The rise and fall of PPRS payments

Leela Barham delves into the Department of Health’s accounts to see how contributions from the updated Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) have affected its budget for the NHS since such payments began in 2014.

The Department of Health (DH) released its latest formal accounts on 19 July 2017. This provides a chance not only to review how the DH has managed its money, but also to see how payments under the 2014 Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) have contributed to its funds.

The numbers

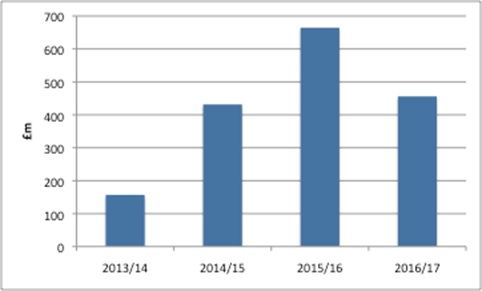

The DH annual report and accounts make it clear that PPRS payments are income for the DH, worth £456 million in the 2016/17 financial year. That adds to the income brought in over the years that the 2014 PPRS payments have been in place (Figure 1). Based on these figures, payments up the end of the 2016/17 financial year were more than £1.7 billion.

Figure 1: DH income from PPRS payments, 2013/14 to 2016/17.

Source: Analysis of DH annual reports and accounts 2013/14, 2014/15, 2015/16 and 2016/17

For the first time, though, the DH accounts also clearly identify the scale of the shortfall when PPRS payments were less than expected by including a variance explicitly in the annual accounts. For 2016/17 the DH expected £584 million but received £456 million, leaving a gap of £128 million.

The narrative

Over time, the DH annual reports and accounts also tell a story of the unpredictability of the PPRS.

The 2014/15 DH annual report and accounts, published in July 2015, represented the first full financial year that included the new-style PPRS payments after the scheme was revamped. Instead of headline price cuts, member companies made PPRS payments to the DH. This report showed the upside of the unpredictability for the DH. The report said, ‘growth in 2014-15 has been higher than initially anticipated, which has resulted in greater voluntary payments being received’.

However, by the time of the 2015/16 DH annual report and accounts there was evidence of the downside. That report pointed out that the DH had given more to NHS England (NHSE) in advance, for the 2015/16 financial year, than it had actually received in PPRS payments. HM Treasury granted the DH £0.2 billion to cover the gap.

Another year on, in the 2016/17 annual report and accounts, the DH recorded lower-than-expected PPRS payments as part of ‘unforeseen pressures of c£0.3 billion [that] emerged during the year, mostly relating to the Prescription Pricing Regulation Scheme (PPRS) and European Economic Area Medical Costs (EEA) budgets’.

The variability of PPRS payments

At the heart of the 2014 PPRS was a move away from headline price cuts to payments that depended on how much higher the spend on branded medicines covered by the 2014 PPRS was going to be, in comparison to that permitted under the allowable growth rate.

In order for everyone to plan ahead, though, forecasts were made. The DH wanted to know how much it would get and then be able to allocate out to the wider NHS. For companies, forecasting would help them set aside payments that would become due. UK affiliates probably used forecasts to help them manage expectations when their HQ might be in the US and far away from the realities of the UK market place.

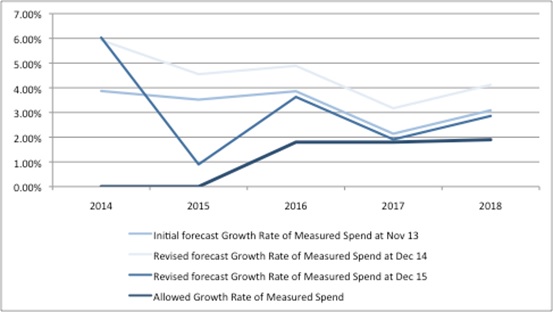

The trouble with forecasts is just that; they are forecasts. Things have changed quite a lot over time, with spend on branded medicines not following the growth expected. The original forecast of measured spend – published in November 2013 – with the benefit of hindsight now seems over-optimistic, as the figures have been downgraded every year since (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Forecast growth rate of measured spend under the 2014 PPRS and allowed growth rate of measured spend over time.

Source: DH data from Nov 13, Dec 14 and Dec 15

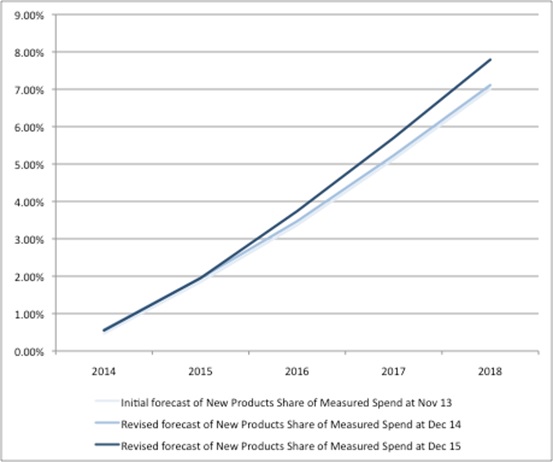

The 2014 PPRS measures spend including new products, but the payments from companies exclude spend on new products. Here, too, things have changed over time, with the forecast share of new products in measured spend rising (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Forecast of share of new products’ share of measured spend over time.

Source: DH data from Nov 13, Dec 14 and Dec 15

In turn, in light of both actual spend and as forecasts have been updated, this has changed the payment percentages expected from companies. Actual payment percentages can only be known incrementally as data on real spend becomes available.

The drivers of unpredictable PPRS payments

The 2015/16 report suggested that the PPRS falling short of expectations was a result of ‘spend not controlled by the PPRS cap … growing at a faster level than controlled spend’. The PPRS doesn’t cover everything. For example, certain tenders are excluded. The PPRS is voluntary and not all companies selling branded medicines are members. The DH noted, too, that parallel imports were growing and that products switched from the PPRS to the alternative statutory scheme for branded medicines. By May 2016 five companies had left the PPRS. Under the statutory scheme, companies didn’t make payments, but took a price cut instead. Since then the legislation has changed.

On top of dynamics in the market that resulted in less-than-expected PPRS payments, was an adjustment related to how to deal with the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF). The DH and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) reached an agreement that some spend under the CDF could be exempt from PPRS payments in order to resolve a dispute; in operational terms that meant adding an amount to the allowed spend. The CDF adjustment added £91 million in 2014, and £107 million in 2015, to allowed spend (calendar years).

The future

The final payment percentages will fall between 2.3% and 7.8% under the current PPRS, which is due to end on 31 December 2018. These payment percentages, in turn, will generate between £320 million and £439 million in PPRS payments.

However, a bigger question than how much PPRS companies will pay is what will replace the 2014 PPRS?

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system, both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com.

Read more from Leela Barham:

Creating headroom: can cutting spend on low-value prescriptions fund new drugs?