Using social media for clinical trial recruitment

In this fourth of her series focusing on social media in healthcare, Leanne Orchard explains the opportunities for increasing recruitment to clinical trials through engaging with online patient populations.

It is no secret that recruiting patients for clinical trials through the traditional avenues is costly, time-consuming and often unrewarding. As a grim reminder we need only look at recent statistics that paint a less-than-optimistic picture:

• Patient enrolment rates fell from 75% in 2000 to 59% in 2006, with a 21% drop in retention over the same period

• 15-20% of trials never manage to enrol a single patient

• 37% of all sites in a given trial fail to meet their enrolment targets

• Nearly 30% of the time dedicated to clinical trials is spent on patient recruitment and enrolment.

In an increasingly digital age it seems that the old ways of relying on physician recommendation or advertising and targeted email campaigns may need supplementing. As InVentiv Health explains in its white paper on e-recruiting, 'Competition for trial subjects is intense. This is the case because regulatory agencies are demanding more, larger, and longer studies and because therapies are increasingly targeting niche populations [...] There are only so many potential subjects fitting the target profile for any given study to go around. And when a study calls for treatment-naïve patients, the available pool of patients can shrink dramatically.'

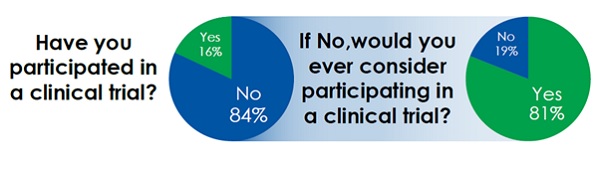

How, then, can social media help isolate these target patient populations? The previous article in this series looked at how online patient communities across a variety of platforms could be used to map the patient journey more effectively and touched upon how these same communities provide a hub of target patient activity for health care providers to utilise for patient recruitment. In a study conducted by Blue Chip Patient Recruitment into the attitudes and behaviours of those actively engaged in online healthcare communities, it was found that, though the majority of those questioned had not participated in a clinical trial before, they reacted positively to the idea of getting involved.

Surely then it makes sense to take recruitment to where the patients are and push them to registration pages rather than hoping they will be pulled in by awareness campaigns and physician referral? This is not a new idea and is currently being employed by a number of companies to help improve recruitment and retention.

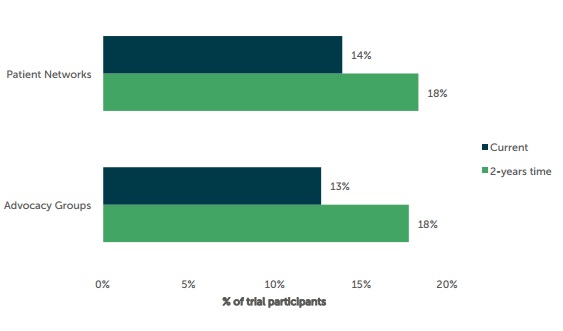

In fact, a study conducted last year by Industry Standard Research predict that by March 2016 advocacy groups like those discussed will play an even bigger part in patient recruitment, as the graph below suggests.

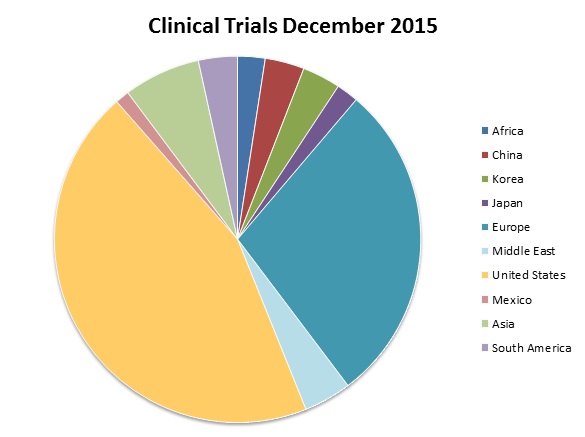

But as discussed in the previous section on patient-centricity, it is not just as simple as rolling out one universal strategy; language and culture play a huge part in whether a patient will be open to being recruited into a clinical trial. This is especially important when we consider that in the never-ending search for fresh, treatment-naïve patients to enrol in clinical trials, sponsors are expanding their international reach and looking to host more trials in new regions across the world.

As of December 2015 there were 204,041 clinical trials registered with clinicaltrials.gov worldwide, as can be seen below. On 6 December this year it recorded a total of 36,879 studies recruiting, of which 46% were recruiting patients exclusively outside the US.

Despite reaching out into new territories, most trials rely heavily on traditional methods of patient recruitment, such as flyers, posters, radio and television ads, as well as counting on physicians and investigators to promote the trial directly to potential patients. As recently as 2013, the Tufts Centre for the Study of Drug Development reported that nearly 100% of the studies conducted outside North America in that year used such methods.

The first article of this series pointed to Novartis as an example of a company which is doing all the right things with social media, and this carries through to its patient recruitment. The Novartis Clinical Trials website allows visitors to access lists of clinical trials taking place worldwide and provides users with an interactive tool for finding relevant trials taking place near their location or, indeed, anywhere in the world, allowing them to search by criteria important to them. Unlike @NovartisCancrUS, which is limited to the US, this platform is aimed at a global audience and utilises location technology to display the clinical trials geographically closest to the visitor.

In another example a manufacturer recruiting for a clinical trial into treatment of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) created a well-designed website, ad placements via Google and Facebook as well as an introductory video on YouTube. By the third month of the digital ad campaign, traffic to the trial website had increased by a staggering 6,474%, with the three-month Facebook ad campaign providing 64% of the site's visitors. Within three months, the website received nearly 70,000 visitors who reviewed one or two pages of content, and the trial was completely enrolled in four months.

A key statistic to consider when aiming to roll-out a social media-based e-recruiting strategy is that 70% of internet users are not native English speakers. In order to engage meaningfully with patients on an individual level you will need to have information on local trials available in local languages.

However it is not enough to ensure that recruitment materials are translated word for word. Even if translated material reads as though it were written by a native speaker of the target language, recruitment messaging can often be overlooked if it does not make use of readily recognisable terminology; often it can be the case that an exact medical term for a condition is not the name used by the general population. As an example, while the medical term 'psoriasis' is used by the medical community, the common term used by the general population in Germany is 'shuppenflecht'. As such, recruitment materials that rely too heavily on the term 'psoriasis' without mention of 'shuppenflecht' may miss a wide audience of people with the condition who simply do not know or think to search for it under any other term.

Additionally, different countries may have different legal restrictions when it comes to the wording of reimbursement clauses for participation in trials and others may reject the wording 'clinical trial' altogether. In such instances a straight translation without understanding local regulations can result in disaster. To avoid these pitfalls, expert help should be sought.

With access to a plethora of information on healthcare, diagnosis and symptoms at the click of a link, today's patient is more informed, more empowered and, ultimately, more demanding. If there is no treatment available for a particular condition, they are more likely to push for targeted trials.

The final instalment in this series will discuss crowdsourcing in healthcare and its implications for the industry.

About the author:

Leanne Orchard is a Language Solutions Executive in SDL's Life Sciences Solutions division.

SDL is a provider of language, technology and business intelligence solutions to international pharma and medical device companies and contract research organisations.

Leanne can be reached on lorchard@sdl.com or +44 (0) 1142 535 337.

Read the previous article in this series: