Ultra-rare disease drugs: has access in England just got harder?

New rules on market access introduced by NICE from 1 April will affect most new medicines – but gaining access to ultra-orphan drugs could become much more difficult.

On 1 April this year, NICE introduced a raft of measures aimed at controlling the entry of new medicines on to the national health service in England.

Most important of these is the budget impact test, which adds a new affordability test to any drug expected to cost the NHS more than £20 million in any of its first three years on the market.

This will involve an additional discussion between NHS England (which controls the budget for specialised therapies) and a pharma company about cost and affordability.

This represents a new level of involvement in market access of NICE-approved medicines for NHS England; something it says is necessary to control expenditure and market entry on high cost drugs, but which pharma and patient groups claim will add further delays to access to new medicines.

What spurred the introduction of the new budget impact test was the arrival of new hep C drugs, such as Gilead’s Sovaldi, in 2014. The high cost of the drugs, combined with the large number of patients meant annual costs could (theoretically) have been at a budget-busting £500 million a year.

The new test formalises the approach NHS England took with the hep C drugs, allowing it to negotiate with pharma companies on price, or otherwise delay or phase market access for up to three years.

Meanwhile, NICE’s system for ultra-orphan drugs, the Highly Specialised Technologies (HST) appraisal, is also undergoing major change.

This will involve introducing a new ‘QALY modifier’. This creates a new range of £100,000 up to £300,000 per QALY for highly specialised technologies which demonstrate greater than 10, to greater than 30, incremental QALYs, respectively.

Pharmaceutical companies and patient organisations have been in no doubt that these changes could further limit or delay access to drugs in England, specifically (including) ultra-rare treatments.

NHS England and NICE are playing down the changes, saying the budget impact test is merely an opportunity for a conversation around price, and they have pledged flexibility around the new system for HSTs.

A recent pharmaphorum webinar brought together some of the key stakeholders in rare disease market access to discuss the changes, and see how all sides can work together to ensure patients gain access.

Change the language from ‘but’ to ‘and’

Angela McFarlane, market development director at QuintilesIMS, is one of the leading experts on market access and orphan medicines in the UK, working closely with pharma companies and health service organisations such as NHS England.

[caption id="attachment_15792" align="alignnone" width="135"] Angela McFarlane[/caption]

Angela McFarlane[/caption]

She says the last 10-15 years have seen some great advances in care brought about by orphan and ultra-orphan drugs, such as cancer treatment Glivec, treatments for Pompe disease and for cystic fibrosis.

She acknowledged that a new generation of rare disease drugs is testing the system.

“This is an evolving space. We didn’t have these challenges 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago, so we are all learning together.”

However, she made a plea for a change in the language used by NHS decision makers to make rare diseases a ‘but-free’ zone.

“Whatever comes after the word ‘but’ will be the crystallisation of reasons not to fund a medicine, and steals the opportunity to change life outcomes for patients with rare diseases,” she says.

“We need to replace 'but' with ‘and’ wherever possible.”

In other words, solutions to the affordability issue need to be found, rather than excuses for not providing access. She says some outdated attitudes remain: such as the ‘old chestnut’ that orphan disease drugs take away funding from medicines which can help a far larger groups of patients.

McFarlane also recalled one NHS regional leader who compared paying for orphan medicines to rescuing beached whales: “expensive, doomed to fail, but fuelled by a wave of public emotion.”

She says such attitudes stand in the way of greater progress, which will require more dialogue, transparency and adoption of new approaches to address risk, such as the systematic use of real-world evidence (RWE).

NHS England – focused on affordability

Malcolm Qualie is the pharmacy lead at NHS England specialised commissioning.

He agreed that new treatments had brought about major improvements for patients with rare diseases in recent years, but emphasised the challenges these new products create for payers such as NHS England.

[caption id="attachment_25925" align="alignnone" width="150"] Malcolm Qualie[/caption]

Malcolm Qualie[/caption]

“The issue that we have with [ultra-rare] medicines is that because the EMA speeds them through the system, the evidence we have on those medicines isn’t quite as good as it is on cardiovascular medicines or diabetes medicines, for example."

The evidence collected for these drugs remains “quite basic,” he says, often relying on surrogate markers which give no clue to their impact on long-term outcomes in 10-15 years’ time.

NHS England is concerned about the ever-increasing cost of specialist, secondary care medicines.

“Spend in secondary care has gone up by 16% every year for the last three years. The data currently shows a big gap between what we spend in primary care and what we spend in secondary care, but those two curves are going to cross in the next few years.”

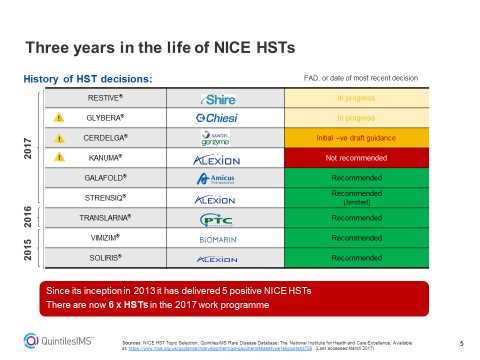

Figure 1: An overview of NICE decisions on Highly Specialised Technologies, including those already made and those pending.

The rare disease patients’ perspective

Alastair Kent is ambassador for the Genetic Alliance UK, and is one of the country’s foremost campaigners for rare disease patients.

He agrees that NHS England is in a very difficult position, and that a finite budget clearly means you can’t pay for all treatments and services.

However, he says the new rules will hit access to rare disease drugs hard.

[caption id="attachment_25924" align="alignnone" width="175"] Alastair Kent[/caption]

Alastair Kent[/caption]

“Unfortunately, the new system seems to be designed to discourage innovation, and to restrict patient access.”

He adds: “Changes to the process for evaluating very small population high cost drugs have set the barriers at an unreasonably high level. Since 2013, NICE’s HST committee has said yes to five therapies – but none of those would get the go-ahead under the new criteria.”

He said this new squeeze on access to novel treatments contradicts government messages about encouraging innovation uptake on the NHS.

“On one hand, you have the Accelerated Access Review saying “bring your research and development to the NHS, we want to make it the place for world class opportunities to develop innovative medicines for serious unmet health needs in rare diseases.”

“But on the other hand, you have got the barriers being erected such as the £20 million budget impact test, which will delay patients’ opportunity to benefit.

“It seems to us like there is a lack of joined up government here and there should be a clear message across the piece.”

He concluded: “Imagine you are a boy with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), where your life expectancy on average is around 20 years. Imagine the impact if NHS England says that because of the budget impact, we want to delay availability by up to three years.”

He says a three-year wait would be a substantial part of that boy’s life, making such a delay completely unacceptable.

Malcolm Qualie responded to this, saying each drug will still be reviewed on its own merits, and that the £20 million is a trigger point for discussion, not a threshold.

The NICE perspective

Sheela Upadhyaya is Associate Director at NICE, overseeing its HST appraisals.

She says she welcomes the new QALY weighting method range as, until now, the HST programme had no threshold to indicate what represented fair value for the NHS.

[caption id="attachment_27286" align="alignnone" width="160"] Sheela Upadhyaya[/caption]

Sheela Upadhyaya[/caption]

“I can’t tell you how hard it has been to do that without a clear framework - I think companies that have been part of that process would identify with that.

“Without a framework, you are potentially shooting in the dark – no company, patient group or NICE had a target to aim for.”

She stressed that NICE and NHS England responded to stakeholder concerns about the initial proposal to impose a £100,000 threshold on HSTs, and instead created the £100,000-£300,000 range. Drugs for very rare diseases will be evaluated against a sliding scale, so that the more additional QALYs (a way of measuring benefits to patients) a medicine offers, the more generous the cost per QALY level it will need to meet.

Upadhyaya pointed out that two recent HST approvals, Translarna and Vimizim were introduced with special Managed Access agreements. NICE expects that similar managed access agreements can be agreed for more rare disease product that show promise.

“The budget impact test allows that collaboration to happen early on in the process. I know companies are willing to engage with us if their product can demonstrate value,” she added.

If NHS England does request to delay implementation of NICE guidance via the budget impact test, NICE will have to approve this, and will demand robust evidence to support the decision.

Stakeholders will also have an opportunity to comment at this stage.

“It’s important to flag that the process will have these checks and balances…but I won’t lie, it is going to be challenging, and the orphan drug space is getting bigger and bigger,” she concluded.

Asked to sum up their thoughts, both NHS England’s Malcolm Qualie and NICE’s Sheela Upadhyaya were upbeat about the new process.

Angela McFarlane said the spirit and intent was present, but reiterated her call for a switch of language from ‘but’ to ‘and’ to overcome barriers to access.

However Alistair Kent said he believed the new procedures would be “slow and cumbersome.”

“Are we moving in the right direction? I think it’s too early to say. We will be watching you [NICE and NHS England] and looking at the decisions made, what has been taken into account, how long it takes to make those decisions, and how they are implemented.”

Wryly adapting Angela McFarlane’s quote about ‘beached whales’ he concluded:

“Not all beached whales die – many are successfully helped back into the water and go on to live long and happy lives. Let’s hope those are the ones you can pick out in your new process.”

Watch the full pharmaphorum webinar here: When small becomes big: orphan medicines, advances, access and affordability.