The underrepresented in clinical trials: a US perspective

Rebecca Budd

Navita Clinical Strategy Group

Rebecca Budd shares her opinions on some of the reasons behind underrepresentation in clinical trials in the United States, from both a patient and a sponsor perspective. She also provides her thoughts on the future of clinical trials for the pharmaceutical industry, if they continue in the same way.

Twenty years ago, clinical trial participants in the United States were homogeneous. Participants were overwhelmingly males, and White males at that1. Times have changed – but only to some extent. Although clinical trials are more diverse now than ever before, there continues to be a significant gap in clinical trial participation by minority subpopulations in the US. This includes racial and ethnic minorities, women, children, and the elderly.

The globalization of clinical trials has contributed to greater diversity in clinical trial participants. But it is not helping the problem of underrepresentation in US trials. The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development estimates that nearly half of all FDA-regulated trials are conducted overseas – rising from only 14% in 1997 to 47% in 20092. With fewer trials being conducted in this country, the absolute number of US minority participants is not increasing, even if there is an increase in the percentage of minorities participating.

Why does diversity in clinical trials matter? First, certain medical conditions disproportionately affect certain groups. For example, African Americans on average are twice as likely as Whites to develop diabetes. Hispanic Americans are on average 1.7 times more likely than Whites to suffer from the disease3. Second, race and ethnicity can impact the efficacy of drug treatments. In the early 1980s, for example, it was observed that different ethnic groups had different responses to the blood pressure-lowering properties of beta blockers4.

,

"Should patient enrollment for clinical trials be representative of the US population or the disease population?"

,

The problem of underrepresentation in clinical trials is becoming even more serious. This is because minority populations are expected to be in the majority by 2050. If pharmacological research continues to be dominated by mostly White male patients, the results of the research may not be applicable to other groups and the patients in those groups may not reap the benefits of modern science5. With that possibility in mind, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) now require government-funded research to be more inclusive of women and individuals from minority groups in a manner appropriate to the scientific question under study (NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, PL103-43).

How to determine appropriate representation

Should patient enrollment for clinical trials be representative of the US population or the disease population? And what effect does globalization have on the equation?

On the topic of appropriate representation, the authors of Ethnicity in Drug Development and Therapeutics5 noted:

“In deciding the extent to which minorities should participate in clinical research, one should consider the scientific question being addressed, and the prevalence of the disease / disorder in ethnic / racial populations relative to the population as a whole5.”

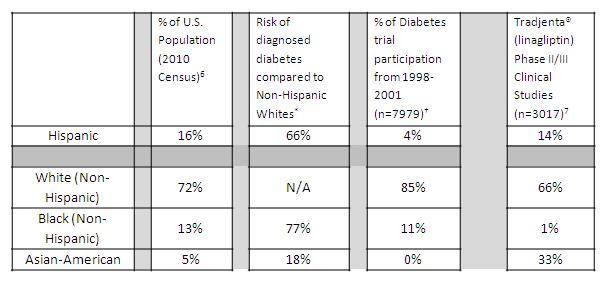

Let’s consider some specifics. As shown in the figure below, Blacks comprise 13% of the US population and have a 77% risk of being diagnosed with diabetes compared to non-Hispanic Whites. In a review of diabetes trial participation from 1998-2001, 11% of participants were Black. But in nine pivotal Phase II / III efficacy clinical trials for the diabetes drug Tradjenta® (linagliptin) approved by the FDA in May 2011, only 1% of study patients were Black.

Figure 1: Author Note: This chart is not meant to show direct comparison but to highlight the disparities among various racial/ethnic groups.

*After adjusting for population age differences, 2007-2009 national survey data for people diagnosed with diabetes aged 20 years and older. Source: 2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet (released January 26, 2011). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates11.htm

†US diabetes trials participants, FDA 1998-2001 (n=7979). Represents 80% of known US diabetes trial participants. Race / ethnicity could not be determined from the integrated summaries for the remaining 20%. Evelyn B, Gray K, Rothwell R (Office of Special Health Issues US FDA). US Black participation in clinical trials: a review of selected new molecular identities approved 1998-2001. Presented at the NMA meeting, 2002, Honolulu, Hawaii.

As a whole, these studies of Tradjenta® (linagliptin) do not accurately reflect either the demographics of the US population or the demographics of diabetes in the United States. Also, notice that a high concentration of Asians participated in these studies, in contrast to the relatively low percentage of the US population that Asians comprise. The high Asian participation turned out to be because many of the study sites were located outside the US in countries such as China, India, Malaysia, and Thailand.

It is important to note that research results from overseas trials cannot necessarily be extrapolated to patients in the United States. A Chinese person living in China is not the same as a second generation Chinese American living in the US. The medical care available in both countries is different as are the diets, health habits, and culture.

,

"It is important to note that research results from overseas trials cannot necessarily be extrapolated to patients in the United States."

,

Why does underrepresentation exist?

The issue is very complex and the reasons are multi-faceted. Here’s a brief list of some commonly cited reasons:

Patient issues

• One reason is lack of awareness. Individuals who are not part of the healthcare system or have not seen information in the media may never hear about clinical trials for which they could be eligible.

• Cultural and language barriers affect decision making. First-generation Hispanics, for example, often involve other family members to help them understand their treatments and include family in the decision to participate.

• Some ethnic populations also harbour uncertainties about and / or mistrust of healthcare providers, which might make them less likely to want to participate.

Sponsor issues

• A study protocol designed without insights on cultural competency may unintentionally create minority-specific barriers to participation. For example, BMI restrictions will have a greater exclusionary effect on Blacks and Hispanics than Whites. In general, these groups have diets high in fat and fuller figures are more socially accepted, leading to higher rates of obesity.8

• Another possible barrier is a complex protocol. If it’s too burdensome (too many tests / appointments, electronic diaries, special diets, etc...), potential participants may be concerned about being able to meet study requirement while keeping up with work and home.

• Study sponsors often fail to select enough investigative sites with track records of proven success in recruiting minorities, or they choose sites that are not conveniently located to minority neighbourhoods.

• Recruitment tactics designed to appeal a general population (such as media campaigns or internet recruitment) are often not relevant to or effective in reaching subgroups such as Hispanics, Black, or low-income participants.

Industry sponsors are the key to improving representation

It’s clear that there is much still to be done to increase the participation of underrepresented subgroups in clinical trials. The pressure from the NIH and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will only continue, especially in light of the growing minority population in the US.

To achieve sustained improvement, industry sponsors must take the leadership position and revisit the current model of conducting clinical trials. The following suggestions are food for thought for sponsors to address this growing problem.

• Cultural competency strategists can provide critical insights into how cultural attitudes, behaviours, and social norms affect clinical trial participation among diverse population groups. Their involvement early in the process may help accelerate recruitment.

,

"It’s clear that there is much still to be done to increase the participation of underrepresented subgroups in clinical trials."

,

• Protocol design should quantify (if possible) potential barriers to underrepresented subgroup participation and make modifications where possible.

• Site selection should be restructured to identify and select sites with a strong history of successful minority recruitment. The ability to enroll and retain patients from underrepresented populations should be part of every feasibility questionnaire.

• Population-specific clinical trials, conducted in the US, provide valuable information on the potential treatment response differences between minorities and Whites. They can also make up for significant shortfalls in minority subgroup representation in earlier trials. The manufacturer of Tradjenta® (linagliptin) recently announced results of a race-specific efficacy and safety trial conducted in the US that enrolled 225 Black patients9.

• Study budgets for sites with proven track records for minority participation should be appropriately adjusted since the estimated costs of enrolling minorities is estimated to be 15% to 20% higher than enrolling White patients10.

• CROs should be encouraged (or required) to make enrolment of diverse populations a priority. With proper incentives, CROs can strengthen their internal operations to improve site selection and provide appropriate site support to sites enrolling minority patients.

Forward thinking

Underrepresented populations in clinical trials face numerous barriers to participation and there is an urgent need to find a lasting solution for this continuing problem. This article highlights some of the barriers to participation and the negative impact of globalization. It provides suggestions that will require the pharmaceutical industry to take a leadership position in altering the current clinical trial process. Increasing participation of patients from diverse populations will strengthen the industry’s ability to truly provide effective treatments for all.

References

1. Dresser R. Wanted single, white male for medical research. Hastings Center Report. Jan-Feb 1992, 22(1):24-29. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3562720?uid=3739656&,uid=2129&,uid=2&,uid=70&,uid=4&,uid=3739256&,sid=47699095726887. Accessed June 20, 2012.

2. Korieth K, Anderson A. Site landscape shrinking, losing most active PIs. CenterWatch Monthly, January 2012, 19(1):13.

3. Diabetes data / statistics. The Office of Minority Health / US Department of Health and Human Services. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&,lvlid=62. Accessed June 20, 2012.

4. Johnson JA. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular drug response: potential contribution of pharmacogenetics. Circulation.2008, 118:1383-1393.

5. Frackiewicz EJ, Shiovitz TM, Stanford SJ. Ethnicity in Drug Development and Therapeutics. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

6. Humes KR, Jones NA, Ramirez RR. Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2012.

7. Tradjenta package insert, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company.

8. Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, et al. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. A consensus statement of Shaping America’s Health and the Obesity Society. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31(11):2211-2221.

9. Thrasher et al. Study of linagliptin in African American patients with type 2 diabetes. Presented at American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Annual Meeting, May 24, 2012, Philadelphia, Pa.

10. Agodoa L, Alanis AJ, Alexander-Bridges M, et al. Increasing Minority Participation in Clinical Research (White Paper) Chevy Chase, MD: Endocrine Society, 2007.

About the author

Rebecca Budd is managing director of Navita Clinical Strategy Group. Navita's mission is to increase participation of diverse racial and ethnic minorities in clinical research. The company provides sponsors, CROs, and sites with inventive solutions developed by integrating applied sociology, site/patient research and analytics, and patient population strategy into the overall trial process ? including protocol design, budgeting, site selection, and patient enrollment.

You may follow her comments on Twitter @RLBudd2 or contact her at rebeccabudd@navitastrategy.com.

How can we improve awareness of clinical trials?