The UK pharma market – Accelerating Access or still stuck in the slow lane?

Hundreds of novel medicines are expected to gain approval between 2016 and 2020 but will the NHS make the most of the best new drugs, or limit access and uptake as in previous years? Andrew McConaghie reports.

The recent annual IMS Health UK Market Access Summit brought pharma together with leaders from NICE, the Cancer Drugs Fund, patient organisation Genetic Alliance UK, the ABPI and expert commentary from the Health Service Journal to discuss the future of access to medicines in England.

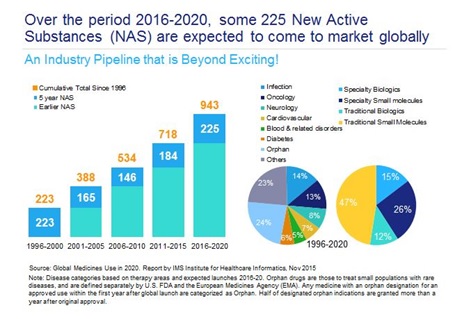

After many fallow years in the 2000s, the pharma and biotech sectors are now in the midst of a remarkable period, where the number of new drug approvals has risen sharply, and many genuinely innovative drugs are reaching the market. New treatments to cure hepatitis C, revolutionary immunotherapies for cancer patients, and novel therapies which, for the first time, will improve the lives of people with rare genetic conditions, have reached the market in the last few years – and there are many more potentially 'transformative' drugs in the pipeline (table 1).

But of course all this innovation comes at a price, and healthcare systems around the world are struggling to balance their budgets, thanks to increasing demand on services, including high priced drugs.

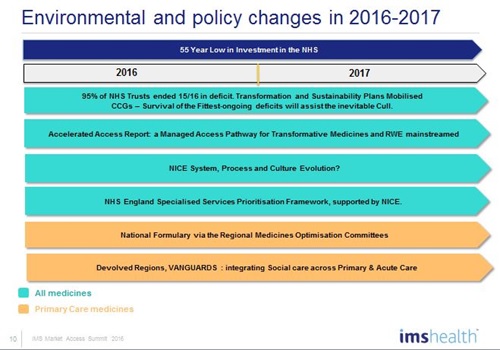

This pressure is acute in England, where the finances of the National Health Service (NHS) are deteriorating fast – 95% of NHS acute trusts ended the last financial year in debt, and this looks set to spread to Clinical Commissioning Groups. The sense of a system in crisis is heightened by health secretary Jeremy Hunt's long-running, and bitterly contested, dispute with junior doctors over the contract for a 7-days-a-week service.

Against this background, the pharmaceutical industry battles for access to its new drugs to be taken up in a system which, historically, has had more access hurdles than many other countries in respect of being slow to adopt innovation uptake and diffusion. Pharma and the wider life sciences industries are pinning their hopes on the forthcoming Accelerated Access Review (AAR) to address these obstacles to uptake.

Originally scheduled for publication in April, the AAR has now been delayed until after the UK's high stakes EU referendum on 23 June. Nevertheless, the pharma industry believes the AAR represents the best opportunity to embed innovation and its uptake into the NHS.

Call for a change of culture

Above all, there is a call for a change of culture, whereby the NHS could see the uptake of new medicines, devices, diagnostics and digital products as 'positive enablers', rather than cost overheads to be delayed or dodged. Pharma has a champion within government – Life Science Minister George Freeman – who is trying to spread this message. Mike Thompson, the new chief executive of UK pharma association the ABPI, says this synergy between the sector and the NHS can create a world-leading 'health powerhouse'.

But there is also deep scepticism in some quarters about the will of the NHS leadership and the government to prioritise this agenda – especially as Chancellor George Osborne's continuing austerity measures mean funding for the NHS is at an historic 55-year low.

Hosting the Summit, entitled '2016-2017: A defining year for UK pharma market access?' was Angela McFarlane, Market Development Director, IMS Health Market Access. McFarlane has been in the industry for 30 years, and a pioneer in the market access space for over 20 years, and sees the financial pressure on the NHS as unprecedented in her working lifetime. At the same time, she describes the medicines pipeline as 'beyond exciting' and retains some optimism about what can be achieved in the NHS 2016/17 financial year, which began in April.

While complete structural reform of the NHS is out of bounds, there is no shortage of major change programmes and initiatives in the coming year. In addition to the AAR, a revamped Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) will be launched on 1 July. The new CDF process proposed by NHS England will be aligned with an ever-evolving NICE. It will use a new 'conditional approval' mechanism underpinned by real-world evidence (RWE) to help avoid rejection of drugs with immature data but which otherwise have significant potential to advance treatment.

"My view is that the changes in access arrangements during the next year offer a unique opportunity to develop a collaborative, collective, accelerated patient access system," McFarlane told the industry and NHS audience. "But a culture change is also needed by all stakeholders, so that our innovative medicines are no longer viewed as 'affordability' overheads but are seen instead as investments."

McFarlane says the growing numbers of biosimilars now being launched represent a chance for the NHS to save money – and create 'headroom' for the uptake of innovative new drugs.

But IMS Health data shows that biosimilars uptake across England remains patchy. For instance, biosimilars account for 23% of infliximab prescribing – a reasonable level – but one that masks big regional variations. Only 23 hospital trusts in England had an uptake of more than 50%. McFarlane says these are missed savings, but they also represent a chance for pharma companies to assist the NHS with schemes (including RWE studies) to accelerate uptake.

NHS England tightens grip on costs

While there is optimism about the AAR, frontline UK pharma knows that NHS England is taking an increasingly firm grip on market access for specialised care drugs, by far the area of biggest growth.

Of particular concern is NHS England's new Specialised Commissioning Prioritisation Framework, which, many in pharma believe, will delay or reduce access to innovative specialist care drugs, and be used to exert pressure on prices.

Dave West, senior bureau chief at the respected Health Service Journal, confirmed that NHS England was pulling all the strings it could in order to maximise savings and minimise cost.

"My view is that three strategic priorities are likely to emerge this year: establishing financial stability, acute reconfiguration and adoption and spread of new care models as outlined in the Five Year Forward View," he said.

The Five Year Forward View (FYFV) is, of course, the strategic 2015-2020 plan put together by NHS England's respected, but under pressure, chief executive Simon Stevens. The FYFV makes it clear that the £20 billion of efficiency savings required up to 2020 can only be achieved by shifting to new care models, including the Vanguard pilot projects and newly announced regional Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs).

With so many urgent priorities for NHS leaders and frontline staff, there is a clear danger that the ambitious AAR report could end up being sidelined.

Professor Richard Barker is an ex-ABPI chief executive, chair of an Academic Health Science Network and health think tank CASMI and is closely involved in the AAR, having led its regulatory development workstream.

Talking in a personal capacity because the official AAR report is not yet published, Barker was, nevertheless, confident it would produce clear, actionable plans. These are likely to include "stronger patient engagement, joined up pathways for medicines and technologies, linking national and local agendas together, creating accelerated access for patients, and faster adoption by the NHS," he explained.

Barker believes a key proposal is the creation of a National Innovation Partnership (NIP), a standalone body to champion the uptake of innovation across the NHS. "If we can get it through, that will be one of the most important aspects of the AAR. The NIP is likely to include the Department of Health, the NIHR, the MHRA, NICE, NHS Improvement, NHS England, plus inputs from patients, charities, industry and so on."

'Flagship' products

The AAR chair, Sir Hugh Taylor has also indicated that around 5-10 new innovative technologies would be prioritised for rapid uptake under the plan. This would create 'flagship' products, but arguably not offer access solutions for drugs, devices and diagnostics not in this select group.

Another hugely important proposal contained in the report will be that for new flexible approaches to pricing and reimbursement.

Richard Barker added that 'affordability', not just cost effectiveness, is the real issue, and that industry should start thinking about formulae and 'novel financial instruments' that could shift costs away from being simply lump sum upfront payments.

He concluded: "The industry has to meet the NHS half way. That may seem unfair when your medicine is being reimbursed elsewhere in the world, but it is the reality of the situation here in the UK."

One barrier to fundamental change on pricing and reimbursement, however, will be the current Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) agreement, which was first launched in 2014 and won't end until December 2018. The agreement guarantees low growth in the medicines budgets and very significant rebates from pharma; the industry has already paid back £1 billion, and the ABPI forecasts that the sector will return £3 billion in rebates over the deal's five-year lifespan. The Department of Health is likely to allow new experimental pricing approaches to be tried out, but almost certainly won't renegotiate another pricing framework for all products before 2018.

The new CDF and an evolving NICE

Also presenting were Nina Pinwill, associate director of NICE's new Office for Market Access, and Professor Peter Clark, chair NHS England Chemotherapy Clinical Reference Group and former chair of the CDF.

The controversial CDF will now be re-launched on 1 July following extensive consultation. Pivotal to the new CDF is that it will be co-managed by NICE and NHS England. Cancer drugs will retain their 'special status', automatically being reviewed by NICE, which will aim to publish a decision on new cancer drugs shortly after a drug receives a recommendation of marketing authorisation from the European Medicines Agency's CHMP committee.

Only a small minority of drugs are expected to be put forward for the CDF, which will be a 'managed access' fund, giving drugs 24 months to prove their value (through maturing clinical trial data or RWE) before a final decision on access is made.

Prof Clark said one of the main messages for pharma was that companies should do all they can to gain a positive decision through the now accelerated initial NICE appraisal.

"First call on any money in specialised care is for NICE-approved drugs. Take the lesson home, folks," he stated.

Asked whether he believed the conditional marketing model being pioneered in cancer could be extended to other disease areas, he was positive it could and should.

"It has to – if this is going to work for cancer drugs, then why can't it work for everything else? I very much hope so."

Alastair Kent, chair of the Genetic Alliance, an umbrella organisation representing 180 rare disease patient groups, also spoke at the meeting. Taking part in an Oxford-style debate on whether 2016-17 would indeed be a 'transformative year' for market access, he eloquently opposed the idea.

Speaking with brutal frankness, he said NHS England was under pressure as never before, and had a 'kick the can down the road' attitude to new medicines, often simply delaying thorny spending and commissioning decisions.

He said this was a mentality that "precludes sustained strategic development that the delivery of improved access will require."

Alastair Kent also condemned the CDF, and said the new version didn't address the fundamental unfairness of putting cancer treatment above all other therapy areas.

While Clark and Barker both spoke persuasively and optimistically in favour of the motion, the assembled pharma executives voted overwhelmingly against it.

The ABPI's Mike Thompson spoke against it, saying it couldn't be a defining year until the NHS received a better level of funding. Nevertheless, he rounded off the debate by urging the UK pharma industry to engage positively with the NHS agenda.

"I believe the AAR is going to provide a flexibility for us that we've never had before," he said. "I know there are some issues – such as uptake of hepatitis C drugs, I think we all understand that. But let's grasp this opportunity, and set our sights on building a UK health powerhouse."

Whether there are really grounds for optimism will be seen in 2016/17 and in the next few years. As the industry pipeline is now regularly producing potential 'breakthrough' medicines, it won't be very long until these good intentions are tested.