Real world cost effectiveness: lessons from the MS risk sharing scheme

Real world cost effectiveness data is in high demand, but how easy is it to find and assess in practice? Leela Barham investigates the pros and cons through an examination of the MS risk sharing scheme, which has been running since 2002.

Interest in real world cost effectiveness – value for money of a product when it's used in everyday practice, not the trial setting – has, arguably, never been higher as budgets are tighter and the art and science of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is more mature.

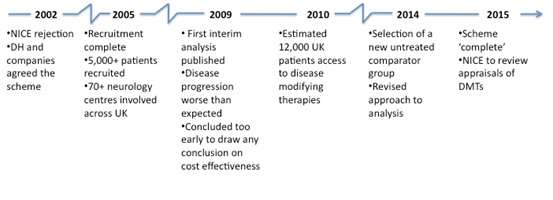

Not only do payers want to know what a product's cost effectiveness is in theory, but also in practice. The UK's multiple sclerosis (MS) risk sharing scheme, which began in 2002 prompted by rejection of disease modifying drugs by the UK health watchdog NICE, presents an ideal case study in exploring cost effectiveness, both in theory and in practice.

The disease

MS is a neurological condition that affects some 100,000 people in the UK. It is an unpredictable disease; people can experience 'relapses' where they lose neurological function then experience complete or incomplete recovery, known as 'remission'. That MS has a major impact on people and their families is without doubt, as people have to cope not only with the loss of function, but also with the emotional impact.

The products

The risk sharing scheme covers National Health Service (NHS) purchases of disease modifying therapies (DMTs) including Biogen's Avonex, Schering's Betaferon, Serono's Rebif (all beta interferons) and Teva's Copaxone (glatiramer acetate). Under the scheme they were made available at costs per patient year ranging from just under £6,000 to the highest at just under £9,000.

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical trials reviewed by NICE as part of the Technology Appraisal 32 (TA32) suggested that the beta interferons and glatiramer acetate could reduce the frequency of relapses and, in some circumstances, that beta interferons might even reduce the severity of those relapses. With only three years' worth of clinical trial data available, it was hard to know the real world benefits over the long term.

Cost effectiveness in theory

NICE looked at cost effectiveness estimates available from the general literature, the manufacturers, and commissioned new analysis. The problem was the huge range in estimates around the world; from £10,000 per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) to over $3 million. As may be expected, the lower figure came from a company, the higher one from an American research group, and numbers in between came from the analysis NICE commissioned from the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR). The ScHARR analysis suggested that the products were not cost effective over a 10- or 15-year time period, but they did become more cost effective over a 20-year time horizon.

The appraisal itself generated a great deal of debate, with concerns raised not only about the evidence and analysis for these specific products, but also about the appropriateness of the general approach, including use of tools like the QALY. Perhaps this was partly because the appraisal started in 2000. This was just a year after NICE was set up, and companies and patient groups were getting used to going through the 'NICE experience'. One has to wonder how far the scheme was as much a reaction to the politics of the day, as much as responding to the specifics of the products.

The scheme

The basis of the scheme was the agreement of the manufacturers to lower their prices if their medicines failed to meet agreed cost effectiveness benchmarks. Prices were reduced at the outset of the scheme too.

The scheme required monitoring of at least 5,000 patients, treated at both existing and new specialist centres, over 10 years. The target was a £36,000 cost per QALY. If this was not met, the manufacturers must cut prices to restore the £36,000 threshold (but if they were better than that, they would not be allowed to charge more).

Manufacturers also contributed to the cost of additional specialist nurses to complement staff available in the NHS, as well as paying towards education and training for those staff.

The governance of the scheme was a little complicated, partly because so many different parties were involved. They included patient groups, NHS clinicians, a contract research organisation (Parexel), the Department of Health and the four companies.

ScHARR was involved for the three-year recruitment phase and coordinated the data collected and proposals for statistical analysis, but decided not to take part in a tender to carry on, citing concerns about data access and publication rights. Instead, Parexel took over data collection and statistical analysis.

Controversy at the outset

The scheme was not universally supported when it came about. Some pointed out that it might have been better to have followed a more traditional route of further randomised controlled trials. Others said that there was no shared risk at all, because of inherent biases in the scheme.

Criticisms have followed over time, too, not least regarding why early analysis available in 2009 did not result in a price cut. Even now, questions are still asked about the scheme in the UK parliament, including whether new products should be included in the scheme.

NICE review

NICE does not have a formal role in the scheme, but it does have a commitment to review its TA. In 2007 NICE checked if the evidence base had changed, and decided then that there was no new evidence available that would affect the original 2002 rejection. Just last year NICE decided to put off review of TA32 until 2015. It will review not only TA32, but also appraisals for newer products to treat MS (TA127 on Natalizumab and TA254 on Fingolimod).

It also highlights how long it can take before any analysis can be undertaken and, even then, that analysis might not be very informative. The challenges in drawing valid conclusions from real world data are significant; specific concerns include the appropriateness of the comparator group, how far assumptions made in the early cost effectiveness modelling followed reality, as many patients improved over time yet the initial modelling didn't allow for this, as well as dealing with bias.

Now, in 2014, much has changed, with a new comparator group, and the development of a new analysis plan.

Lessons

Get as much insight as possible from the existing evidence base

Those involved in the scheme have pointed out that, with hindsight, further analysis of the evidence base at the time that decisions were being made about the products could have 'shed additional light' on the situation. Who knows if this might have changed the scheme, but before incurring the time and money involved in setting up a real world study it is probably a good idea to squeeze every last insight out of existing data.

Keep it simple

The MS scheme is complex. It has been argued that keeping to a smaller sample and a well-defined measure could be markers of more successful risk sharing schemes.

Align local and national commitments

The scheme is a national one but it seems that the NHS has had to be reminded about the legal requirements to fund the products in the scheme – once in 2006 and again in 2011. So ensure that the local parties are reminded of what they need to do.

Plan to change your plans

The scheme has had to change in light of experience. Perhaps some of this could have been avoided, but maybe not, so it is probably best to be a little flexible. As they say, it may be better to be roughly right, than precisely wrong.

Clarify governance

There have been concerns raised about the governance of the MS scheme, particularly regarding vested interests. Getting the right balance of transparency and expertise, when some of that might need to come from those who have a vested interest, is likely to be tricky. But it is also likely to be time well spent.

Draw on experience and review good practice

While the MS scheme was ground-breaking at the time of its inception, anyone thinking of using one now can draw on much greater experience. There are good practices out there.

Too early to measure success

The scheme has delivered benefits; often cited is the fact that it has enabled patients to access drugs that they might not otherwise have had. But, even now, concerns remain that not all patients are getting DMTs. In fact, estimates suggest that just 40 per cent of eligible UK patients actually receive them. Other benefits include the additional MS nurses, a network of clinicians/centres and a new understanding of the disease.

However, the scheme has come at considerable cost. Estimates suggest that the monitoring scheme has cost around 1 per cent of the costs to the NHS of the products. Some have put the real cost of running the scheme at around £50 million a year – and of course a lot of time has been spent by clinicians collating the data across 72 centres. Then there are other cost consequences too, like NICE approving the newer, and much more expensive, Natalizumab, because the standard of care, and hence the comparator for Natalizumab, are the same products that NICE was so uncertain about before.

It is hard to know now if it has all been worth it. We should know more when the scheme is 'complete' in 2015.

About the author:

Leela Barham is an independent health economist and policy expert who has worked with all stakeholders across the health care system both in the UK and internationally. Leela works on a variety of issues: from the health and wellbeing of NHS staff to pricing and reimbursement of medicines and policies such as the Cancer Drugs Fund and Patient Access Schemes. Find out more here and you can contact Leela on leels@btinternet.com

Have your say: What is the true value of real world data?