of Harvoni in October, which, remarkably, is set to eclipse Sovaldi.

A combination of sofosbuvir with a new drug, ledipasvir, this two-in-one pill is the first approved regimen that allows treatment without interferon or ribavirin. For that reason, Harvoni represents a final stage in the transformation of HCV treatment in doing away with interferon and ribavirin. These drugs can cause very severe side effects, including nausea, diarrhoea, itchy rashes, insomnia, and severe depression, which frequently deter people from seeking treatment, or cause them to stop taking the medication prematurely. This extra progress means that the drug is even more expensive than Sovaldi, costing $95,000 for a 12-week course of treatment. However, given that this price is similar to Sovaldi plus interferon and ribavirin, and that patients on Harvoni often take less than 12 weeks to be clear of the virus, it is viewed as no more costly than Sovaldi.

What Steve Miller and others have been waiting for all year finally arrived in mid-December: a rival to Harvoni, in the shape of AbbVie's Viekira Pak. AbbVie's official price isn't much lower than Harvoni - $83,319 for a 12-week regimen, just 12 per cent less than Harvoni, and only slightly less than Sovaldi alone. Given that AbbVie's treatment requires patients to take four pills instead of just one for Harvoni, the drug is less appealing to patients and doctors than Gilead's drug.

However Express Scripts has just announced that it has secured a major discount from AbbVie for its National Preferred Formulary, a list of drugs reimbursed for 25 million Americans. This means Express Scripts will be dropping Harvoni from its formulary for patients with the genotype 1 variant of the disease, the most common in the US and the most difficult to treat. However, the arrival of Viekira Pak is far from being the end of the story. Conflict between pharma and payers will continue, particularly in the US, where prices of some drugs already on the market have continued to rise well above the rate of inflation in recent years, alongside the arrival of new high-priced medications.

Miller says: "The current pricing mentality around innovative products is unprecedented and unreasonable," and many agree, including people within the industry. But nobody knows just when the breaking point may come, and in what form. US health insurance bodies are using a number of methods to try to stem costs related to new HCV treatments, including limiting access to the drugs – explicit rationing of treatments which was once seen as unacceptable. Pharma companies with drugs as genuinely groundbreaking as Sovaldi and Harvoni will always be rewarded, but medicines with more modest claims could get frozen out very quickly.

Read Steve Miller's blog post on Harvoni from October.

4. Sir Paul Nurse

Nobel Prize winner speaks out against Pfizer bid for AstraZeneca

The takeover bid mounted by Pfizer for UK-based AstraZeneca (AZ), which eventually rose to £69.5 billion ($118 billion) became a hugely significant issue in May – not just for the global pharma industry, but for the whole UK life sciences research sector as well.

The well-understood reasons of scale, savings and synergies were behind the bid, but even more prominent was 'tax inversion' - the chance for Pfizer to sidestep billions of US corporate taxes. This, combined with Pfizer's track record in squeezing out synergies by shutting research centres, created huge opposition to the bid in the UK.

Taken by surprise by demands for guarantees on long-term investment in R&D, Pfizer committed itself to maintaining AZ's existing base for five years, but this limited pledge only fuelled scepticism about its motives.

What was remarkable was that the attacks weren't confined to the predictable groups of certain politicians and union leaders, but also to leaders of academic medical research. Perhaps most prominent among those who raised objections was Sir Paul Nurse, a Nobel Prize-winning geneticist, President of the Royal Society and Director of the Francis Crick Institute.

Ahead of a public inquiry by two separate UK parliamentary committees, Sir Paul wrote a letter to the chairmen of the committees, saying Pfizer's commitments were "vague, come with caveats and have an inappropriate timescale".

Sir Paul said a five-year commitment to the UK was "insufficient", adding: "A commitment of 10 years is required. Science is not a quick-win sector - it requires long-term investment".

Nurse's intervention was not decisive on its own, but his reputation added hugely to the belief that Pfizer's bid should be resisted because it would undermine the UK research base. It was also testament to a great shift in pharmaceutical research, illustrating that the pharma and biotech sectors' research efforts are now inextricably interconnected - with academic researchers in the UK (or any country) needing a strong pharma sector, and vice versa.

Sir Paul is one of the leaders behind The Francis Crick Institute, a new multi-disciplinary medical research centre opening in London in 2015. The centre will aim to break down the barriers between disciplines in academic research and bridge the gap between this work and pharma and biotech research. Read more about The Francis Crick Institute here.

5. Emile Ouamouno

The boy named as Ebola's 'Patient Zero'

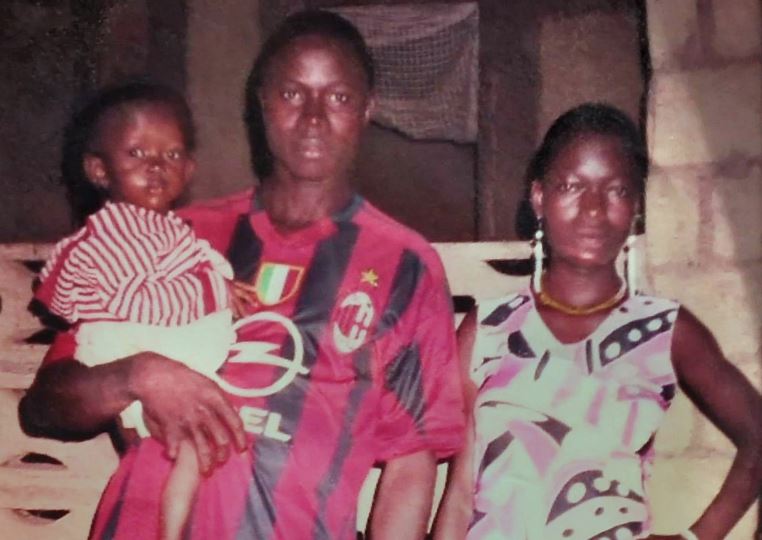

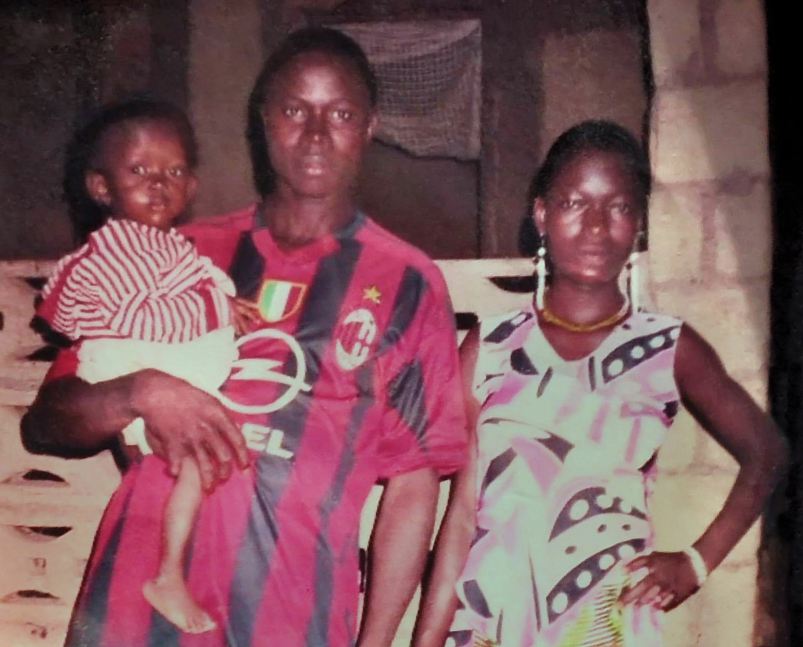

Emile pictured with his parents

The devastating Ebola epidemic has claimed more than 5,000 lives across West Africa, and is still not fully under control after first emerging in December 2013.

In October, researchers looking to understand how the deadly virus spread, traced the origins of this outbreak to one village in Guinea, Meliandou, and to one little boy: Emile Ouamouno.

Emile was the first person to die in the outbreak, but researchers weren't able to discern how he contracted the disease. His mother, four-year-old sister and grandmother were then next to be claimed by the disease, before it was transmitted onwards and out to the wider region.

Being able to pinpoint Emile illustrates just how some scientific techniques have advanced – and yet this precision is a sadly ironic contrast to the inability of governments and health experts to halt the disease at an early stage.

Emile's story also exemplifies the truth about preventable diseases in developing regions: children under five are overwhelmingly the victims of terrible diseases such as Ebola and, much more commonly, preterm birth complications, pneumonia, birth asphyxia, diarrhoea and malaria. A total of 6.3 million children under the age of five died in 2013. Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 15 times more likely to die before the age of five than children in developed regions.

And as West Africa's Ebola epidemic has shown, even those children spared infection are at risk of being orphaned, and can face stigma associated with the disease.

Read the Unicef blog, Ebola: finding patient zero

Read Part 2 of 20 people who shaped healthcare in 2014 including Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England.

About the Author

Andrew McConaghie is pharmaphorum's managing editor, feature media.

Contact Andrew at andrew@pharmaphorum.com and follow him on Twitter.